In 1949, some of the country’s top advertising executives launched a national marketing campaign. They weren’t selling a physical product. They were selling religion. Before long, the Religion in American Life campaign was placing close to 10,000 newspaper ads per year, coordinating national radio marketing, and putting up thousands of billboards, all intended “to accent the importance of all religious institutions as the basis of American life.” Major corporations bankrolled the effort.

We tend to imagine public expressions of faith as rising spontaneously from the American people, for good or for ill. When a politician says “God bless America,” she’s trying to sound like a populist, not like a corporate pawn. But as Princeton historian Kevin Kruse details in a new book, "One Nation Under God: How Corporate America Invented Christian America," our country’s religious slogans owe more to corporate campaigns than they do to grassroots work.

As Kruse argues, in the wake of the New Deal, business leaders linked Christianity, Republican politics and libertarian economics, helping drive a wave of public piety in the 1950s. The decade gave us our national motto, In God We Trust (born in 1956), and a new line in the Pledge of Allegiance, “one nation under God” (dating to 1954, this American tradition is as old as Burger King and Denzel Washington).

Reached by phone, Kruse spoke with Salon about the red scare, Billy Graham and why the fiercest opponents of school prayer tend to be religious.

Let’s say I’m a CEO in 1930s America. Why does promoting Christianity make business sense for my company?

Once the New Deal is underway, that’s the big player. With the regulatory state underway and labor unions on the rise, business leaders saw themselves on the fringes, and they tried to push back. They did so originally with a mass program of public relations. The National Association of Manufacturers spent 22 times more on PR in 1937 than they had in 1934. So they’re pouring a massive amount of money into this, but they’re not getting anything back.

The reason they start making this argument about freedom under God is that it’s a much more effective way to push back against the regulatory state and the labor unions. It’s no longer businessmen making the case for businesses. It’s ministers.

How did you make the regulatory state sound ungodly?

They just declare it ungodly. The phrase that they often use is “pagan statism.” [Corporations] advance the idea that unfettered capitalism and Christianity are soul mates, and they do this by arguing that both have essentially the same approach to the individual.

In Christianity, the individual rises to heaven or falls to hell based on his or her own character. They say the free market is just like that. You succeed, you fail, on your own. In their eyes, the state meddles with that purity. That’s the natural process. That’s the godly process. So anything that is working against the system that God himself must have set up, the system of individual merit, must itself be ungodly.

As you detail in the book, thousands of ministers were happy to take this message and run with it. Why?

For the ministers at the top — Reverend James Fifield, Billy Graham, people like that — the appeal is that they really are ministering to the elite. James Fifield’s congregation [in Los Angeles] was filled with millionaires. When he talks to parishioners about their concerns, he naturally sees their point of view, and he’s sympathetic to their needs, as any good minister to his flock would be.

But they expanded beyond just ministers who have wealthy parishioners. They’re very effective at making this argument that a state that restricts capitalism will inevitably restrict Christianity. They link economic restrictions with religious restrictions. It requires a bit of a leap of faith, but it’s one that they effectively sell. This out-of-control state is coming for them all.

It seems like quite a stretch to draw libertarian economic principles out of the Gospels.

It is not the Bible I was taught as a child, for sure. They do this by a very selective reading. These are not fundamentalist churches by any means. In fact, theologically, they’re quite liberal. As Reverend Fifield says, reading the Bible should be like eating fish. Not all parts are of equal value. We take out the bones to eat the meat. Fifield disregards all of Christ’s warnings about the dangers of wealth. He completely disregards the injunction to look out for one another. To love your neighbor, to be your brother’s keeper. He discards all of those messages. It becomes a faith of individualism.

This all feels very Protestant, maybe specifically Calvinist: the wealthy as an ordained elect.

In a way, yes. If you conflated Christianity and capitalism in this way, yes, I think the idea of an elect is there. If you succeeded in one realm, it’s a sign of God’s favor upon you. It’s a belief that being wealthy is not a hindrance to your heavenly progress. It’s a sign of it.

So was Fifield the Joel Osteen of the 1940s?

