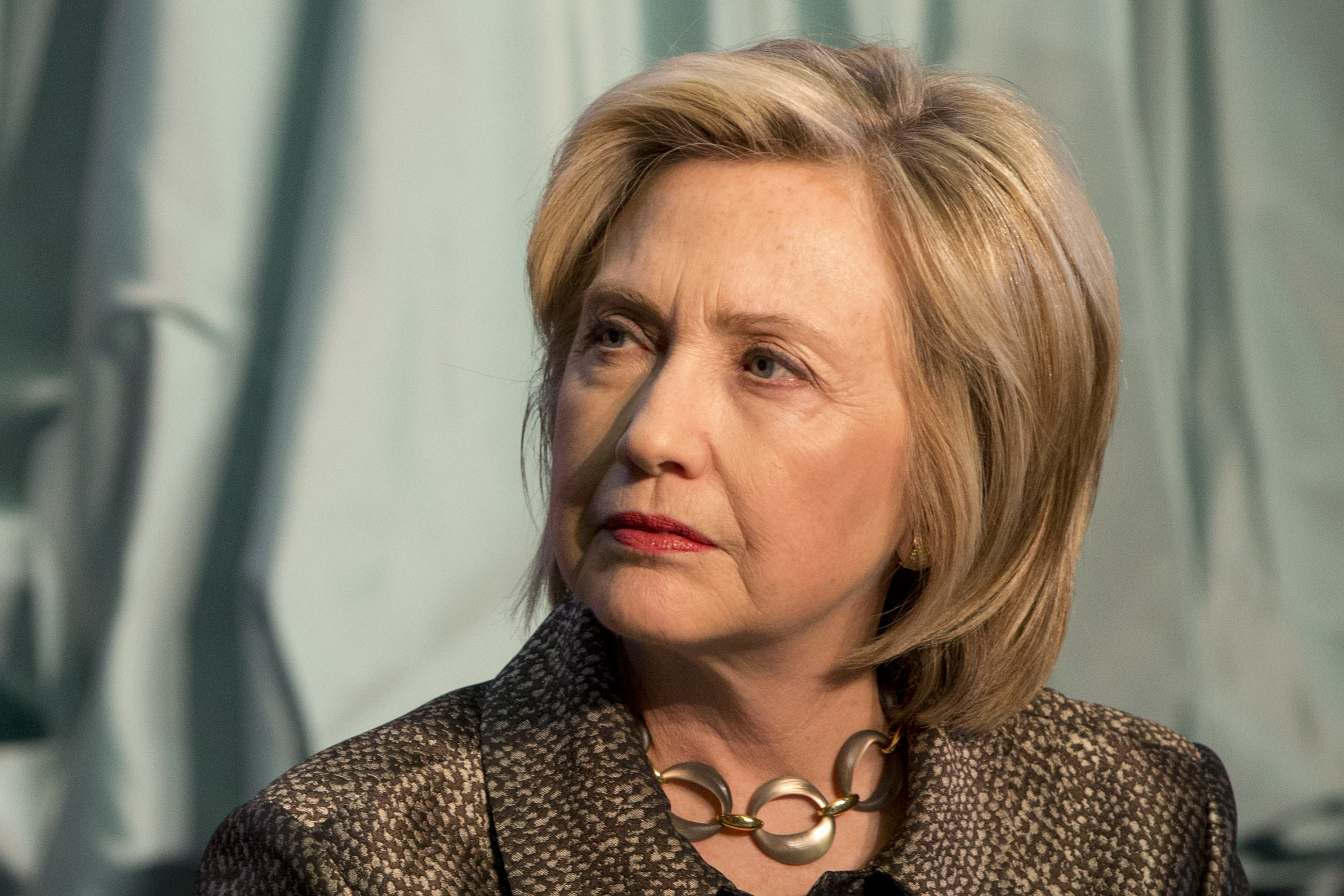

It’s quite unlikely that I’m telling you anything you don’t know already, but when it comes to Hillary Clinton’s 2016 presidential campaign, the ratio between words journalists have written and events worth the journalists’ writing has thus far been badly askew. (I’d argue that that’s largely a consequence of forces beyond the individual reporters’ control; and I’d certainly not hold myself up as blameless.)

Regardless, it’s thankfully starting to look like that imbalance might be at least somewhat mitigated. Because if the former secretary of state’s campaign is full of speeches like the one on mass incarceration she delivered Wednesday morning in New York, there’s a chance — just a chance — that 2016 might not be as much of a tedious, meaningless slog as we’ve feared.

Before we get into the good of the speech, though, let’s start with the bad. The Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act of 1994 — which was written by then-Sen. Joe Biden, proudly championed by then-President Bill Clinton, supported by Hillary Clinton, and likely contributed to the mass incarceration she decried in her speech — went entirely unmentioned. As the Nation’s Dave Zirin snarked on Twitter (I’d say somewhat hyperbolically but, hey, this is Twitter), the idea of a President Clinton crusading against over-criminalization is, for those who remember the ‘90s, a little discordant:

[embedtweet id=593420700771319808]

[embedtweet id=593421543243386880]

[embedtweet id=593422540862787585]

Now, there’s been a bit of a conversation this week as to whether lefties should particularly care if Clinton’s halting embrace of mainstream liberalism is sincere. The New Republic’s Brian Beutler, the American Prospect’s Paul Waldman, and the Washington Post’s Greg Sargent say they should not. The New York Times’ Amy Chozick implies they should. I’m in the former camp; I don’t particularly care whether it’s because she’s craven or a true believer who now feels emboldened to speak her mind. Part of what is supposed to make democracy work, in fact, is that the distinction makes no difference.

Still, it’s hardly out of bounds for Zirin to point out what is at least a superficial hypocrisy. That’s not to say it’s one Clinton should find especially difficult to overcome — she’s not her husband, after all; the early ‘90s were a very different time, politically; and part of being a good leader is a willingness to change your mind — but she can’t just outright ignore it in perpetuity, either. (Of course, the same dynamic is even more relevant with regard to her talk of “toppling” the 1 percent; and it’s not a coincidence that the part of her Wednesday speech that most fell flat was a quip about exorbitant Wall Street bonuses.)

The rest of Clinton’s speech, however, was really quite good — and those who want to see criminal justice reform and inequality at the center of her campaign have reason to be optimistic. She seems to endorse placing body-cameras on all cops (the actual language left room to wiggle) as well as stopping local police departments from using federal funding to “buy weapons of war that have no place on our streets.” More importantly, she consistently tied these policy tweaks to a broader theme of economic inequality, describing “talk about smart policing and reforming the criminal justice system” as worthless unless paired with “talk about what’s needed to provide economic opportunity.”

Granted, as Clinton herself acknowledged, “it is not enough just to … give speeches about [criminal justice reform]” without accompanying them with action. We are fast-approaching the point where a high-level politician like Clinton should no longer earn extra-credit simply for talking about mass incarceration or inequality. The two topics are rather decisively no longer taboo; and Clinton isn’t getting out ahead of public opinion here so much as showing a willingness to believe that it’s not 1996 anymore, and that the public has caught up to where most educated, left-of-center elites have been for some time already.

But the main reason why Clinton’s Wednesday speech has me feeling a bit more (cautiously) optimistic is not because I expect her to traipse across Iowa talking like Michelle Alexander. No, it’s because the speech suggests that she won’t have to be pulled, kicking and screaming, away from the hyper-cautious, defensive centrism that defined her husband. And because a speech like this gives a whole lot more to write, think and talk about than hypotheticals about how some faceless swing voter in Ohio might feel about a damn “homebrew” server.