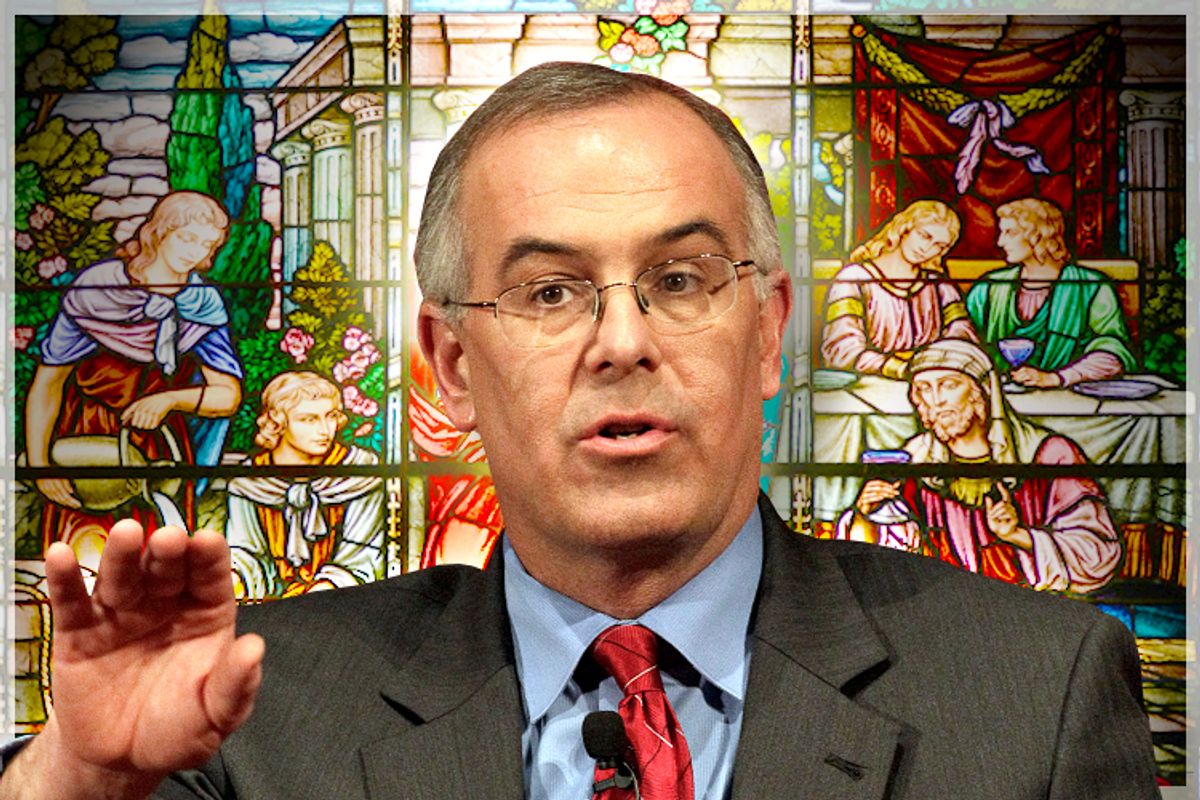

This week, proponents of today’s “religious freedom” acts in Indiana and Arkansas seemed bewildered by the harsh national backlash against them. But for anyone who seriously believes (to cite New York Times columnist David Brooks’ example) that allowing an evangelical wedding-cake baker to refuse to bake for a same-sex couple will strengthen evangelical Christianity, the lesson from America’s Constitutional history of religious freedom is this: be careful what you wish for. They might just weaken religion instead.

In 1783, James Madison was back in Virginia from a three-year term in Congress, and serving as a delegate in the General Assembly. Then, as now, Christian churches were worried they were under threat, with their numbers dropping dramatically during the Revolutionary War.

Virginia’s canny and opportunistic former governor, the Revolutionary hero Patrick Henry, saw a ripe political issue in the churches’ collapse. He proposed a new tax that would fund Christian churches. Madison was appalled by the breach of the church-state wall, and resolved to fight. He jotted down an outline of attacks on the tax, which he delivered, first in a speech, then in a letter several months later.

In a sweeping series of assaults, he charged that states had fallen precisely where church and state were mixed. He challenged Henry’s assumption that moral decay was caused by the collapse in religious institutions; “war and bad laws,” he said, were instead at fault.

He declared that religion belonged to the realm of conscience, not government. Men, considering only the evidence “contemplated by their own minds,” could not be forced to follow the dictates of other men. Religion therefore was unreachable by politics, by the state. In other words, the statecould not support religion, because religion’s strength depends on men’s minds, reason, and conscience.

Madison’s letter sparked a petition drive that ultimately generated over 10,000 signatures, swamping Henry’s bill. Madison’s speech against Patrick Henry’s religious tax went on to become his Memorial and Remonstrance against Religious Assessments, perhaps the Western world’s most famous declaration of the doctrine of the separation of church and state.

His approach to true religious freedom went back to an instance of real religious intolerance, which today’s supporters of religious freedom should look at for a contrast with their own political posturing.

As a recent college graduate back home in Virginia, the Father of our Constitution, James Madison, learned that a sect of Baptists had been imprisoned in nearby Culpeper for preaching without a license. Their captors were giving them only dry crusts of rye bread and water. One tormentor stood on a stool and urinated into the cell.

Madison was infuriated. “Religious bondage shackles and debilitates the mind,” he wrote a college friend, for every “noble enterprize” and every “expanded prospect.” Everywhere he went, he “squabbled and scolded abused and ridiculed” the shameful action. When the Baptists were freed, Madison rejoiced. He later recalled that his activism was “a mere duty prescribed by conscience.”

That word—“conscience”—is the key to understanding the difference between our Constitution’s idea of religious freedom and the one being proposed today. Madison’s theory was based on bolstering private space for religious conduct, prohibiting any government establishment of religion, and always strengthening the wall between church and state—not taking government action to favor one religion’s choices.

What is a conscience? We think about Jiminy Cricket, but according to Merriam-Webster’s Dictionary, a conscience actually lives within our own heart and mind. It’s the “sense or consciousness of the moral goodness or blameworthiness of one's own conduct, intentions, or character together with a feeling of obligation to do right or be good.” The ancient root is the same as for “science”—to be conscious, to know. A conscience, in other words, is intrinsically personal and private.

Madison always fought to ground a public system of religious freedom on that private footing. Eight years before the Baptists were imprisoned, at Virginia’s independence convention of May of 1776, George Mason had introduced a measure that stated “all men should enjoy the fullest toleration in the exercise of religion, &c.” Madison stood and proposed a subtle but monumental change. All men, Madison said, should instead be “equally entitled to the full and free exercise” of religion, “according to the dictates of conscience.”

In Mason’s draft, an individual would be forced to plead with his government for “toleration.” But Madison’s extraordinary new idea was that an individual’s conscience entitled him to a new political right to the full and free exercise of religion. That made private conviction the force within politics. The delegates were swayed by Madison’s amendment, which emerged, over a decade later, in the First Amendment in his Bill of Rights to the Constitution: “Congress shall make no law respecting the establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof.”

That’s the law. That’s the answer. Defenders of religious freedom should stick to it, and work to strengthen faith in its natural home: our individual hearts and minds.

Shares