“Saturday Night Live” almost never made it past 1980. Lorne Michaels left after five seasons, after hoping to simply step away from the show for a year to explore other projects. But instead of allowing his trusted hands Al Franken, Tom Davis and Jim Downey to run the show, NBC appointed associate producer Jean Doumanian -- then cut her budget in half and gave her three months to sign writers and a cast. She did hire breakout stars Joe Piscopo and Eddie Murphy, but Season 6 was considered a critical and commercial disaster, and she was fired after 10 months.

Her replacement, Dick Ebersol, had his work cut out for him, trying to redefine the vision of “SNL.” He built around Murphy and Piscopo, and while focusing on stars made ratings sense, it was frustrating for the new talent. As a result, there was a lot of turnover.

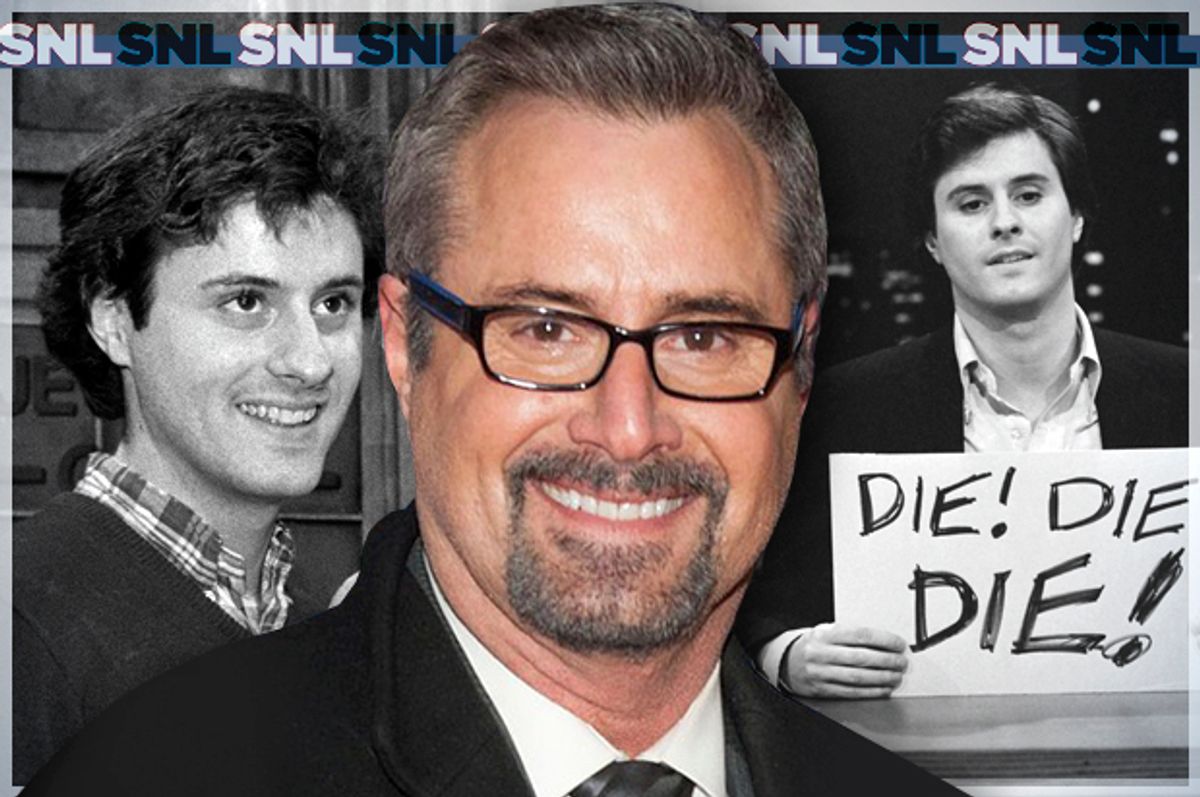

It wasn’t until Season 8 that people had staying power, when Ebersol brought on a trio of talented Northwestern alums, from Chicago’s Practical Theater Company, who stuck around until Lorne’s return in 1985: Julia Louis Dreyfus, Brad Hall and Gary Kroeger (his official “SNL” archive is here).

