Bill Clinton’s father died in an automobile accident before he was born in 1946, and his mother Virginia Kelley remarried Roger Clinton in 1950. Bill regularly attended a preschool program at First Baptist Church in Hope, Arkansas, where he learned about Jesus. He also went to its Sunday school and summer Bible school program. His stepfather, who never completed high school, frequently got drunk and often beat his wife. Eager to escape the turmoil at home, at age 6, Bill began walking a mile alone to attend Park Place Baptist Church after his family relocated to Hot Springs, Arkansas. None of his friends attended this church, but Clinton “felt the need” to go. By age 9, Clinton wrote, “I had absorbed enough of my church’s teachings to know that I was a sinner and to want Jesus to save me. So I came down the aisle at the end of Sunday service, professed my faith in Christ, and asked to be baptized.” The pastor, James Fitzgerald, “convinced me that I needed to acknowledge that I was a sinner” and “to accept Christ in my heart, and I did.” Attending church as a child, Clinton later explained, was very important to him. The church provided important moral instruction and helped him understand “what life was all about.” Cora Walters, who served as his family’s housekeeper and nanny for eleven years, had the most spiritual influence on young Clinton. She was an “upright, conscientious, deeply Christian” grandmother, who, according to Clinton’s mother, “lived her Christianity.” In 1959 Clinton attended Billy Graham’s crusade in Little Rock. He was so impressed with Graham’s message and refusal to segregate his audience, especially in the aftermath of the controversy over the integration of Central High School and pressure from the White Citizens Council and Little Rock businessmen, that he began sending part of his allowance to the evangelist.

Clinton’s struggles at home produced what he described as a “major spiritual crisis” at age 13. He experienced religious doubts because he could not prove God’s existence or understand why God created “a world in which so many bad things happened.” Nevertheless, by numerous accounts, Clinton displayed a strong Christian commitment in high school, and some of his teachers thought he might someday become an evangelist. His music teacher and mentor Virgil Spurlin declared that Clinton’s “Christian character and beliefs” always took “priority in his dealings with others." Because of his academic achievement and sterling reputation, Clinton was invited to give the closing prayer at his high school graduation, which expressed his “deep religious convictions.” Clinton beseeched God to “sicken us at the sight of apathy, ignorance, and rejection so that our generation will remove complacency, poverty, and prejudice.” He prayed that “we will never know the misery and muddle of life without purpose.” Clinton claimed in his 2004 autobiography that “I still believe every word I prayed.”

While at Georgetown University from 1964 to 1968, studying philosophy, politics, and economics as a Rhodes Scholar at Oxford from 1968 to 1970, and at Yale Law School from 1970 to 1973, Clinton’s faith had less influence on his life and he attended church sporadically. The Arkansas native’s assessment of Nixon’s 1969 inaugural address provides a window into his spiritual struggles during this period. Nixon’s “preaching of our good old middle-class religion and virtues,” he wrote, “left me pretty cold.” These values could not “solve our problems” with Asians, who did not share the Judeo-Christian tradition; “Communists, who do not even believe in God”; “blacks who have been shafted so often by God-fearing white men that there is hardly any common ground left between them”; and youth, who “prefer dope to the audacious self-delusion of their elders.” “I believed in Christianity and middle-class virtues, too,” Clinton added, but “I thought living out our true religious and political principles would require us to reach deeper and go further than Mr. Nixon was prepared to go.”

In 1975 Clinton married Hillary Rodham, who he had met at Yale Law School, and in 1978 Arkansas residents made him thenation’s youngest governor. The shock of losing his reelection bid in 1980 to a fundamentalist Baptist left him confused, despondent, and adrift. Bill and Hillary had marital problems, and rumors spread that he was having extramarital affairs. These experiences, coupled with the birth of his daughter Chelsea in 1980, brought Clinton back to the church. He joined Immanuel Baptist Church, a 4,000-member Southern Baptist congregation in Little Rock and began singing in the choir and studying the Bible seriously. While critics accused Clinton of attending church to impress Arkansas voters, Betsey Wright, his longtime chief of staff, explained that having “a church family” helped Clinton deal with his traumatic defeat and overcome “what he regarded as his own personal failure.” Clinton benefited greatly from the biblically based sermons and the nonjudgmental spiritual guidance of the church’s pastor W. O. Vaught.

