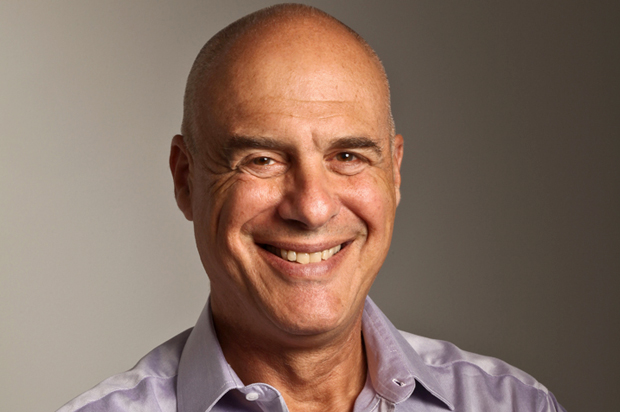

Four years ago, Mark Bittman exploded onto the New York Times editorial page with a manifesto chock-full of ideas for how to reform — and, to some degree, revolutionize — America’s food system. As fitting for the former Minimalist, it was an 818-word jumping point for what would become an ongoing conversation about he we can “make the growing, preparation and consumption of food healthier, saner, more productive, less damaging and more enduring.”

Francis Lam, then Salon’s resident food writer, called the match “perfect.” And in the years since, Bittman’s become a leading voice in what you might call our current food movement (more on that below), helping a generation of eaters and writers (ahem) understand the at-times wonky, at-times inscrutable state of American food.

If “How to Cook Everything” (or “How to Cook Everything Vegetarian”) is the go-to source for the intrepid home chef, then “A Bone to Pick,” a new collection of Bittman’s columns and features, is destined to become a staple for those who want to consider, more deeply, what’s on their plate. Salon’s conversation with Bittman, which has been lightly edited for clarity, follows:

With the book coming out, this seems like a good time for a retrospective on your column, and the way that your thinking about food has evolved since it started in 2011. I was thinking especially about these key issues that you laid out in your inaugural column: government subsidies, processed food, promoting small farmers and home cooking, fixing food labels — these big issues that you felt were important to address first. Looking back on that, are these still the things you’d prioritize? Or has the landscape changed at all for you?

I think that original manifesto is still pretty much what you’d want if you could ask for something.

Do you feel that there’s been any progress made on any of those areas so far?

Well you know this landscape as well as I do, but let’s look. End government subsidies to processed foods? No. Begin subsidies for those that produce and sell actual food for direct consumption? It’s increased by $50 million or something like that over four years — not much. Break up the USDA and empower the FDA? No. Outlaw concentrated animal feeding operations and encourage the development of sustainable animal husbandry? No. Encourage and subsidize home cooking? No, although I guess you could say “My Plate” was a step forward. Tax the marketing and sale of unhealthful foods? Well, there’s a soda tax in Berkeley. Reduce waste and encourage recycling? No. Mandate truth in labeling? There is going to be an improvement in the food label but it’s still unlikely to have a recommendation on limiting the amount or percentage of sugar in your diet, so… Reinvest in research? No. So I’d say it’s all still pretty valid and we haven’t seen much progress. I don’t know, would you disagree?

I don’t think I would. You highlighted a lot of intractable problems, ones that may require some long-term thinking.

Well, they require some determination. I think a lot of this stuff is pretty easy to figure out. It’s just the same old story: there hasn’t been the political will. There are a couple of things that are not on that list that could have been but that we’ve actually seen improvement on. We have seen improvement on school lunches, and that’s thanks to a really sound effort from President Obama. It’s far from perfect, but it’s really making a difference.

The other thing we could have seen progress on is getting antibiotics out of animal husbandry, and we haven’t seen that, which is a real failure of the FDA and the Obama administration. The fact that people are excited because corporate America is taking voluntary steps to reduce the use of antibiotics in the food supply… It’s certainly better than nothing that they’re doing that, but we can’t rely on their goodwill. They’ve made pledges before and not carried them out. I think this needs to be mandated, there need to be rules; it can’t be like, we hope there will be fewer antibiotics. That’s not an adequate way of dealing with this.

