Every post-apocalyptic tale is a utopian dream in disguise, which makes our current cultural obsession with the theme — from TV series like “The Walking Dead” to literary fiction like “Station Eleven” — a little less mystifying. Or does it? Humanity could really make something of itself, these stories suggest, if only we could first clear all these people out of the way.

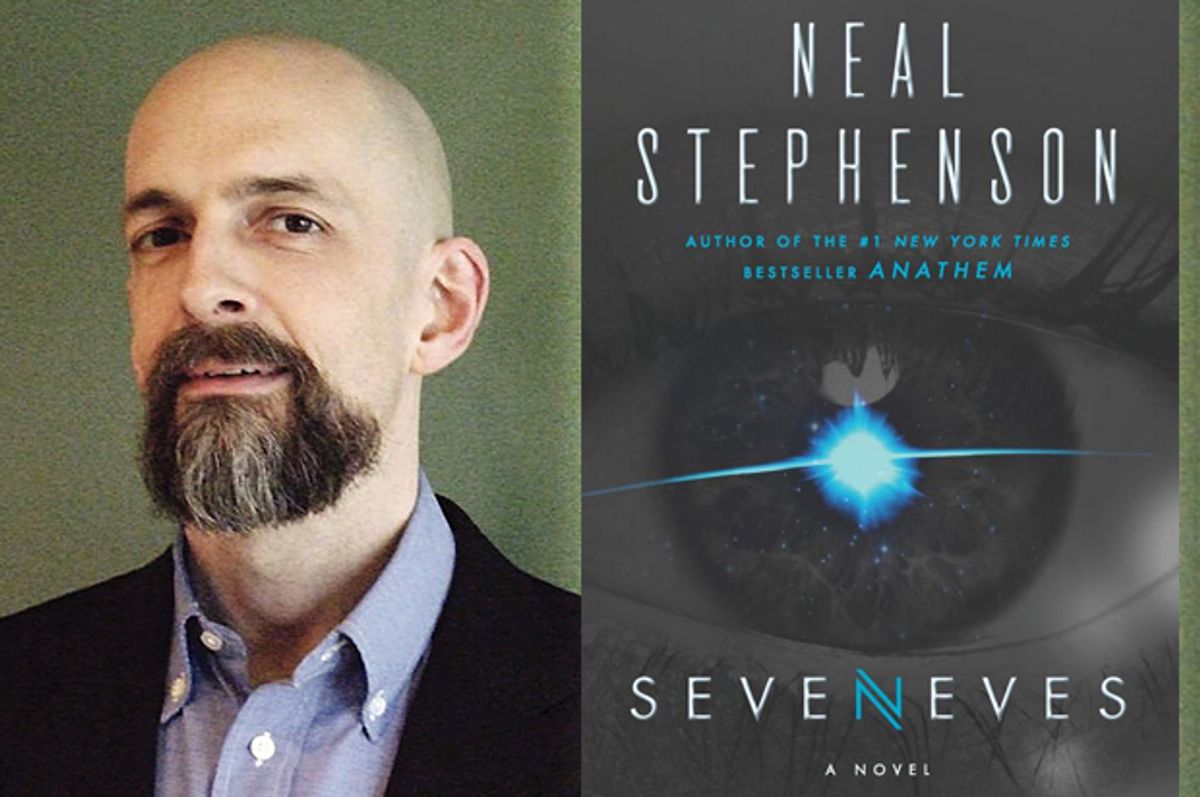

Neal Stephenson’s sweeping new science-fiction novel, “Seveneves,” is a post-post-apocalyptic yarn. Its first part recounts the desperate attempt to save humankind from an unimaginable catastrophe and the second is a knowing interrogation of just how difficult it is to leave our species’ past behind. In the book’s pivotal scene, eight women sit around a battered conference table in a former space station fastened to a clump of rock hurtling through space. They’re all that’s left of the human race; will they be able to keep it going? Is it even worth the try?

“Seveneves” begins with panache: “The moon blew up without warning and for no apparent reason,” goes its first sentence. Yet this is a matter-of-fact bravado, with all the hysteria scrubbed out of it. The usual fictional apocalypse these days is viewed from the perspective of Joe or Jane Average, some poor slob who barely understands what’s going on and who just wants to get back to his or her family. “Seveneves” is about the sort of people who, when the moon blows up, have to figure out what to do about it.

Stephenson’s main characters for this first section include Dubois “Doob” Harris, a black astrophysicist and media personality who bears no small resemblance to Neil deGrasse Tyson. (If the real moon actually did explode into seven large pieces, Tyson would surely be the man tasked with explaining it to us.) The other is Dinah MacQuarie, a punningly named miner’s daughter who runs a hoard of robots working on an asteroid attached to the International Space Station. In “Seveneves,” Doob goes on TV to inform the public that, since the lunar mass is still more or less the same, people needn’t fret so much about the tides. He also supplies the bigger fragments with kid-friendly nicknames like “Kidney Bean” and “Mr. Spinny.” (“It wouldn’t do to call them Nemesis or Thor or Grond.”)