Clinton’s 1981 tour of Israel with Vaught gave him a “deeper appreciation for my own faith, a profound admiration for Israel,” and “some understanding of Palestinian aspirations and grievances.” It produced his “obsession to see all the children of Abraham reconciled on the holy ground” where Christianity, Judaism, and Islam began. After 1980 Hillary’s faith also became very important to her. She read the Bible regularly, filled a notebook with biblical citations, gave numerous lay sermons at Methodist churches in Arkansas, and participated in a women’s prayer group. David Maraniss explains that the Clintons’ faith “eased the burden of their high-profile lives, sometimes offering solace and escape from the contentious world of politics, at other times providing theological support for their political choices.” Their religious pattern reflected that of many other baby boomers: they went to church consistently as adolescents and infrequently during their late teens and twenties. Their faith and church involvement became more important again as they became middle-aged parents. “The intensity of their faith seemed to increase in proportion to their growing ambitions and responsibilities in careers where the rewards of adulation and accomplishment were counterbalanced by the strains of compromise and criticism.”

As Clinton began his presidency, his Christian convictions were on display. The morning of his inauguration, he participated in a stirring worship service at the Metropolitan African Methodist Church. The third week of his presidency Clinton exhorted National Prayer Breakfast guests “to seek the help and guidance of our Lord.” “I have always been touched,” Clinton declared, by the “example of Jesus Christ.” He challenged the audience to “live out the admonition of President Kennedy, that here on Earth God’s work must truly be our own.”

Clinton believed that an all-powerful God had crafted the universe, directed history, aided individuals, and someday would judge everyone. “The world,” Clinton asserted, “was created by, is looked over by, and ultimately will be accountable to one great God.” Clinton accentuated God’s love, righteousness, protection, and providence. By sending His Son Jesus, God demonstrated His “infinite love.” God’s love for every person was “enduring and unconditional.” God’s direction of history was often inscrutable, Clinton told families who had lost loved ones in the bombing of the Federal Building in Oklahoma City in 1995, but, in the words of an old hymn, “Further along we’ll understand why.” “The God of comfort,” the president proclaimed, “is also the God of righteousness.” His justice will prevail, Clinton promised. God’s “amazing grace” enabled people to get “through and beyond our individual and collective sins and trials.”

Clinton frequently referred to Jesus as “our Saviour” and affirmed his belief in Jesus’s miracles and resurrection, “the central event” in the Christian history of salvation. Easter, he proclaimed, demonstrated that “good conquered evil, hope overcame despair, and life triumphed over death.” “God’s only Son,” Clinton declared, brought “the assurance of God’s love and presence in our lives and the promise of salvation.” Jesus is “ ‘the true Light’ that illumines all humankind.” Those who fed the hungry, cared for the sick, nurtured children, and promoted peace and justice reflected Christ’s light. Jesus’s “suffering, death, and rising from the dead” and “victory over sin and death” empowered those who believe in Him to overcome sin. Although Jesus was “born in poverty,” was never elected to any position, and “never had a nickel to his name,” He had “more followers than any politician who ever lived.” Christ’s resurrection demonstrated that love could “triumph over the forces of misunderstanding, fear, and hatred.” Christians, Clinton declared, “celebrate God’s redemptive love as revealed” in Jesus’s life, teachings, sacrificial death, and resurrection.

Clinton contended that God created people of different races in His image as equal and gave them “the right to life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness.” As a result, everyone “had a hunger to find” a meaning in life that transcended “temporal things.” All individuals had “an equal right” to “rise as far as they can go.” “All of us are sinners,” Clinton asserted; everyone has “fallen short of the glory of God.” “Because of flaws in human nature,” he declared, “we’ll have problems until the end of time.” “Evil is a darkness within us all” that “metastasizes and explodes in a few.” “Do not be overcome by evil,” Clinton admonished, “but overcome evil with good.”

Although Clinton believed in “the constancy of sin,” he also affirmed the “possibility of forgiveness, the reality of redemption and the promise of a future life.” As a Baptist, he argued “that salvation is primarily personal and private, that my relationship is directly with God and not through any intermediary.” As a forgiven sinner, he needed “the power of God.” By reflecting “God’s love and forgiveness,” Clinton reasoned, Christians could help end hostilities around the world. They should let their light shine and “give glory to the Father in heaven.”