And it’s more pressing, time-wise.

Right. The next question is, what should we be doing that we’re not doing? And I’m not quite sure I know the answer to that. There are still valid demands that there hasn’t been enough activity on, and what will it take? I really thought we were going to see action on antibiotics from the FDA under the Obama administration before he was out of office, but he’s putting all his chips on climate change — which is certainly not a bad place to be putting your chips, but it’s not doing the food world that much good.

One other thing that’s changed in the last four years is the attention being paid to workers in food. Fast-food workers really started this Fight for $15, and people have picked up on it. That’s really a positive step, and that’s something that’s happened through the hard work of a lot of people and through the recognition that this is a very important issue. The food movement talked about animals for a long time, and now the food movement is talking more about workers, and I think that’s a big change.

One reason I think we have to be more optimistic is that people are starting to get interested in these issues, especially through things like your column. You write a lot about what the media chooses to cover or what it doesn’t — do you notice a lot of response to what you’re writing?

I’m not a pollster. It’s hard for me to know what people are interested in and what they’re not. I can judge how successful my columns are, but that’s not an accurate gauge of response to something that we’re talking about. Being here in Berkeley and talking to students, I do have a sense that there’s an understanding of a bigger picture. No one really thinks they can shop their way out of this stuff anymore, that the biggest questions facing us are whether food is organic or whether there are GMOs in food. It’s clear that these are really huge issues and that they’re going to take a long time to resolve, and that they require thought and work.

I really don’t know how to say what should be done next or what’s the most important issue or what’s going to be the hot-button topic in the next few years. I will say that the fact that people are taking labor issues more seriously is really important, and I think that ties into income inequality, and now you’re really looking at the big, big issues that are facing our society, facing our country. Food is definitely a part of that: food affects everything and everything affects food. I’m not saying that when kids get killed by cops, these are food issues, but I am saying that people are beginning to see the links among all these things. What we have here is not a plutocracy but something very close to a plutocracy, and it’s important for the rulers to keep people in line. It’s not just food or just income inequality that are being used as tools to keep people from being active, but all of the above.

I really appreciated the column you wrote on that at the end of last year; it was eye-opening. I’m wondering, do you see there being a coherent food movement in the US?

Question of the year! For better or worse, the two places where there are activities that could be called food movements are, one, the Fight for $15 — and that’s a big deal; a lot of that is a movement around food, so that qualifies — and the second is the GMO-labeling movement, but I think a lot of that energy is misguided. Even though it’s misguided, I think that if we wound up with GMO labeling, it wouldn’t be the worst thing in the world because we do want transparency, and that would be the be the beginning of some kind of transparency that we haven’t seen to date. I’ve said this before and I can say it more: I’d rather know if there are antibiotics being used to produce my food than if there are GMOs being used; I’d rather know if there are underpaid workers; I’d rather know if there are pesticide residues. I’m much more interested in that; I’d rather know if there was animal cruelty.

Those are two things that I think are examples of movements. Is there an anti-pesticide movement? Is there an animal-welfare movement? I guess there is a shopping-for-better-food movement, but for the most part, Americans are very good at shopping. If you make anything about shopping, we’ll become experts quickly. Is there something else? This is not rhetorical — is there something I’m not thinking of that you would say is a evidence of a food movement?

I think of the idea of getting artificial additives out of food. That’s definitely an example of where there’s a lot of passion and movement, but not necessarily heading in the right direction.

Where do you even see that happening? I must be missing something.

Have you been following The Food Babe at all?

I’ve heard of her, yeah.

She has a huge online following for campaigns like getting the chemicals out of your Starbucks frappuccino. I see the point about why you wouldn’t want some things in your food supply, but a lot of where she comes from isn’t paying so much attention to science; it’s rooted in a deep fear of any kind of chemical or additive. It looks over problems like added sugar in favor of something that sounds scarier than that. So I’m wondering, how do we harness energy like that and push it in a better direction?

