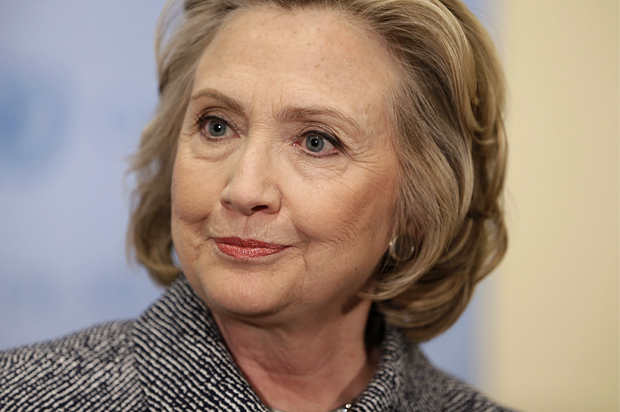

It’s makeover time on the nascent Hillary Clinton for President campaign.

The New York Times reported recently that Clinton has hired a former aide to First Lady Michelle Obama, Kristina Schake, to help freshen up her image. After more than two decades on the national stage, the Times reported, “Mrs. Clinton must try to show voters a self-effacing, warm and funny side that her friends say reflects who she really is. In short, she must counteract an impression that she is just ‘likeable enough,’ as [then Sen. Barack] Obama famously quipped in 2008.”

Although someone close to Clinton told the Times’ reporter that Clinton has no need for a “life coach,” it’s obvious that Clinton, like any candidate, must consider her image as she begins formally running for president.

As another New York Times’ reporter noted, the future candidate “has been exposed to the full view of the American electorate in one capacity or another for some 20 years now, but the politicians, no less than the voters, are still having trouble disengaging his intertwined assets and liabilities.” In fact, that was an observation from a February 1967 Times story about Richard Nixon, the then-former vice president who had lost the 1960 presidential campaign to John F. Kennedy and was plotting his political comeback.

It’s striking how much Nixon and Clinton have in common. They spent years in the shadows of more popular, charismatic politicians (Dwight Eisenhower and Bill Clinton/Obama). They both lost their first presidential campaigns to younger, more charismatic challengers. Their images, as they began their second White House bids, were indelibly etched in the public’s mind.

Nixon was the shady, press-averse loser – “Tricky Dick” – who followed up his 1960 presidential defeat with a humiliating loss in the 1962 California governor’s race. He was so thoroughly crushed by Pat Brown – father of current California Gov. Jerry Brown – that he left the stage with this bitter farewell to a press corps he despised, “You don’t have Nixon to kick around any more, because, gentlemen, this is my last press conference.”

Clinton hasn’t had nearly the rough ride that Nixon endured in the early 1960s, but her life of late hasn’t been a garden party. Like Nixon, there’s her troubled relationship with the press. There is the endless congressional inquiry into Benghazi. Questions persist about the propriety of foreign contributions to the Clinton Foundation during her time as Obama’s secretary of state. And there’s the most recent flair up of bad press over Clinton’s use of a private email account to conduct official State Department business. That’s just in the past two years. Long before losing to Obama, Clinton endured various scandals and humiliations as First Lady.

Now, just as the baggage-laden Nixon had to reintroduce himself to the American electorate, so must Clinton. As Schake begins the task of re-packing the former first lady/senator/secretary of state to the public, she would be wise to study how Nixon’s advisors sold their well-worn candidate to the American people in 1967-68.

For that, there may be no better resource than the late Joe McGinniss’ “The Selling of the President,” the classic 1969 study of the Nixon image machine. Inexplicably, Nixon’s aides gave the young Philadelphia journalist unprecedented access to the media strategy of a presidential campaign. For months, McGinniss quietly sat in a corner and observed as Nixon’s image consultants – among them budding media consultant Roger Ailes – crafted what some observers called “the New Nixon.”

As McGinniss documented, it wasn’t a new Nixon at all. Changing a grown person’s personality in front of millions of viewers would have been be foolish, if not impossible. “It’s not the man we have to change, but rather the received impression,” Nixon advisor Ray Price wrote in one of dozens of fascinating internal memos McGinniss included in his book’s appendix. “And this impression often depends on the medium and its use than it does the candidate itself.”

The ultimate brilliance of the Nixon campaign was a simple but stunning insight, offered by an aspiring advisor, William Gavin, which eventually found its way into virtually every image of Nixon presented to the public: “Instead of the medium using you, you would be using the medium.” In other words, don’t try to twist Nixon into something he is not. Let us assess his strengths and highlight those at every opportunity.

Instead of adapting Nixon to the camera, Nixon’s advisors adapted the camera to Nixon. “So there would not have to be a ‘new Nixon,” McGinnis observed. “Simply a new approach to television.”

Among the events that Nixon’s media team staged were a series of live, televised forums devised by Ailes – the precursor to today’s campaign town hall meetings – during which Nixon answered questions from a panel of average citizens. While the studio audience was carefully selected, the questions were unknown to Nixon in advance. The results were impressive. Nixon was spontaneous and every much in his element, literally the “man in the arena.” He showed the public not that he was right on the issues, but rather, as one aide wrote, that he was candidate “best equipped to deal with them.”

Nixon’s people were obsessed with the idea of “received impression.” In other words, as pollster Frank Luntz is fond of saying, “It’s not what you say, it’s what people hear.”

“[R]eason pushes the viewer back, it assaults him, it demands that he agree or disagree,” advisor Gavin wrote in a memo, adding, “impression can envelope him, invite him in.” What Gavin and others wanted from voters was not an intellectual agreement with Nixon on the issues, but an emotional response. “[G]et the voters to like the guy,” he wrote, “and the battle’s two thirds won.”

The process fascinated McGinniss, who began the book’s second chapter with this undeniably true observation: “Politics, in a sense, has always been a con game.” One might argue, in fact, that the Nixon campaign was the ultimate con game – selling the American people a deeply flawed candidate whose character defects would eventually morph into criminal activity.

But the fact remains that Nixon’s advisors understood something fundamental about politics that many candidates forget or overlook in their pursuit of victory: Voters are not always reasonable beings. Their votes are often based on emotion and impression, not rational thought.

As Ray Price argued, electing a president “is an act of faith.” And that faith, Price correctly observed, “isn’t achieved by reason; it’s achieved by charisma, by a feeling of trust that can’t be argued or reasoned, but that comes across in those silences that surround the words. The words are important—but less for what they actually say than for the sense they convey, for the impression they give of the man himself, his hopes, his standards, his competence, his intelligence, his essential humanness, and the directions of history he represents.”

Richard Nixon may have been among the most imperfect and personally awkward individuals to ever run for president. His 1968 victory over Democrat Hubert Humphrey probably had as much to do with Humphrey’s fatal association with President Lyndon Johnson and an increasingly unpopular Vietnam War. That, however, shouldn’t diminish the brilliance of Nixon’s media strategy and how his advisors rehabilitated a once-washed-up politician and helped make him into a president.

Hillary Clinton’s image in not nearly as tarnished as Nixon’s in 1967. Her political challenges aren’t remotely comparable to Nixon’s. Even so, Nixon’s media advisors understood some fundamental truths about rehabilitating a politician’s persona.

It’s a short book. It wouldn’t take Clinton or Schake more than a day to read it. “The Selling of the President,” however, is long on hard-nosed, practical political wisdom. After more than 25 years, the philosophies that Nixon’s advisors followed remain fundamental truths of American politics. “It’s not what’s there that counts,” Price wrote, “it’s what’s projected – and, carrying it one step further, it’s not what’s he projects but rather what the voter receives.”