A little bit. There had been prosperity gospel types before this. What’s different about this moment is that the state factors in considerably. This is where the libertarian angle comes in. Before the New Deal, you don’t really have a massive federal government that’s seen in the eyes of business leaders as meddling in their world. With the New Deal, you have. Suddenly this relationship between capitalism and Christianity is set in relief to this obtrusive federal government.

Would the federal government have made such an easy villain for some Christians if communism weren’t perceived as a growing threat?

A large number of these attacks individuals made on the New Deal are ones that characterize it as socialist or communist. And here’s where the state comes into relief as ungodly. Communism in this country is always held up as atheistic communism.

Were there particular sectors of corporate America that seemed to get particularly strongly behind this?

Manufacturing is strongly behind it. Steel and auto are strongly behind it. I think it’s no coincidence that those are the few sectors that faced the harshest strikes by the CIO in the late ’30s.

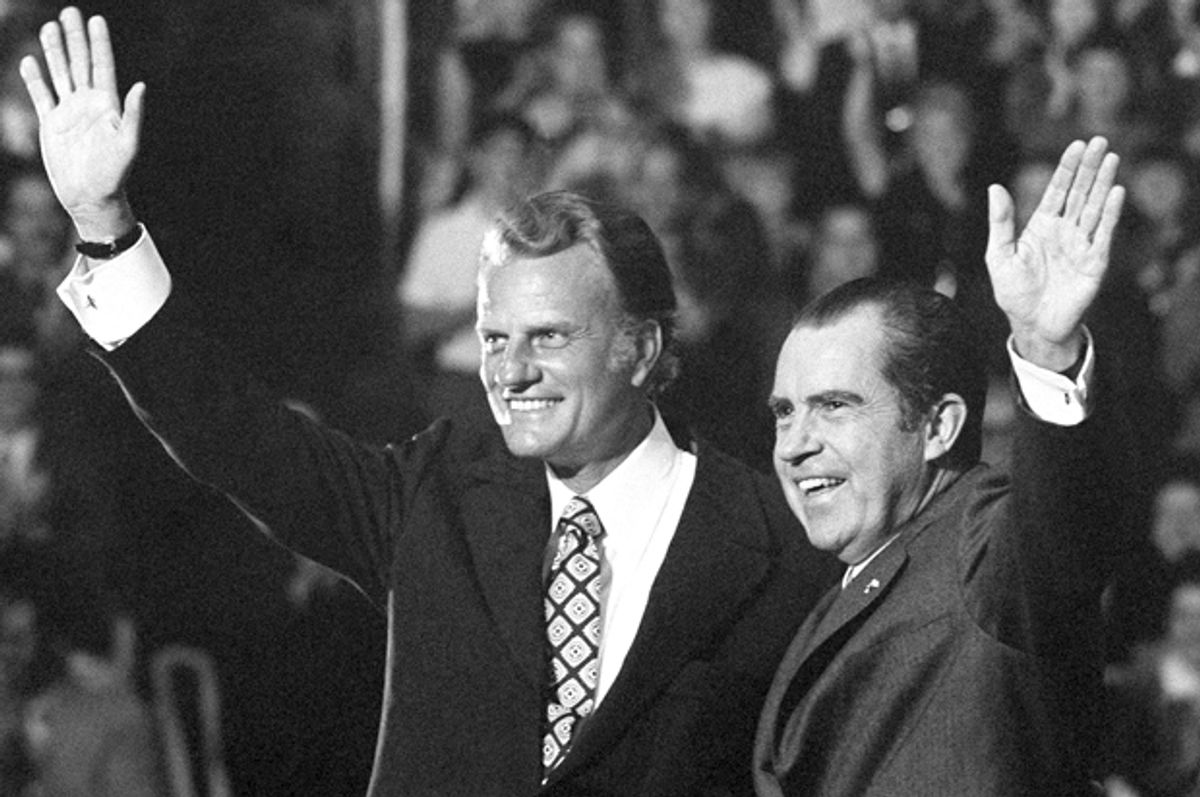

Billy Graham is a central figure to your book. He’s there right at the birth of this Christian libertarianism, and he just keeps on popping up again and again. Why did Graham gravitate toward these corporate titans?