I don’t know how, to be honest. I think we need people who want to be organizers; I think we see that in the Fight for $15. It’s not your traditional labor movement tactics, per se, but we need traditional labor movement people, and those people are organizers. I’m not copping out of that, but I’m not an organizer. I know that when there’s organization and we have goals and have organizers, things happen. To the extent that things happen, they don’t happen spontaneously. For example, the Sierra Club has a goal of closing every coal plant in the country, and they’ve already closed more than 150, and they have organizers all over the country doing that kind of work. If there were a real food movement and the food movement were to say: the goal is to make sure no one who works in food production gets paid less than $15 an hour; or, we want to make sure that every school system is adhering to the new HHFKA [Healthy Hunger-Free Kids Act] standards, those things would have an impact. Those are organized.

So how do we get to that place? I don’t know, but I think that’s the next step. What I do I do? I write about issues which I think are important, but I don’t go out there and pound the pavements and knock on doors and try to make sure people are paying attention to these issues. But if we want to make progress, someone needs to do that.

I guess the most we can hope is to inspire someone to think that’s worth doing.

I think that is our job.

Going forward with your column, where do you see it going?

I don’t think there are new issues. I think some stuff will come up, there will be some newsy things now and then, but I don’t think we’re going to have to reinvent anything. We know what the issues are. We have to work on them; there will be progress. There has been some progress on antibiotic use, but much of it is disappointing because we could have gone much deeper on this in the last few years. Antibiotics is going to remain an issue for a long time; pesticides; herbicides, especially the ones associated with GMOs; improving school lunches; improving diet for everybody; limiting junk food marketing to kids — that is, to me, a critical issue that’s not getting addressed hardly at all.

Nothing I’m saying is anything you and I haven’t talked about together or at least thought about. It’s not like I have some secret issue and you don’t know to write about it; nothing that would change the conversation. It’s just going to be this gradual hammering away at the same issues, I believe, and hopefully over the course of the next x years making a couple of them significantly better. I don’t know how you move past HHFKA to whatever the next step is, but I do know we have a presidential election coming up and we want to make sure that candidates address that. How do you feel about marketing junk food to children? What can we do about limiting that or changing that? How do you feel about antibiotics in our food supply? All of this needs to be asked to anybody who’s running for office, and that’s a job that for food movement or for you and me right now.

Anybody who cares about food should be going to community meetings and directly addressing candidates, both Republicans and Democrats, about the five issues in food that they care most about and asking for their position on it. I think the five issues may vary from person to person or place to place — like, if you live in Iowa, I think one of your issues is water quality. I’m sure you know the city of Des Moines is suing the surrounding countries about water quality, so that’s an issue there, but here in California, maybe the issue is regulating the use of water in agriculture; in the Northeast, it might be what we can do to support a return to local farming. We also all have issues in common, like CAFOs or antibiotics or pesticide residues or junk food marketing to children. How many issues are there? Six or 8 or 10, and you could break those down into 20 or 30 if you wanted to. You can make the discussion as big as you want, but if you want to make the discussion smaller you can, and you can keep these conversations sort of narrow. You can say that there are ten issues, even 4, that we care the most about and we’re going to try to get candidates to respond to us on these things and to give us the answers. How can you help us stop the use of antibiotics in livestock production? How can you help to stop the pollution of surrounding water and land by CATOs? Et cetera. I sound like a broken record…

It’s at the risk of repeating ourselves that we hammer down on these same key issues.

I think you do repeat yourself, but as soon as there’s no more antibiotics being used in the food supply we’ll stop talking about antibiotics in the food supply and go on to something else. As soon as there’s no junk food being marketed to kids, we won’t have to talk about that anymore, but until there’s progress on those things, it does sound repetitive, but it’s repetitive because there’s been no activity. There’s been little or no improvement.