By now, it’s clear that Indiana’s Religious Freedom Restoration Act was crafted to empower piously bigoted entrepreneurs and companies desirous of freelancing with their own “Jim Crow for gays” restrictions, and to let them cite as legal justification for doing so their precious religious sensibilities. The RFRA, said the original text, sought to give judicial succor to those who found that their “exercise of religion . . . has been substantially burdened,” or was just “likely to be substantially burdened” by performing services for people their faith’s sacred credos enjoin them to abhor (gays, in this case). The ensuing uproar in the media and business circles compelled Indiana’s state Senate to amend the legislation to prevent its deployment against the LBGT community, but state Democrats are still calling for its repeal.

The danger, however, has by no means passed. RFRAs already exist in 21 other states (in three of which, bills are pending to fortify them), and three more are considering adopting similar measures. The RFRA just passed last week in Arkansas may allow faith-based discrimination; we now await a test case.

Yet the real menace to our priceless heritage of secular governance comes from the Supreme Court, which a year ago (in Sebelius v. Hobby Lobby) ruled that corporations, on the basis of their religious convictions (yes, the Court decided corporations have those), can exempt themselves from the Affordable Care Act’s relevant articles and refuse to pay for contraceptives in their employee health plans. (Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, in her dissent, warned that this was a “decision of startling breadth,” and she was right.) If a case involving a new manifestation of such legislation (say, the Arkansan RFRA) ever lands before the nine-member Roberts Court, its five conservative justices will no doubt adjudicate in favor of the faithful – and against rationalists who hold that religion, in no shape or form, should be allowed to infect our legal system. What is really needed is a federal LGBT shield law, but none exists.

RFRAs don’t define religion or specify to which religion they pertain. But a lot hinges on how we define religion. Everyone knows what dictionaries say it is. We’re also all too familiar with another definition, one by which faith is an entirely spiritual affair, a matter of transcendental, miraculously elastic interpretation never to be held accountable for the witless antics, casual brutality and gross atrocities committed by its practitioners. (Reza Aslan is the most prominent advocate of this view.) Both definitions lend an aura of dignity and gravitas to what is essentially sordid gibberish that we should dismiss out of hand, as we now do necromancy, phrenology or alchemy, or simply laugh off.

