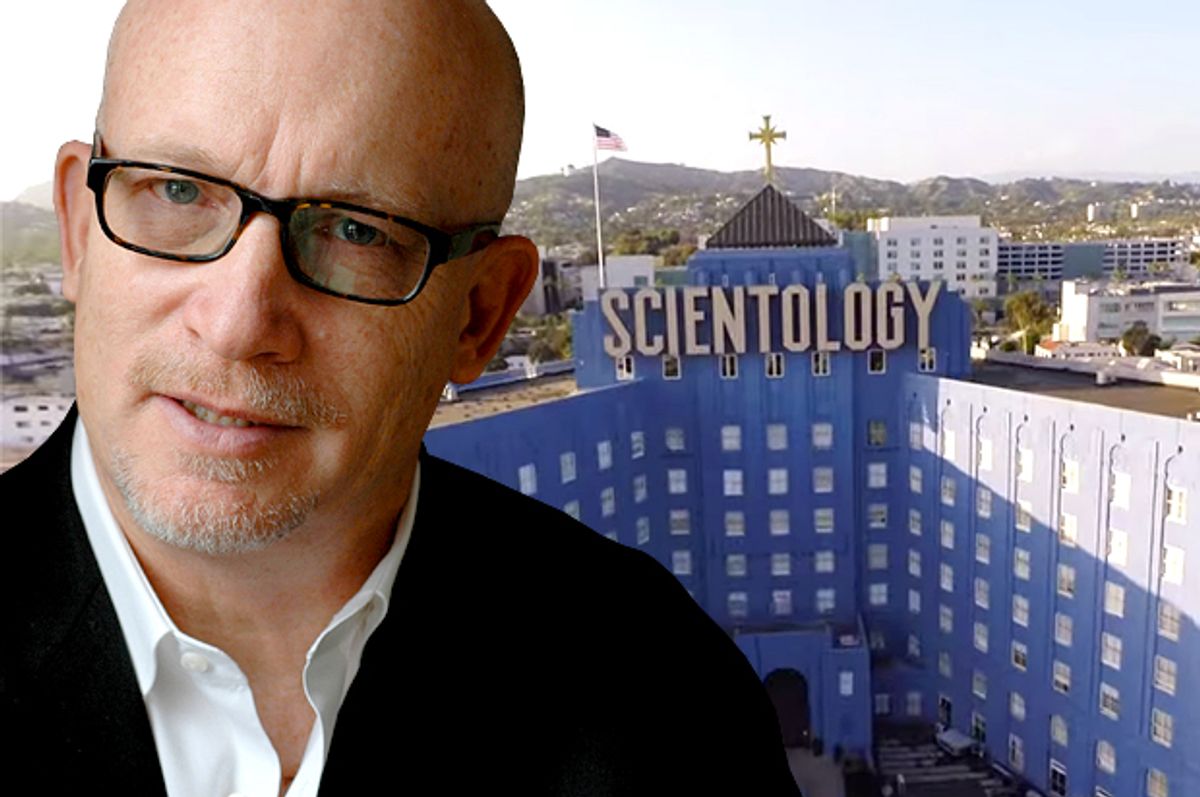

People were shocked by the revelations in "Going Clear," Alex Gibney's expose about the Church of Scientology that aired on HBO last night. But when it comes to allegations of Scientology's crimes and abuses, the film is really just the tip of the iceberg. Lawrence Wright -- who wrote the book on which the film is based -- uncovered so much dirt on the Church that it was impossible for Gibney to include every point of interest in a two-hour film. Here are five more stunning segments from Wright's book (and then go and read the incredible book for yourself).

The disappearance of Shelly Miscavige:

The film paints Church leader David Miscavige as an abusive, violent, power-hungry autocrat; however, it omits the chilling detail that "COB"'s wife, Shelly, hasn't been seen in public since 2007. According to Wright, a number of ex-Sea Org members believe she is being guarded at a California Church facility. (In 2012, Shelly’s attorneys said that “any reports that she is missing are false. Mrs. Miscavige has been working nonstop in the Church, as she always has.”) For more interesting details, read Vanity Fair's 2004 profile, titled "Scientology's Missing Queen."

