The Hyde Amendment is back.

From holding up Loretta Lynch’s confirmation as Attorney General and a bill to help victims of sex trafficking to threatening to blow up a carefully calibrated bipartisan agreement on a number of important health policy fixes, it seems there’s no end to the trouble caused by this amendment from hell.

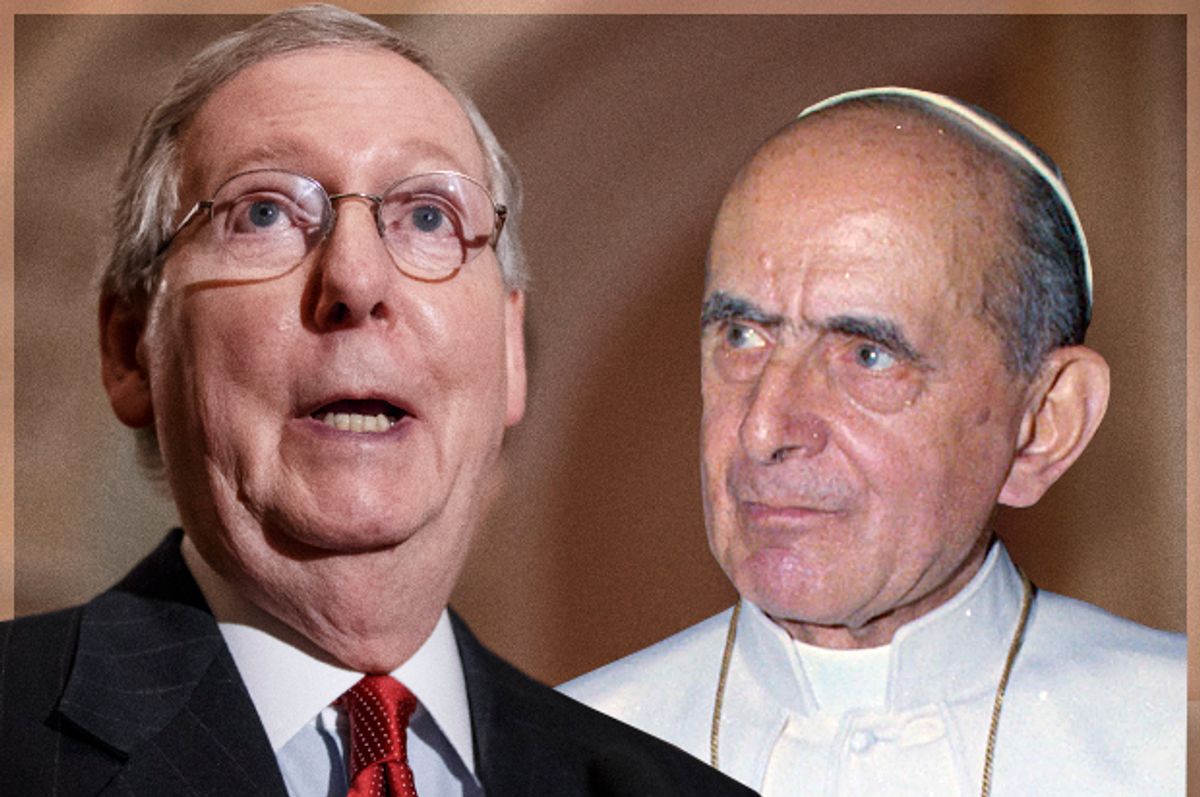

It’s no secret that the Hyde Amendment -- to ban federal funding of abortions for low-income women in the Medicaid program -- was introduced by pro-life Catholic Congressman Henry Hyde in the mid-1970s and has plagued appropriations bills ever since. But what’s not as well known is the backstage role that the Catholic Church played in its creation.

In fact, without the church, there might not be a Hyde Amendment.

Henry Hyde was a first-term congressman from Illinois when he introduced the amendment in June of 1976. The fledgling anti-abortion movement had been trying desperately since Roe v. Wade three years earlier to get Congress to pass a “Human Life Amendment” to ban abortion, but wasn’t getting anywhere.

The amendment took everyone by surprise, and represented a whole new tactic. Instead of banning abortion outright, opponents would seek to chip away at access by any means available. As Hyde himself famously said:

“I certainly would like to prevent, if I could legally, anybody having an abortion, a rich woman, a middle-class woman, or a poor woman. Unfortunately, the only vehicle available is the … Medicaid bill.”

The bill passed the House but ran into opposition in the Senate. But with elections looming and abortion already a contentious issue in the presidential race, neither chamber of Congress wanted a drawn-out fight. So the Senate acquiesced—with an exception if a women’s life was in danger—because it expected the Supreme Court to strike down the Medicaid funding restriction in two pending state cases.