Doob is also among the first to realize that the lunar bust-up (caused by forces unknown) won’t stop there, that the pieces will keep colliding with each other and breaking apart into smaller and smaller fragments. “The good news,” he tells President Julia Bliss Flaherty, “is that the Earth is one day going to have a beautiful system of rings, just like Saturn.” But the bad news is really, really bad. Within two years, pulverized rocks will blanket the sky and begin to fall into the Earth’s atmosphere. “There will be so many of them,” says Doob, “that they’ll merge into a dome of fire that will set aflame anything that can see it. The entire surface of the Earth will be sterilized.”Also, he estimates this “Hard Rain” will last at least 5,000 years.

Whelp, time to get cracking. While world leaders break the news, Dinah, her good friend and commander Ivy Xiao and a team of scientists, specialists and astronauts are deputized to assemble the Cloud Ark, a biological and cultural time capsule that will carry a few hundred people and enough genetic data to eventually reconstitute all terrestrial life forms. The station, nicknamed “Izzy,” is Stephenson country, an engineer’s paradise, filled with smart, brave oddballs figuring out how to do the seemingly impossible on the fly, using the aerospace equivalent of rubber bands and duct tape. (Sometimes it’s even actual duct tape.) That the whole enterprise might be hopeless and really just a sop to soothe Earth’s doomed billions as they go into that good night is a notion many of the novel’s characters suspect, but few dare to speak of.

Unlike, say, 95 percent of novelists, Stephenson is largely on the side of the engineers. When some practical problem very much needs to be solved, here are the people to do it, even if they aren’t very good with small talk, or get exasperated by politics and can’t fathom the other characters’ obsession with social abstractions like “the narrative.” Yet Stephenson is himself a novelist; he knows the life-sustaining power of storytelling, since storytelling is what he does. The tension between the frenetic effort on Izzy to jerry-rig a self-sustaining colony in space and the mournful solemnity of the people of Earth as they dutifully gather plant samples and priceless cultural artifacts for the Cloud Ark (most of which will never make it off the planet) slowly builds until the fatal day arrives. Today’s post-apocalyptic stories routinely aim to convey the loss of the old world through the personal losses of a few characters. Stephenson makes you feel the loss of Earth on the scale it deserves.

Granted, most of the first part of “Seveneves” is preoccupied with the nuts-and-bolts of creating and powering the Cloud Ark, including a semi-insane scheme to tow a gigantic lump of ice from the other side of the sun. This stuff will be catnip to some readers and daunting to others. Falling somewhere in the middle of that spectrum myself, I enjoyed it as the aerospace version of all those how-to passages about maple sugar boiling in “The Little House on the Prairie” books. It leaves you with a similarly vague and no doubt misguided feeling that, in a pinch, you might be able to pull off some of these tasks yourself. (Stephenson has been affiliated with privately funded space-travel company Blue Origin, so all of these bits have the ring of authenticity.)

But while the engineers and other capable people running Izzy field one technical challenge after another (orbital decay! radiation! random pebbles shooting out of the void faster than a speeding bullet!), they drop the ball on the whole narrative thing, as technocrats are all too wont to do. By the end of the first section of the novel, when those eight desperate women (only seven of whom are of childbearing age, hence the title) face each other across that conference table, things look pretty bleak for the human race.

Then, with a boldness to match the novel’s opener, the story jumps ahead 5,000 years. Somehow (it will be revealed how only gradually), the Seven Eves managed to found a spectacular new civilization in the ring system surrounding Earth. The refugees are finally venturing back on the surface of their devastated planet, where surprises await, but what’s most arresting about this world is Stephenson’s vision of what can be changed about human nature and what — despite the best genetic engineering — cannot. Race as we now know it no longer exists, but tribalism and clans, tracing their lineages back to the Seven Eves, remain. In what is perhaps a bit of wishful thinking on the author’s part, most of humanity has learned to pick and choose which technologies it employs, wisely bailing on social media as irredeemably toxic. Yet some people still read printed books.

The bulk of this second section is taken up with an adventure story in the inimitably swashbuckling Stephenson mode. Yet the can-do characters in this plotline are not as disastrously naive as the technocrats of the Cloud Ark. They’ve realized that the most important question to ask when founding a new Earth is not “How?” but “Why?” You can save humanity, relocate it, redeem and transform it, but it will never be made up of anything better than people.

Shares