The harassment of Paulette Cooper:

The film depicts the scope of Scientology’s litigiousness and its campaigns against its critics, particularly Mike Rinder’s harassment of BBC reporter John Sweeney. But it doesn’t go into detail about the harrowing case of Paulette Cooper, a journalist who published “The Scandal of Scientology” in 1971. Wright's book includes an account of the Church's so-called Operation Freakout, which was reportedly designed to “get Cooper incarcerated in a mental institution or jail” after her book came out. And indeed, Cooper’s personal and professional life were turned inside out. As Wright writes, “She was followed; her phone was tapped; she was sued nineteen times.” Cooper was even indicted for making bomb threats against the Church as well as for perjuring herself, although the case was eventually dropped.

The death of Lisa McPherson:

Wright goes into detail about the horrific case of Lisa McPherson, who died in the Church’s care after suffering a mental breakdown. Because McPherson had recently been declared “Clear,” her breakdown was potentially damaging for the Church; their response was to seclude her for 17 days in a Florida hotel to undergo a Scientology procedure known as the “Introspection Rundown.” Per Wright: "Instead of calming down, McPherson stopped eating. She screamed, she clawed her attendants, she spoke in gibberish, she fouled herself, she banged her head against the wall. Staff members strapped her down and tried to feed her with a turkey baster. On December 5, McPherson slipped into a coma.” Then, instead of taking her to the nearest hospital, Wright claims that Church operatives drove her to a hospital much further away that housed a doctor affiliated with the Church. By the time they got there, she was dead.

McPherson's death kicked off an investigation and lawsuit that lasted for five years, and created a P.R. nightmare for the Church. Says Wright: “In the eyes of the world press, Scientology had murdered Lisa McPherson. She was one of nine Scientologists who had died under mysterious circumstances at the Clearwater facility.”

Miscavige’s lavish life:

You got a sense of it in the film, but Wright's book paints a stark contrast between the leader’s lavish life and the poverty of the Church’s members. As Wright illustrates, Miscavige’s daily dinner is a five-course meal with the choice between two entrees. As Wright says: “Miscavige’s favorite foods include wild mushroom risotto, linguine in white clam sauce, and pate de foie gras. Fresh fruit and vegetables are purchased from local markets or shipped in from overseas. Several times a week, a truck from Santa Monica brings Atlantic salmon, or live lobster, flown in fresh from the East Coast or Canada. Corn-fed lamb arrives from New Zealand….Two full-time chefs work all day preparing these meals, with several full-time stewards to serve them.”

The details continue, with Wright describing Miscavige's $20,000 per week food costs -- an estimation that includes his (now-vanished) wife and guests -- as well as his $150,000 stereo system, his personal tanning bed and high-end gym, his six motorcycles, his armor-plated GMC Safari with bulletproof windows and satellite television, his shoes, which are custom-made by the royal family’s shoemaker in London, the private Boeing business jet on which he travels, and on and on.

The final showdown:

Wright’s book concludes with him and his team at the New Yorker going head to head in a conference room with the Church’s lawyers as they fact-check Wright's Paul Haggis profile. It’s a remarkable showdown, which illustrates just how challenging it must have been to produce the book and film, given the Church's constant scrutiny and aggressive litigiousness. The chapter also sees a ballsy Wright challenging the Church on points of doctrine; an especially revealing moment takes place when former Church spokesman Tommy Davis acknowledges that if it is true that Hubbard was never actually injured during the war, then "Scientology is based on a lie." Of course, Wright is able to prove pretty conclusively that the records of Hubbard's injuries are invalid. As he puts it: "I believe everyone on the New Yorker side of the table was taken aback by this daring equation, one that seemed not only fair but testable."

Like we said: Go out and read the book!

Shares