Clinton testified that worship was important to him. The church, he declared, was “a place not for saints but for sinners.”40 When in Washington, Clinton regularly attended Foundry Methodist Church with Hillary. He also often attended services at Camp David’s Evergreen Chapel with about fifty people and sang in the small choir. As his presidency ended, Clinton thanked the members of Foundry for their prayers and support during the “storm and sunshine of these last 8 years.” He especially appreciated Foundry’s social ministry and its welcoming of Christians of various races, nations, and sexual orientations. Disputing claims that he attended church for political purposes, Clinton insisted that he went because it helped him spiritually and emotionally. His “church home” gave him peace, comfort, and strength. Sunday morning worship was “one of the best hours of the week.” He could take his “Bible, read, listen, sing,” and forget about everything else.

As a child and an adult, Clinton read the Bible from cover to cover numerous times. His childhood friend Patty Criner reported that Clinton owned fifteen Bibles, many of which contained copious handwritten notes. Members of his presidential staff also testified that his Bibles were filled with hundreds of marginal comments. Arkansas political advisor Carol Willis claimed that Clinton often quoted biblical verses, while political strategist Paul Begala insisted that the Democrat had “a deep facility for Scripture” and discussed specific passages in many of their conversations. Clinton avowed that as president he had many “opportunities to be alone and to pray.” He asserted that he read the Bible regularly and the books of numerous Christian authors, including Tony Campolo’s Wake Up America! The Bible, Clinton averred, provided the “answer to all of life’s problems.”

Clinton explained that he read more modern versions of the Bible, but they were “not nearly as eloquent” as the King James Version, his favorite.

Clinton displayed substantial knowledge of the Bible, often making extemporaneous remarks about passages. The Baptist argued that faith is “real and tangible.” “When you believe” in God’s redemption and power, he added, “there’s nothing you can’t do.” Clinton peppered his addresses with biblical citations (almost always the KJV) and allusions and positive examples of congregations and parachurch organizations, especially ones that aided the poor.

Clinton especially liked the book of Psalms. In many Psalms, he asserted, David prayed for the strength to deal with adversity and “his own failures.”

Clinton declared that psalms that focused on trusting in God, following the right path, the importance of wisdom, and God’s unfailing love, faithfulness, forgiveness, salvation, help, and protection of people from their enemies were particularly meaningful to him.

Numerous individuals labeled Clinton’s faith authentic. In 1994, evangelical author Philip Yancey reported, “I have not met a single Christian leader who, after meeting with Clinton, comes away questioning his sincerity.” A Christian college president professed to be “absolutely convinced of his deep and sincere faith” and impressed by Clinton’s knowledge of the Bible. The executive director of the Arkansas State Baptist Convention called Clinton a “genuine born-again believer.” Philip Wogaman, pastor of the Foundry Methodist Church, concluded that Clinton’s faith was “genuine.” Another Clinton confidante, Tony Campolo, a sociology professor at Eastern College in Philadelphia, insisted that Clinton affirmed the Apostles’ Creed and considered “the Bible to be an infallible message from God.” Bill Hybels, pastor of the Willow Creek Community Church near Chicago, declared that in their monthly private meetings he had seen Clinton grow spiritually. Despite such testimonies, many denounced Clinton’s faith as disingenuous because they considered his stances on political issues to be unbiblical.

Clinton argued that all Christians had a calling to serve God. As Martin Luther King, Jr. asserted, a street sweeper should clean the streets as if he “were Michelangelo painting the Sistine Chapel.” By seeking to know and live by God’s will, learning “to forgive ourselves and one another,” and focusing on others, Christians glorified God and provided a positive witness.

In 1992 Clinton stated, “I pray virtually every day.” He asked Americans to pray that political leaders would remember Micah’s admonition to “act justly and love mercy and walk humbly with our God.” Clinton exhorted Americans to ask God for wisdom in raising their children, protecting the environment, and promoting freedom, peace, and human dignity around the globe. He solicited the prayers of Muslims, Jews, and Christians for his “mission of peace in the Middle East.” Clinton also beseeched people to pray for peace in Bosnia, Kosovo, and Northern Ireland. When people did not know how to pray, the Holy Spirit “intercedes for us.” The president often thanked Americans for their prayers and for the encouraging letters and scriptural exhortations many sent him.