I think he gravitated to them because they found him very early on in his career, and they were very enthusiastic sponsors of him. [Time magazine founder] Henry Luce meets with Graham early on and starts promoting his work. William Randolph Hearst, soon after Graham’s first revival in Los Angeles, sends a two-word telegram out to all of his newspapers that says “Puff Graham.” Early on, he had allies among these corporate leaders. He got to know them as individuals, and he’s very empathetic and comes to see the world as they see it.

Out of all the evangelists in the country, why did these guys pick Graham?

I think they saw that he’s an incredibly talented preacher. He’s very charismatic. He’s very telegenic. He’s a handsome young man and he has the ability to hold a crowd in the palm of his hand. I think they realized that if they could harness that messenger, that their message in his hands would be incredibly effective.

But even Graham has been hesitant to openly endorse politicians like Dwight Eisenhower, whom he knew well. We have this national tradition of ministerial neutrality, don’t we?

There’s a tradition, and a lot of it comes from the fact that to get involved in politics means certain penalties to pay, especially with your tax-exempt status. Graham is a good model in this — he never officially endorses a lot of people, but he makes it very clear where he’s voting.

Franklin Roosevelt, Truman, Lincoln and other presidents evoked religion regularly. But your book focuses on Eisenhower’s use of religion during his presidency. What made it distinctive?

Only after Eisenhower’s in office, in 1953, does he get baptized. But he was always a believer in a very kind of broad and all-encompassing religion. He often speaks of Judeo-Christianity, so it’s not even just a broad Christianity. He welcomes the Jews as well as Catholics and Protestants. His critics deride him for being a very firm believer in a very vague religion. But he understands that that kind of vague religion is incredibly powerful in the hands of a president — that you don’t come out on the side of one sect or another, but instead embrace all believers and make them feel like they’re all invested in the same vision for the country. That’s powerful, and I think he shows it’s incredibly effective.

This is right after WWII, right at the start of the Cold War. It’s a nationalistic period. It seems like these credos about God and country were functioning as nationalist rallying points, in a country where people don’t share an ethnic or racial history.

Maybe the way to think about that is the shift in mottos in this period. It had never officially been the country’s motto, but many people had assumed it was: E Pluribus Unum. Out of many people, one. But what you see here is a shift away from that kind of a unity built out of diversity to a unity built out of divinity, in One Nation Under God.

Does it work? Do you think people feel more united through these religious mottos at first?

That’s hard to say. I don’t know if I have an answer to that. I think it’s fairly effective. You can see it in contemporary politics — the staying power of these logos and slogans. They certainly have incredible power. Whether they’re truly uniting people — that shifts over time.

As you argue in your book, slogans that were introduced in the 1950s to unify people became culture war flashpoints by the 1970s.

You can see the way in which these slogans operate in Eisenhower’s hands as opposed to Nixon’s hands. Eisenhower really divorces this religious language from its partisan political roots. These things have been built up by people who were opposed to the New Deal and had seen them as a way to roll back the New Deal. Eisenhower thinks that’s a fool’s errand. He expands the New Deal. But he thinks his religious language is important on its own terms. And again, by divorcing it from its partisan roots and even from its Protestant roots, he makes it into something that welcomes in virtually all Americans. Atheists are still on the outside.

Nixon, however, uses the same language in a very different way. He doesn’t use it to unite people. He uses it as a way to push divisive political issues. He uses it to advance domestic issues of the silent majority. He uses it as political cover when he widens the Vietnam War to Cambodia and student protests break out. In using this language that’s meant to bring people together, he only alienates them and drives them further apart.

Do you think that was just a reflections of Nixon’s style, or did it reflect broader changes in the United States between those two presidencies?

I think it’s mostly Nixon’s approach to these things. But I do think that the ground shifts considerably between when Eisenhower leaves office in 1961 and Nixon enters office in 1969.