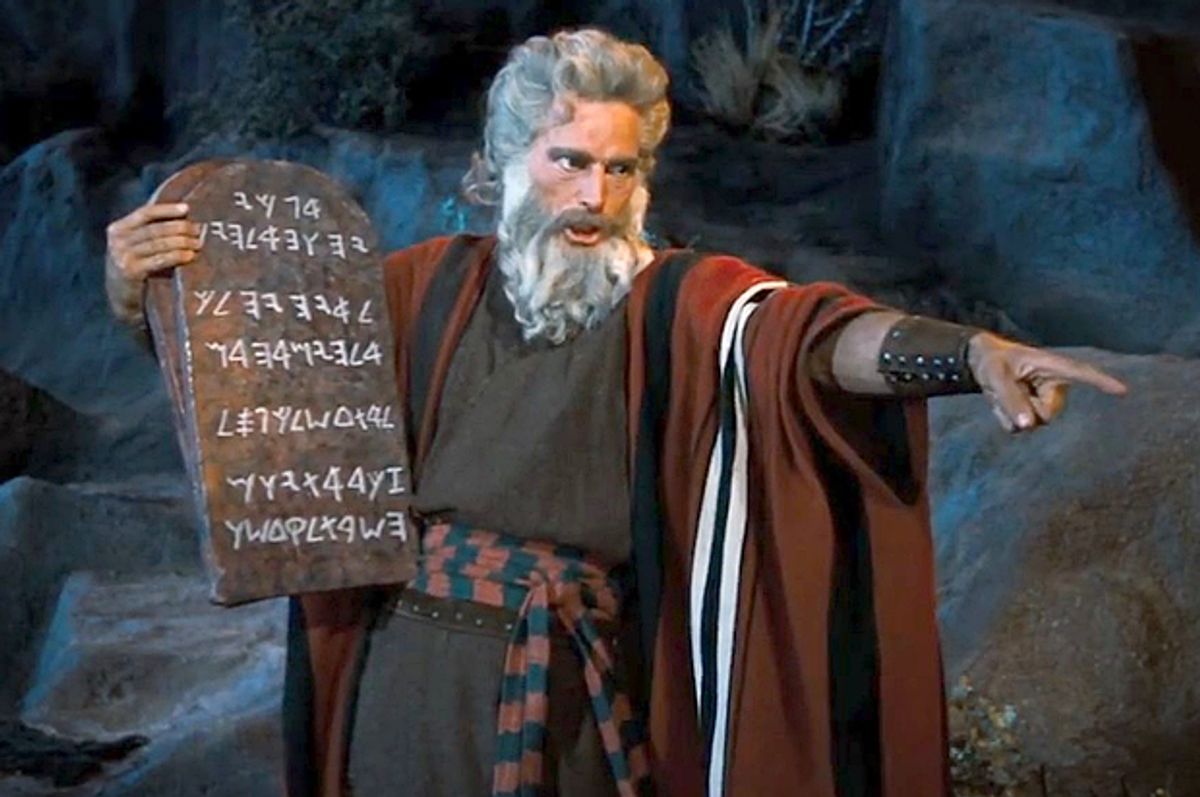

Yet religion is far too dangerous to our liberties to be laughed off or mischaracterized as harmless. In its Abrahamic strain, it is a triad of antiquated, largely pernicious ideologies of control and exclusion suffusing various “holy” books that detail a phony cosmogony, a fairy-tale version of humankind’s origins, and a plethora of strictures meant to regulate and restrict our behavior. This “sacred” canon glorifies the (frequently) vile misdeeds and plodding pontifications of a wide range of characters, among whom occur prophets and patriarchs (some of whom are felonious, even murderous, miscreants) and their hapless victims (mostly women, girls, infants, foreigners, and “unbelievers”). A fictitious celestial tyrant superintends the almost ceaseless slaughter playing out in the Bronze-Age phantasmagoria of his alleged creation. He periodically issues injunctions to his wayward subjects, and punishes them cruelly when they fail to obey (or just for the heck of it, as one righteous resident of the Land of Uz discovers). Though these ideologies purport to embrace humanity as a whole, the phantasmagoria’s action takes place in a dusty, too-hot corner of the Mediterranean, parts of which once had the honor of hosting the Greeks and their Hellenic culture, the Romans with their laws and roads, and of course the haunting civilization of ancient Egypt.

How do today’s subjects of this fictitious tyrant know what his commands are? The supposedly infallible despot made the mistake of issuing his rule books in ancient tongues that most (including a majority of Hoosiers and Arkansans, we can safely say) cannot read in the original. This compels his subjects to muddle along with translations, which vary considerably, at times critically and confusingly. Nevertheless, most of his subjects profess to understand his words with exactitude, and accord them incantatory, magic powers. In times of distress and duress, they utter their magic words, heads bowed meekly or turned imploringly heavenward, hoping to conjure up the fictitious tyrant’s goodwill, or prompt him to grant special dispensation.

His pronouncements are regarded as binding on all humans. Hence, if the fictitious tyrant says, for instance, that gay sex is an abomination, it just is, and gays have to be abominated, like it or not. Nothing personal – it’s just what the magic book says.

True devotees of these magic books see no need to think for themselves, because their books, being magic, have answers for literally everything. Sort of like a single pill that could cure every disease on earth, from the common cold to brain cancer, from chicken pox to the bubonic plague. Strangely enough, though, unknown humans came up with these magic books in a time before people knew what germs were, what gravity was, or that the earth orbited the sun, or that the earth was round. But the magic books, because they are magic, have to be believed. Why? Because the magic books say so.

Failure to believe in said magic books is a great sin. Why? So the magic books themselves decree. According to one of the magic books, those who announce they’ve stopped believing in it deserve to die. Hoosiers who believe in their particular magic book can’t issue death sentences of that sort (yet), but the original version of their RFRA would have allowed them to mistreat anyone their fictitious tyrant doesn’t like, in accordance with what’s written in their magic book, and with the backing of courts of law. Talking about “magic books” and “courts of law” in the same breath seems strange, because it is strange. Which of the two phrases doesn’t befit our day and age?

If RFRAs are passed that permit entrepreneurs to discriminate against LBGT people, what would this look like? This is worth imagining, at least as long as there’s no federal LBGT shield law. So, a couple consisting of two award-winning, well-mannered gay molecular biologists arrive at a restaurant in the South or the Midwest. They are to deliver lectures of momentous scientific import at a local university, but they are told to get up and clear out by a restaurateur ranting about what’s in his magic book. If they sue him, he could, in court, avail himself of protection afforded by his state’s RFRA and cite the verse from his magic book as his justification.

How would this restaurateur prove to a judge that he actually believes what’s written in his magic book? After all, most of it is pretty crazy stuff – talking snakes, burning bushes, suns standing still, virgin births, walking dead folk, and so on. A lawyer for the gay plaintiffs might challenge the restaurateur to present concrete evidence that he really does believe, and so has truly been “burdened.” For instance, has he had the elders of his town stone any of his children to death recently for disobedience, as Deuteronomy 21:18-21 requires? Has he killed any false prophets lately, as Zechariah 13:3 ordains? And does he eschew rabbit meat? The fictitious tyrant forbids it, since, says Deuteronomy 14:7, rabbits “chew the cud,” yet “part not the hoof.” Does the restaurateur actually understand the fictitious tyrant’s “reasoning” here? If he does, paradoxically, that may constitute ample grounds for the judge to declare him of unsound mind, though whether he would then rule in favor of the plaintiffs is unclear.