But when the Supreme Court upheld the restrictions and Hyde reintroduced the amendment in 1977, an epic six-month battle broke out that paralyzed Congress. The Senate dug in and sought to lessen the impact of the ban by allowing “medically necessary” abortions, as well as abortions for rape and incest. Leading the charge for the most restrictive form of the amendment -- with no exemptions whatsoever -- was Mark Gallagher, the lobbyist for the National Committee for a Human Life Amendment.

The NCHLA was created in 1974 by the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops after it lost control of the National Right to Life Committee, which it also created, to a group of Catholic and Protestant anti-abortion leaders who were concerned that the bishops’ involvement hampered anti-abortion efforts. The National Right to Life Committee had attracted millions of members since Roe, but it didn’t have any lobbying clout on the Hill. The NCHLA was the only national anti-abortion organization that “possessed demonstrable political power and expertise,” said Frederick Jaffe, Barbara Lindheim and Philip Lee in their book "Abortion Politics."

Gallagher and Hyde worked hand-in-glove during the negotiations. The New York Times reported that Gallagher “[made] his unofficial home on Capitol Hill in the office of Representative Henry Hyde” from June to December 1977, when there were 25 roll-call votes on the Hyde Amendment. “Innumerable sessions were held by conferees representing the two houses, and endless hours were consumed with arguments over the relative merits of terms like ‘serious’ versus ‘severe’ … and ‘forced rape’ versus ‘rape’,” notes "Abortion Politics."

All eyes were on Gallagher. “Every time the Senate conferees make a compromise offer, Mr. Gallagher quietly walks to the conference table to tell a staff aid to the 11 House conferees whether the proposal is acceptable to the bishops. His recommendations invariably are followed,” the New York Times reported, noting that eight of the 11 House conferees were Catholic.

Although the NCHLA was supposedly independent from the bishops, tax filings show that the organization received nearly half of the $900,000 it raised between January 1976 and March 1977 from the bishops and the other half from dioceses that had taken up collections on behalf of the church’s anti-abortion activism. Parishioners at churches like Our Lady of Mercy in Potomac, MD, received envelopes at mass for special contributions to the Pro-Life Congressional District Action Committee. “[N]ever before has one church, under orders from its leadership, financed a political campaign to the extent of half its funds,” abortion rights pioneer Lawrence Lader wrote in the New York Times.

The bishops’ conference also exhorted Catholics to lobby their representatives against any liberalization of the amendment. The year before, the Catholic bishops had rolled out the Pastoral Plan for Pro-Life Activities, which called for the creation of congressional-level “pro-life units” across the country that the bishops activated to lobby for Hyde. A coalition of small, poorly funded pro-choice groups were no match for the organizational clout of the Catholic Church.

In the end, the lobbying clout of the church held sway. The Senate agreed to an amendment that made exceptions only for the life of a woman, health conditions where two doctors certified that the woman faced “severe and long-lasting” damage, and in cases of rape and incest that were reported to law enforcement authorities. Eventually the limited health exemption was removed as were the reporting requirement for rape and incest, creating the modern form of the Hyde Amendment.

The effects on poor women were devastating. Some 300,000 women a year were receiving Medicaid-funded abortion before Hyde. Studies estimate that up to one-third of low-income women who wanted an abortion have been forced to continue their pregnancies as a result of Hyde and many more have faced financial difficulties or delayed abortion as a result.

Just as importantly, the technique that Hyde and the Catholic bishops pioneered—using health insurance to limit access to reproductive health services—resurfaced 20 years later, as the Catholic bishops and conservative allies pushed for more and more Hyde-like exemptions on everything from the federal employees health insurance program, to abortions for women in the military, to the Affordable Care Act.

But the defeat by Hyde also force the pro-choice movement to grow up and become professionalized. Funding poured in the wake of Hyde and later efforts during the Reagan years to ban abortion. Today, faith-based pro-choice groups, as well as the larger reproductive health and justice community, are working to undue the damage done by Hyde. “As a Catholic, of all the pieces of anti-choice legislation, the one I feel strongest about is the Hyde Amendment,” says Jon O’Brien, president of Catholics for Choice. “The preferential option for the poor is essential to our faith and the Hyde Amendment is meant to hurt the poor. The rich can always circumvent restrictions but it's the poor who suffer. This makes the Hyde Amendment profoundly unjust.”

And it’s not just anti-choice Republicans who need to be held accountable, says O’Brien. “Hyde expires every year, but out of fear of upsetting conservatives, President Obama doesn’t have the courage or conviction to strike it down. Even doing so symbolically would be important to standing up for the poor.”

Shares