Clinton often expressed belief in life after death. When his stepfather was dying of throat cancer in 1967, Clinton assured him that “death doesn’t end a man’s life.” The Baptist explained that he believed in heaven because “I need a second chance.” When Secretary of Commerce Ronald Brown died in 1996, Clinton promised his loved ones that he “was reaping his reward” “in a place where every good quality he ever had has been rendered perfect.” Giving a eulogy for a navy admiral a month later, Clinton declared, he had been “welcomed on the pier by God’s loving, eternal embrace.” At a memorial service for firefighters in Worcester, Massachusetts, Clinton stated, “we commend their souls to God’s eternal loving care.” Those who died in the Oklahoma City bombing, Clinton alleged, “now belong to God. Some day we will be with them.”

While often praising Christianity, Clinton, like other recent presidents, also highlighted the contributions of other religions. “Let us,” he declared in 1994, “rededicate ourselves to the spirit of Easter, of Passover, of Ramadan” “and to the common values” that “make America a land of limitless hope and opportunity for all.” He had “been immeasurably enriched by the power of the Torah, the beauty of the Koran, the piercing insights of the religions of East and South Asia and of our own Native Americans, [and] the joyful energy that I have felt in black and Pentecostal churches.”

As president, Clinton had a close relationship with five ministers—Rex Horne, Jr., who served as his pastor at the Immanuel Baptist Church in Little Rock from 1990 to 2006; Bill Hybels; and a trio of ministers who counseled him after his affair with Monica Lewinsky—J. Philip Wogaman, Tony Campolo, and Gordon MacDonald, pastor of Grace Chapel near Boston. Horne discussed a variety of matters with Clinton in weekly phone calls, in frequent letters, and sometimes in person. As president, Clinton occasionally worshipped at and regularly gave money to Immanuel Baptist Church, and Horne sometimes sent him video tapes of his sermons and other religious materials. The minister asserted in 1994 that he sought to aid Clinton in his spiritual journey. Horne insisted that “I have never been an apologist for the president. I have just tried to be his pastor.” He did complain, however, that many Christians had unfairly judged Clinton’s faith and policies. Rather than focusing on criticizing Clinton’s views of abortion and gay civil rights, with which Horne also publicly disagreed, Christians should support the president’s efforts to fight racial injustice and aid the poor. Clinton looked to Horne for spiritual guidance and thanked him for being “such a good friend, counselor, and source of inspiration.” Shortly before leaving office in January 2001, Clinton told Horne that “your friendship, prayers, and support over the years” has “meant a lot to me.”

In an October 1997 letter to Horne, Paige Patterson, the president of the Southeastern Baptist Theological Seminary in Wake Forest, North Carolina, denounced Clinton’s appointment of Virginia Apuzzo, a “lesbian activist,” to direct the White House management shop, as a “breach of Christian conduct.” He argued that 1 Corinthians 5 mandated that if a parishioner’s sin was “widely known in the church and beyond,” it must discipline and even exclude him. Patterson recognized that this action was “thoroughly unthinkable” and had “political overtones,” but he argued that Clinton was unlikely to “make any substantive changes in his lifestyle if he is not confronted” in such a way. Immanuel Baptist did not discipline Clinton, but in 1999 Horne wrote the president to protest his proclamation of Gay and Lesbian Pride Month.

Clinton responded that he respected Horne’s views on homosexuality and stressed that his proclamation had not taken “a position on homosexuality as a religious matter.” Instead, it recognized the nation’s diversity and highlighted “initiatives aimed at ending discrimination, violence, and intolerance based on sexual orientation.”

Hybels met with the president in the White House almost monthly and asked Clinton “point blank” questions about his spiritual life. They also discussed political issues and prayed together. As Clinton’s pastor in Washington and spiritual counselor, Wogaman conversed frequently with the president. Clinton thanked Wogaman for being his minister, advisor, and friend. Campolo, a strong advocate of social justice, evangelism, and missions, met with Clinton about once a month to pray about personal and policy matters. Clinton also met periodically with MacDonald the last two years of his presidency. MacDonald had resigned from Grace Chapel in 1987 after publicly admitting to having an affair. Following a two-year “restoration process,” MacDonald published Rebuilding Your Broken World about his experience, which Clinton read.

All of these ministers said that their conversations with Clinton focused on prayer, the Bible, and personal spiritual growth. Clinton claimed that these relationships helped him “stay centered” and remain “humble and optimistic.” The demands of the presidency, Clinton insisted, could crowd out everything that kept its occupants “growing and whole.” His spiritual counselors helped him immeasurably because they did not seek to please him, tell him what he wanted to hear, or try to get something from him.