Kroeger tells Salon that despite the fact that Reagan was in office, "SNL" shied away from political satire at the time—a source of frustration for a left-leaning comic in the Reagan era. (Kroeger announced on April 6 that he’s running for Congress, representing Iowa’s 1st District.) Still, he had an opportunity to play the ill-fated 1984 presidential candidate Walter Mondale, though he was perhaps best known for Ira Needleman, the singing dentist, and a killer Alan Alda impression that puts Bill Hader’s on notice. The dashing Kroeger, whose dark, wavy hair and warm, brown eyes made him the perfect person to portray Donny Osmond, opposite Louis-Dreyfus’ Marie, as the Mormon brother-and-sister duo performed “Blue Christmas” and got entangled in an incestuous makeout session.

Kroeger was reflective and gracious in conversation even as he revealed his mixed feelings about being a supporting player, in which every sketch had to be built around Murphy and Piscopo. He also explains his decision to leave full-time acting to return to his native Iowa, his philosophy about the intersection of politics and comedy, and the deep respect he has for the brilliant, as yet unparalleled social observations about race and class that Murphy brought to the show.

This is the second installment of our interview series with "SNL" alums, which started earlier this month with this Nora Dunn conversation.

You took your teenage son to the "SNL 40" reunion -- and wrote a great piece about it, which appeared on Salon. He must have been over the moon. How many kids do you have?

I have a 15-year-old son and a 10-year-old son—the apples of my eye.

So he wasn’t even an apple in your eye when you were on the show. Of course, he knew about your "SNL" existence, yes?

Previously his dad was nothing more than a decent Google. Seriously. I’ve always had an interesting career. I’ve led myself into the business world as I moved back to Iowa, being a local fundraiser, charity worker, so on and so forth. So my kids have always seen me in the public eye to some degree. They know that their dad’s different than most dads. But this “SNL” thing … it wasn’t about me, it was about my kid meeting Paul Rudd, Mike Myers, Eddie Murphy, Kristin Wiig. That was mind-blowing for a teenager.

You worked with Eddie Murphy for a couple of years.

Yeah. And my son got a kick, and so did I, out of the fact that people that he knew came up and said, “Hey, Kroeger, how you doing?” I was beaming with pride for my son and in myself, I guess I could say.

I read that Eddie Murphy asked to audition for the show during Jean Doumanian’s brief tenure as the producer. He was 19 years old.

Yeah, Eddie’s career really took off just before I got there. When I came, it would have been his third year. His second year, he started to emerge. By the time I got there, “48 Hours” just opened and he was suddenly a superstar.

That was an interesting and weird time for “SNL” because Lorne Michaels and the Not Ready for Prime Time Players had left, and the network was trying to rebuild the show. New producer Dick Ebersol had a reputation for being as quick to hire as he was quick to fire, so the morale couldn’t have been great on the set.

Yes and no. When Lorne Michaels left the show, I think he kind of thought the show would be over. But NBC wanted to keep its late-night powerhouse, and Dick Ebersol was part of the original programming, so NBC said, “Dick, can you keep this show alive?” Well, that’s not entirely true because Jean Doumanian had a year in 1981; the show was critically slammed, the numbers went down. I think Dick Ebersol was brought in to save the show. And he did just that. He identified emerging stars Eddie Murphy and Joe Piscopo, and he hung the show around them. I was hired the next year, along with Julia Louis-Dreyfus and Brad Hall because Dick saw in us that same renegade, garage mentality that was the original “Not Ready for Prime Time.”

You three went to school together.

Yes, we all went to Northwestern together—we were in the Practical Theater Company. They hired us to really rattle the cage and keep Eddie sharp. It worked. Eddie’s career took off. The show centered around him. So we were hired, but immediately marginalized in terms of our contribution to the show. And it really continued that way through our time on the show. Julia is one of the biggest stars ever to emerge, but she didn’t emerge from that show.

Yes, first with “Seinfeld,” but not until “Veep” did we really get to see her freak flag fly again.

“Veep” is a perfect marriage of person and part. So was “The New Adventures of Old Christine.” I believe she got a couple of Emmys from that one. It was a terrific show, but it wasn’t a water-cooler show, like “Seinfeld” was, and like “Veep” is.

Random bit of trivia I learned when I interviewed Megan Mullally for New York magazine a few years ago: She used to go out with Brad Hall before Julia.

Sure did. That’s how I met Brad Hall. He was dating Megan Mullally. I did a play with Megan Mullally at Northwestern and Megan and I were friends, she introduced us. Brad and I became great friends. I knew Julia before I knew Brad—she and I were good friends and she met Brad Hall.

So did their love blossom at Studio 8H?

Well, it had already blossomed. The train had left the station. We all knew they’d get married. It wasn’t until right after “SNL” that they did get married.