It shifts largely on the issue of school prayer. Eisenhower’s success was keeping this religion incredibly vague. It’s One Nation Under God. In God We Trust. It rarely gets beyond that almost bumper-sticker level of politics. The problem is as you try to put these broad national slogans in the classroom, administrators and teachers have to provide the same level of precision for their religious instruction as they would for any other kind of instruction, and that means picking a particular faith’s bible.

You see it become much more divisive than it’s ever been before. By the time Nixon takes power, a lot of the allure has already worn off these phrases. So it’s not entirely his fault. The way in which he tries to apply them — to sell the invasion of Cambodia, to paper over hard-edged social policy for the silent majority — I think that really is what sealed the deal. It brought the partisan edge back into these phrases that had once united Americans, and that now drove them apart.

Did the corporations end up benefiting from their campaign to push faith into the public sphere?

I don’t think [they benefited] much at all. Their ultimate goal had been to elect someone like Eisenhower and then have him use this language to roll back the New Deal. Instead, he expanded it. I really think the story here is one of unintended consequences. It had been launched to roll back the New Deal and instead it helps inspire a new sort of religious nationalism.

Today, it’s easy to forget that having “In God We Trust” on our money, or the idea of “one nation under God,” dates back to the 1950s — instead of, say, the 1770s. Why did these slogans come to feel so traditional so quickly?

I think a lot of it has to do with their pervasiveness. They’re everywhere. In the pledge. In our wallets. Carved into the walls of Capitol Hill and our courts. They appear frequently in the speeches of our politicians, and because they’re so pervasive, we assume they’ve done this forever. We don’t think they have a history at all. If you were to ask most Americans, they would say that these things have been here from the start.

They start to take effect and quickly build upon each other. Every new example is used as an excuse to have the next one. If we have this thing, why don’t we have this as well? It starts to snowball from there, and as it does, it takes on a size that makes it hard to imagine it had ever been any other way.

Is there any example of the reverse trend, in which an expression of public piety gets rolled back? School prayer, maybe?

But then the fight for school prayer becomes a perennial [issue], at least on the right. When “under God” is being added to the pledge, no politician will vote against this. It’d be like voting against motherhood. Once you propose these things, they’re almost automatically going to happen. And by the same logic, it’s inconceivable that they could be removed, at least by politicians. The courts have made a stab here and there, with school prayer especially. But the idea that politicians who need to curry favor with the voters who’ve come to expect this sort of thing — that they would intervene — is almost unimaginable.

We often feel like politics are getting more religious, but you could also say that religion is getting more secular. It goes both ways, right? These changes shape Christianity, not just politics.

I’d assume that this fight over school prayer would be religious groups all lined up in favor, and some atheists on the other side. But it’s religious leaders who fight very strongly against these things, because they feel that the state is invading their own world and taking over their responsibilities. There is a feeling that religion is becoming corrupted by the state. The people who are most opposed to school prayer aren’t atheists. Instead, they’re people who take their religion very seriously and don’t want it reduced to a one-size-fits-all faith.

Do Democrats and Republicans go about using faith in different ways?

I think it’s a difference of degree, not kind. There’s an expectation that Republican candidates will make this kind of appeal, and I also think the audience is receptive of it. There are certainly many of people of faith on the left, but there are also a significant number of atheists and secularists. And that’s a line that a Democrat has to walk and a Republican does not: how to appeal to both of those groups. Obama tried this out by calling us a nation of believers and non-believers. That was a major moment.

But is it possible today to have a truly secular candidate? Are we ever going to see someone try to run essentially a secular campaign?

I think it’s possible to try. Michael Dukakis came pretty close. The way in which polls of religious identification are trending — I think at some point, sure. Millennials are much less attached to any individual faith. As they come of age, if those patterns maintain, I think you could see a truly secular candidate not only run but win.

This conversation makes me wonder if a freethinker like Thomas Jefferson would be a viable presidential candidate post-Eisenhower (setting aside all the other sordid details of Jefferson’s life).

If it came out that a presidential candidate had cut out all mentions of miracles in the Bible with a razor, I think he would not do too well. So on those grounds, I think Jefferson would be immediately barred. Even a full-throated defense of separation of church and state would probably do him in.

Shares