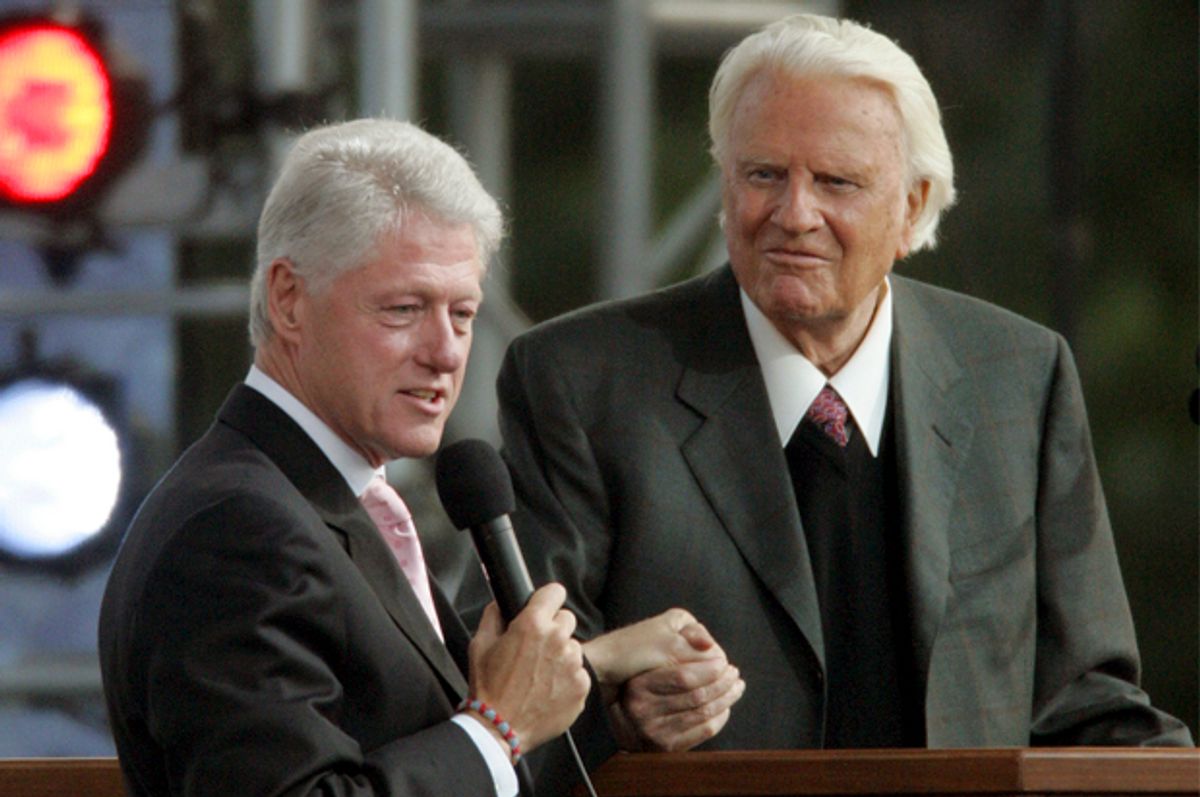

During his presidency Clinton had numerous exchanges with Billy Graham. In March 1995 Clinton congratulated Graham on his “Global Mission,” which was designed to reach more than one billion people in 185 nations. In November 1995 Clinton told Graham that he felt strengthened by his prayers and hoped that God would use him as “a special agent” to help millions around the world. Asking Graham to participate in his second inaugural ceremony, Clinton wrote, “your counsel, friendship, and prayers have long been a source of strength and joy to me.” Graham assured Clinton everyone who was present was deeply impressed by his tenderness and love in comforting mourners after the bombing of the Federal Building in Oklahoma City in April 1995. Soon after accounts of Clinton’s alleged affair with Lewinsky began to surface in March 1998, Graham declared that he would forgive Clinton, “a remarkable man” who had faced “a lot of temptations,” if he were indeed guilty. While the Clintons were comforted by Graham’s statement, other theological conservatives criticized his promise of blanket forgiveness.

Excerpted from "Religion in the Oval Office: The Religious Lives of American Presidents" by Gary Scott Smith. Published by Oxford University Press. Copyright 2015 by Gary Scott Smith. Reprinted by permission of the publisher. All rights reserved.

Shares