What was it like to be a supporting player? You three were hired because you have so much talent, and then your producer is saying you have to incorporate Eddie or Joe Piscopo into every sketch. That had to have been frustrating.

It was frustrating. But at the same time we’d never had a different experience. We realized what was up pretty much as soon as we got there. I don’t mean to slam Dick Ebersol. He gave me a job, he even rehired me after I was let go after my first year. Dick is a friend. But we did call him the “George Steinbrenner of comedy.” He hired the big bats. And we understood, I think secretly. I always wished I had been part of the Lorne Michaels era, because I believed and I still believe, I would have been nurtured. I’m very good at what I do. I think I could have emerged as a major force on that show, if brought along correctly. Those aren’t sour grapes. It’s just the way it was. At the end of every week, I said, “Hey, I’m getting paid to live in New York. Life could be a lot worse than this.”

It was an interesting time too. When “SNL” started, New York was in financial dire straits, heading the way of Detroit.

Yes, it was still the New York that was considered the most dangerous city on Earth. They were proud of that in a way. It was a flag to be waved. New York had that swagger of being the elite of the elite, and at the same time a place of the streets. New York was about survival and it was about being the shining city on the top of the hill at the same time.

You were on the show during Reagan’s first term, which I imagine felt a lot different than during the Ford and Carter eras—a very different vibe.

It was a different vibe. We had the benefit of Mayor Ed Koch, who became a friend, and who was a wonderful man, and a great progressive. He did the show twice while I was there. I was delighted to spend time with him. I loved Mayor Koch. Mayor Koch was New York. He grew up a New Yorker, remained a New Yorker, he loved New York. At the same time, this was the beginning of the Reagan era. Brad Hall and I always felt the show should have a much more political edge, like it does now. But it didn’t. We did Reagan sketches, but they weren’t political, they were cartoony. We had always felt that “SNL’s” strongest hand was when it was satirical, especially with politics. It was not the personality of the show at that time.

I remember seeing a short called “White Like Me,” in which Eddie Murphy experiences white privilege. It was quite bold, bolder than anything I’ve seen on the show now. He puts on whiteface, and goes to a newsstand, and the clerk won’t let him pay for his paper. He discovers when there are no black people on a bus, the white people party, with cocktails and lap dances.

It was controversial then, and it remains controversial. It was a tremendous statement on systemic racism—tremendous. I would hold that up in the pantheon of the best satire that “SNL” has ever done. That was also somewhat of a departure, I think, for the show. Eddie’s popularity and many of his characters were based on that perception of race. Eddie was a champion of black consciousness. He satirized racism in a way that called attention to it very successfully. That was the most socially relevant stuff that the show had, either at the time and probably ever has. I can’t speak for Eddie, but I think that he would be very proud. I can’t even tell you all the names of the characters—he played a straight guy that wrote poetry and did art, that was very much of the streets, but the white upper-class intelligentsia just considered it so novel and worthy of applause. But really he was making fun of the white aristocracy. We did that very effectively. “SNL” also parodied media very well. Again, with Eddie, the “killing of Buckwheat,” a horrible stereotype, but turning it into a mega media star. We satirized media at the time, and how we would re-create the shooting of Buckwheat and play it over and over. It was a comment on media saturation as good as anything ever.

And of course this was years before CNN.

Yes! All we had was “Nightline” and Ted Koppel. But already, we were seeing what media could do to stir up a story and perpetuate it.

I think the Reagan attempted assassination and John Lennon assassination were probably the first times we saw that. Those were the first times we saw these repeat plays, I think.

The Buckwheat assassination was a very deliberate parody of the Reagan assassination attempt.

So if you and Brad and Julia were there to support Eddie and Joe, were you able to get your own sketches on the air?

Well, it’s a good question, not an easy answer necessarily. The pitch process wasn’t really a pitch process. Everybody was required to write. Anything that featured me was probably written by me. It was very clear to the writers (which performers) you were writing for to get your material on, and that was Eddie and Joe. We understood that. But Brad and I, and Julia and another writer there named Paul Barrosse who came with us, we were trying to re-create what we did at the Practical Theater. And very successfully in theater we did what we called guerrilla comedy and it was very political, very satirical. We were trying to bring that to “Saturday Night Live.” But it was an era of cartoonish humor. We didn’t know how to create characters like Buckwheat or the sports guy—it just wasn’t in our tool chest. Brad and I had this thing called the “upside-down family,” and it was just this on-going series of people who live upside down. It’s hard to describe, but we wanted to turn TV upside-down and we figured this was the avenue, that was “SNL.” So we spun our wheels for a long time trying to figure out "How do you come up with catchphrases?" How do you come up with characters that the writers want to write? What’s our version of the “Bees” or the “Coneheads”? We were fish out of water.