Let’s take another example. A male atheist runs a hotel in the South or the Midwest. An attractive young male-female couple approaches him at the reception desk and asks for a room. The nonbelieving hotelier finds the woman extremely hot, and suddenly burns with jealousy that her companion is about to enjoy her intimate company in one of his establishment’s rooms. To spoil his day, the hotelier can demand a marriage certificate, and deny them accommodation when they fail to produce one, saying it “burdens” his religion to rent rooms to “fornicators.” The couple sues, and their attorneys unearth past evidence of the hotelier’s atheism. But how can they prove what he believed at the moment the couple crossed his hotel’s threshold? Perhaps he had just seen the light and converted. Hail the Lord!

Given that RFRAs don’t specify to which religion they pertain, if they do legalize discrimination, they will do so ecumenically, offering adherents of all denominations a chance to bully both rationalists and believers of other cults. Presumably followers of the Torah, say, could deny service to those who have performed any of thirty-nine types of activity forbidden on the Sabbath. If so, beware -- these include some pretty improbable things, like putting out fires, writing one’s name and erasing it, flaying a goat and separating threads. Especial woe to gays performing these things on the wrong day of the week! Jews and Christians might wish to unite in denying service to Muslims, because, obviously, neither of their magic books recognizes the Islamic magic book. But such an inter-faith alliance would be short-lived. How long would it be before Christians revive the age-old charge of deicide against the Jews and halt all service to the “murderers of Christ?”

Muslims, in turn, could deny service to Jews and Christians for having rejected the Prophet Muhammad. However, they might actually have a harder time proving their case in court because Islam recognizes Jews and Christians as ahl al-kitab – “people of the book” -- that is, as their predecessors in honoring the same fictitious tyrant, and thus deserving of some respect.

The three Abrahamic faiths aren’t the only faiths around, of course. What about ancient Greek religion? If a discriminatory RFRA comes into effect in your area, why not worship Dionysus, the god of fertility and wine? You can imagine the sort of obligatory activities this god would demand of you. You could deny service to those who burden your religion by declining to share your wine or bed. And what about worshipping Aphrodite, the goddess of love and beauty? Why not profess yourself to be her votary, and refuse service to obese Evangelical dullards or Mormons with their ugly underwear? And what about scientologists? Shouldn’t they be able to deny service to anyone caught repudiating their inner thetan? United States law, after all, recognizes scientology as a religion on a par with Judaism, Christianity and Islam, which says a lot. For more information, see under “undeserved respect.”

And why be Eurocentric? Hindus may wish to deny service to Christians, who generally drink alcohol and eat meat, which Hinduism forbids. Followers of Rati, the Hindu goddess of love and lust, might refuse service to the unlovable and un-lust-worthy. And so on.

Or maybe those in states with discriminatory RFRAs would prefer to tailor their bigotry and hop from faith to faith, depending on the people of the day they’d like to deny service to. Nothing stops a person from being a Christian today, a Jew tomorrow, a votary of Rati the day after. If you believe in one magic book, switching to another should pose no problem. What you rarely find these days is an atheist converting to a religion. Once you see the light, your eyes have a tough time adjusting to the dark.

Such are the farcical dilemmas and rank absurdities with which religion threatens to swamp us if it infests our judicial system and trumps secular law, as any RFRA legalizing faith-based discrimination would do. The ghastly morass to which RFRAs will one day probably lead speaks to nothing but the ahistorical ignorance of their drafters. The Founding Fathers never meant for religion to play a role in our affairs of state. If the First Amendment isn’t proof enough of this, doubters might check out other things they wrote.

James Madison declared that “An alliance or coalition between Government and religion cannot be too carefully guarded against,” and thought that “Ecclesiastical establishments tend to great ignorance and corruption, all of which facilitate the execution of mischievous projects.”

John Adams authored a treaty, signed by none other than George Washington, proclaiming that the United States was "not in any sense founded on the Christian religion."

Thomas Jefferson, a key figure of the Enlightenment and the author of the “wall of separation between church and state,” had this un-Christian prediction to proffer about Christianity: “the day will come when the mystical generation of Jesus, by the supreme being as his father in the womb of a virgin will be classed with the fable of the generation of Minerva in the brain of Jupiter.“ The Book of Revelation he dismissed as “merely the ravings of a maniac, no more worthy nor capable of explanation than the incoherences of our own nightly dreams.”

These days, sadly, with the godly on the legislative march, and the Roberts Court sitting in Washington ready to back them up, we find ourselves facing an unprecedented threat to what remains of our democracy.

Would religious folk, if they succeed in passing laws that empower them to use their faith as a bludgeon, prove restrained in invoking them? After all, Indiana’s governor had his state’s RFRA amended.

Maybe, but don’t count on it.

Shares