Did it feel like two city sensibilities clashing, with these Chicagoans in a very gritty New York?

Yeah, we had allies in Tim Kazurinsky and Mary Gross, who came from Chicago’s Second City. They had seen our theater work, and so had Dick Ebersol. And they loved what they saw. But it wasn’t an easy translation to bring to television. Truth be told, we were probably very naïve. I can’t say that our stuff would have worked, the theatricality of our stuff, on TV. But we were simply never shown, or given, the help from the producers or the writers to bring us along.

It seems like today there is more room for absurdity; perhaps if you and Brad were doing it today, you’d have a bit more room for upside-down people.

You know, I can’t tell. I’ve always felt that it would be better for me today. We were the first kind of big cast. When I was there with Billy Crystal, Marty Short, Jim Belushi, Harry Shearer, Pamela Stephenson, Rich Hall, Chris Guest, Julia, seems like I’ve forgotten somebody. I mean, that was a big cast. Talk about about hard to get on the show. But I don’t know if I should look back on my time and go, “You know what, I got enough stuff to put together a home reel to thrill my great-grandchildren; maybe I should thank my lucky stars that I was there when I was." It’s just hard to tell. I get to look at this way: I’ve always been in a semi-elite club.

What was your “SNL” audition like?

My audition had two phases to it. I didn’t audition. Julia and Brad and I were doing a play in Chicago—that was our theatrical improv comedy show right next door to Second City. We were a big hit. I was hoping maybe I’d get a commercial out of it or something, something to maybe put gas in my car. And then we heard that the producers of “SNL,” Dick Ebersol and Bob Tischler were in the audience and wanted to talk to us. Now previous to that, I was asked to put something on tape that would be sent to “SNL.” I went in front of my agent in Chicago in fall of 1982 and I just did all of my impressions and characters back-to-back on tape, that I’m told went to Dick Ebersol. But I didn’t feel like I was auditioning for anything. It was just this weird little thing I was asked to do. On the basis of that tape, so I’m told, Dick said let’s go check these people out in Chicago. So we were just doing are show one night and got a call the next morning to show up at his hotel and he said "Can you be in New York in two weeks"" So that was painless. Painless! I’ll give anything to see that tape today. I’ve never been able to find it.

Did you watch a lot of “SNL”?

I was a fan of the beginning of “SNL.” I started college when it started on the air and Dan Aykroyd, Belushi and all of those guys—I was a huge fan. In the two years after Ebersol left, I was aware of Piscopo and Eddie Murphy. But to me, Joe Piscopo was the star. I loved his name, he was the guy I couldn’t wait to meet when I got there.

What was the production week like when you were there?

Didn’t change at all. They took the template from Lorne Michaels and I’m sure it’s what he uses today. Monday night you start talking about ideas. Tuesday, all night you are writing ideas. Wednesday you get together late-morning, everybody—cast, crew, producers— are in a room and you read through everything. The show was always about a half hour too long and you would cut a half hour after the dress rehearsal. Very often that would be my stuff.

Is that true? Or does it just feel like that for everybody?

No, because the softer stuff or the stuff in my era that didn’t feature Eddie was always the stuff that was the first on the chopping block. Very often you’d get a promise that it’d be in the show next week, but very often the next week was a new week, and the old material didn’t see the light of day.

Were there any knock-down, drag-out fights?

Yeah. You know, if you’re a writer or actor and your stuff gets cut, and it was good, and it gets cut again the next week — “SNL” is a wonderful experience, but it also tests the limits of human emotions. There wasn’t a week where somebody didn’t cry.

You’re working long hours among a small group of people, with lots of ego and talent on the line, and everyone vying for airtime.

My nickname from Dick Ebersol was “No problem Kroeg.” And although I appreciated it, I was flattered by it, the fact that I didn’t make trouble probably hurt my career. I was easily overlooked because I didn’t make waves. I’m proud of that as a human being, but as an actor trying to get seen on “SNL,” that didn’t work to my advantage.

Who was the squeakiest wheel outside of Eddie and Joe?

Well, they weren’t squeaky wheels. They were handed this job by their talent. I would say everybody that was hired as a star, or given the opportunity to be a star, had no reason to be squeaky. Yes, there were a couple of people that were very difficult if they didn’t get what they wanted. You know, I got shoved aside a couple of times and it hurt. But we’re all grown-ups now. They’ve made peace with me and so I’m good with it.

Are you still friends with a lot of people you were on the show with?

Well, that was the beauty of going back. There’s people I haven’t seen in 30 years and just like Eddie Murphy saying “Hey, Kroeg, how ya doing?” I consider them all friends. I’ve stayed close with Brad Hall. Tim Kazurinsky and I see each other now and again. He’s touring with “Wicked.” Some of the writers I’m still in touch with: Andy Breckman, Kevin Kelton.

What were some of your favorite sketches that you did while you were on? Your Dorothy Michaels was spot-on.

Well, that was a fabrication by me to get on the show. Because I knew if I did that, it was a hot movie, and if I put Eddie Murphy in it, it would get put on the show. And it worked. But it was not a favorite memory of mine.

Ira Needleman, the dirty dentist who did a rock video for a date, people still talk about it. I was proud of my Walter Mondale impression. And a couple of times, I did have a character that if only the writers had gotten behind it, I think it would have done well, it was this nerdy high school kid that was called “El Dorko” and he was persecuted by people, but always came out the victor in the end. And I always liked that message. I did it a couple of times and the audience just loved him, and I always wondered why the writers didn’t help me expand on him.

Those are the things I look most proudly on. I am very proud of the fact that people could turn to me and say "Kroeger, could you work up an Alan Alda impression," and I could do it and find my way onto the show, or "Kroeger, could you work up Robert Mitchum" and I could do it, and find my way onto the show. I was very proud of the fact that I had a good ear, and could work very quickly. I still think I do the best Alan Alda of anybody on the planet. I think I had a chance to do him two or three times.

Here’s another I’m proud of: There was this thing called “The Red Guy’s Rap.” Jim Belushi liked doing these raps. And he did this thing called “The Red Guy Rap,” two Soviet defectors who came on and did rap music. And it’s Saturday and it’s Jim and Rich Hall. And for whatever reason, Jim decided not to do it. So without any rehearsal, I went and did it live—well, the dress rehearsal, then live. I had to learn the song quickly. I put on a bald cap, created this Russian character, and mimicked Jim’s moves and sang the same song off of cue cards, which you almost can’t tell. I am extremely proud of that.

It seems like there’s a lot more cue-card reading now than there ever was.

Cue cards have always been there, from the beginning. Except for that one time, I didn’t use them. I was from a theatrical background, and you learn your lines. I don’t think Juila used cue cards either, for the most part. We were very theatrical. When I do see the show, I know when their eyes are going over to cue cards. Before I did the show, I didn’t know they used cue cards. And I just thought their eyes were moving around. When I did the show and I realized everything was on cards, especially the guest host needs the cards, I realized that’s what that eye glance means.

Chevy Chase used to use it in a funny way when he was doing the news. It was sort of the running joke, the way he didn’t know which camera to look at. Now, when I watch, the characters aren’t even looking at each other because they’re too busy reading cue cards.

I notice it. The show goes up very fast. They don’t start blocking anything really until the day before. So there’s really no way to do it otherwise, without there being mistake after mistake. Sometimes actors can get away without using them. I did, but I didn’t have much to do for the most part, so it wasn’t that hard for me.

How much room was there for improv?

Sometimes things fall apart, and you improvise. And those moments are brilliant, because most of the actors up there are improv actors, like we were. But most of it is on the script and it is read exactly as it was written, most of it.

It’s very easy to let an F-bomb fly, as we’ve seen with Charles Rocket and Jenny Slate.

In my day, at least, there was no delay. I don’t know if there is now, but there was no delay as was the case of Charles Rocket. So if it went out, it went out. Most of the ad-libs came from something happening that was unexpected or an actor laughing or whatever, and the audience kind of knows that something spontaneous is happening. I never had a problem. It’s all about concentration. But you know what, Jimmy Fallon learned long ago, the audience loves crack-ups. And the audience does. It’s called pulling a Harvey Korman—great actor, great comedian—but Tim Conway would make him laugh, and when he did, the audience loved it. And so I think the trigger mechanism is created, where you want to go to that place where you enjoy what’s going on and you make the audience enjoy it as well.

As we enter Election 2016, I think about the arsenal of political impressions “SNL” has built over 40 years, some of which have even changed middle America’s mind about candidates, like Tina Fey’s Sarah Palin. And some may forget how much of an impact Will Ferrell had with his Dubya.

And Dana Carvey, with George Bush Sr.

And his Ross Perot. Talk about a gift for a comedian, that guy, together with Stockdale!

That’s where “SNL” is at its most effective, when it actually tickles popular culture and casts a glaring light onto politics. That was an era that wasn’t my era. I did Walter Mondale but I certainly didn’t change the tide of perceptions. He only barely got into the public consciousness. It really was a landslide. But the debates—we didn’t take advantage of the political climate. A Mondale-Reagan debate, that would be a slam-dunk today. We didn’t do it. It would have given me a platform for starters, but just not what we did.

You have an interesting perspective because not only have you been a satirist, you’re now one of them! You’re running for Congress in Iowa. So you know intimately the absurdity, as you begin your campaign. Are things more absurd now than they were back in your “SNL’s” day? I feel like candidates are dumber than ever.

I never like to call them the dumber, but they’re the disenfranchised non-intellectuals who now have a voice and are actually moving the needle. The uninformed now have a much bigger voice. They’re louder. By non-intellectuals I don’t mean stupid, I just mean those who just don’t want to engage in the minutia, pull up their sleeves, and do the math. They are from-the-hip voters.

Okay, so maybe more like the defiantly ignorant. Like this Idaho lawmaker a month or so ago who asked if women can swallow a small camera for a gynecological exam—lawmakers who are legislating women’s bodies and who don’t know basic anatomy.

It’s certainly seems that more of those people are being elected. At least we’re hearing about them. They’re being exposed now. But you’re right. How does that person get enough votes to get in the car and move to Washington? It is baffling.

I was reminiscing with a friend about those circus-like GOP debates in 2011, and they looked like “SNL” sketches—and in fact became spoofed on the show—with Michele Bachmann, Sarah Palin, Rick Perry, Rick Santorum, and Herman “9-9-9” Cain. Mitt Romney was the only candidate among them you could listen to without thinking, “WTF?”

They’re all still being listened to. They were just in Des Moines at the Conservative Coalition speaking one after the other. It is baffling that the audience is still there. They’re still there. That is why it is more important than ever for progressives to dig into our heels and define “progressivism” and not be afraid of what it is we stand for. Because we do stand for civil rights, human rights, environmental rights, educational rights. We believe in effective government. We have this crazy notion that the aggregate voice of the people should be strong. But that’s why I’m running, and it’s as a true progressive who believes in, I use the word “egalitarianism,” and my campaign manager says stop using that word. But I have a feeling most people understand the concept that we are deserving of equal voice isn’t that outrageous.

I think people could get on board with that. Well, I would hope so, at least.

I’ll take 51 percent. What I watched in the last cycle was Democrats seem scared. They didn’t want to talk about gay rights. If they didn’t want to talk about a woman’s right to choose, they didn’t. But in my little stump speeches so far [we spoke before he declared his candidacy, on April 6], which are anywhere from two to 14 people, I take those issues on. I say what I believe. I believe if the Democratic Party doesn’t talk about the issues that are tough, then those people who look to us for help, for a voice, they feel betrayed. They are betrayed. If not us, then who? There’s no reason for me if I’m just another Democrat trying to win. There’s no reason for me to run if that’s what I’m doing, if I try to tailor myself into being the perfect candidate. You know what? Google me, you’ll find out that I didn’t come out of a textbook of perfect candidates. “SNL,” for God sakes.

Al Franken did it.

But, you know, Al built his new reputation on his books rather than on his comedy from the past. He was very successful writing really well-researched condemnations of the far right and found a new voice. He’s taken very seriously, and I will be too. But I don’t have a bunch of books to my credit—I’m a neophyte. I’m just a guy with ideas and a loud mouth.

Have you been in touch with him?

I’ve met him before. He had heard about my potential candidacy. But I did sense that he’s being very careful not to endorse another “SNL”-turned-politico. He does still have to fight, I think, for his non-comedic credibility. And I think he’s conscious of that. I just sense that, so I simply didn’t push it.

It’s not so strange to see someone in satire get into the business of politics because it’s your job to see the issues, and the world of politics with more focus—it’s your job to do so, in order to pick them apart.

You made the best point of the day. I actually said just that with Steve Kornacki on MSNBC, which I did before the “SNL” reunion. Artists, satirists, we look at the world more closely with a deeper-focused lens. We do look at politics, the human condition, with a laser focus. We find the ironies, the contradictions, the double standards, because that’s what creates our art. And it lends itself to beautifully to politics, to creating policy and legislation in looking at all angles of an equation.

Shares