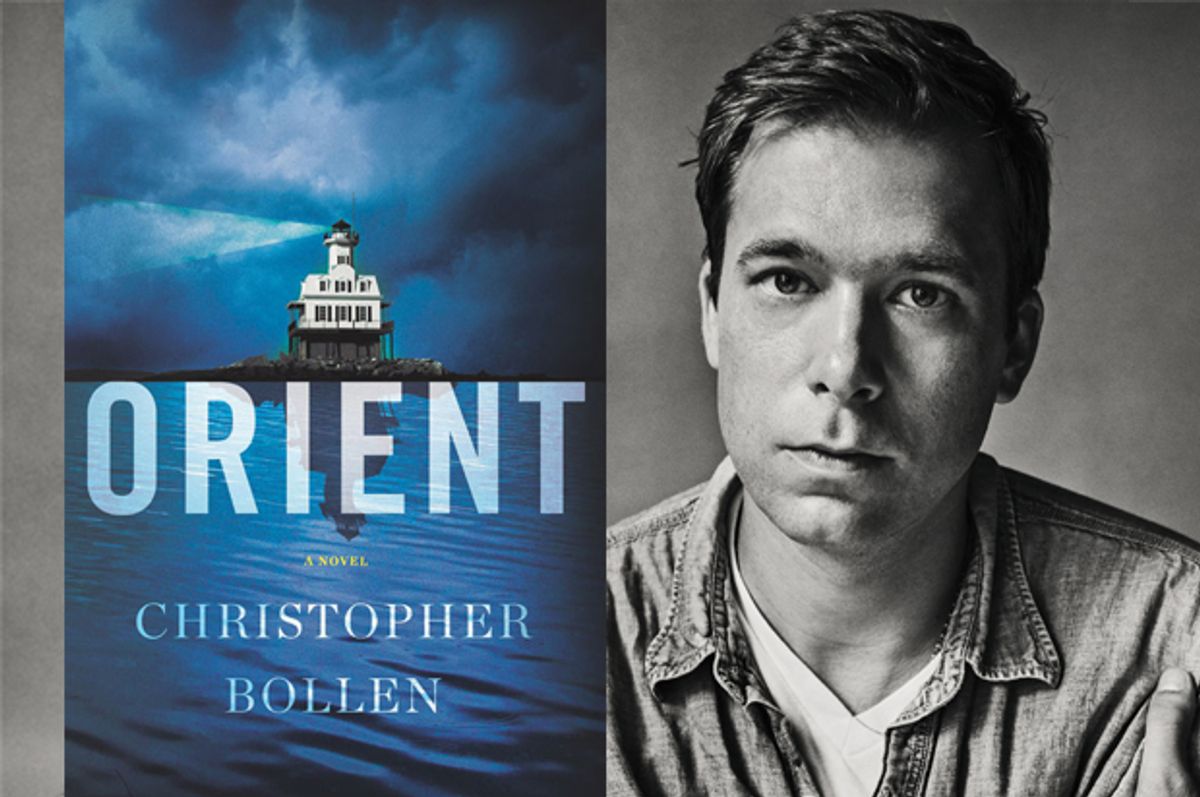

Christopher Bollen has perfected the art of the interview in his conversations with such luminaries as Renata Adler, Toni Morrison, Joan Didion, Brad Pitt, Gore Vidal, Michael Stipe, Eric Fischl, Salman Rushdie and Robert Altman. So he knew what he was getting into when he submitted to questions about his dark literary thriller “Orient.”

Bollen is editor at large for Interview magazine, and according to a writer friend who knows him, “one of the nicest guys you’ll ever meet.”

That might surprise readers of “Orient,” where nice behavior is in short supply. It’s about a real town on the North Fork of Long Island, but the tale is entirely made up from Bollen’s lively imagination. It’s rich in setting and characterization, but it’s also a page-turning whodunit in the mode, as I suggested to him, of Agatha Christie.

Critic Jake Kerridge, writing in the Telegraph, said in “Orient” Bollen conveys effectively the claustrophobia of a community so stiflingly tight-knit that its residents might plausibly commit murder rather than have their peccadilloes exposed to their neighbors.

Bollen spoke to me about the art and craft of the murder mystery, how interviewing Didion and Mailer became his MFA, and about how shepherd's pie isn't always what you think.

One of the things I loved about the book was the setting of Orient, a formerly glamorous village on the North Fork of Long Island, with its long-simmering feuds and allegiances and complex histories. A place where on the last day of summer, the arrival of a stranger is news. It allows you to create tension through gossip – through how the village itself views the Muldoons, Beth, Mills and then the trail of dead bodies that ensues.

Is Orient based on a town you’ve lived in?

I’ve never lived in Orient, although I have spent a lot of weekends out there over the years, even before I began writing this novel. Artist friends from the city started renting and buying houses out there as retreats back in the mid-2000s, and at that time the North Fork was a pretty unknown animal. Most New Yorkers headed to the South Fork of Eastern Long Island, to the Hamptons, and ... well … that had become its own beast. But one of the things that struck me when I went out to Orient was how close it was to the city and yet how tranquil and untouched it was in many ways. It did indeed remind me a little of the Cincinnati suburb of my youth, although much more rural and, obviously, heavily influenced by its location on the sea. I found out later that a lot of the houses in Orient were actually built by shipbuilders and that’s why they look a bit different than the houses farther inland.

But absolutely that tension through old-fashioned gossip and neighborly observations has always interested me. Especially if it’s going to have an element of a murder mystery. I’m not really all that interested in the science of crime à la "CSI." I’m much more fascinated in how crime sends shockwaves through communities and ruptures and transforms their sense of themselves and each other. So Orient was an ideal, isolated community—a sort of idyllic petri dish—in order to set a series of terrible events.

I liked, too, starting the book on the last day of summer when the seasonal residents leave and the year-round folk are left. It narrows the cast of characters, and in a murder mystery, the possible suspects. I was reminded of the Agatha Christie novels I’d read on summer vacations as a kid where all the suspects live in close proximity and I’d change my mind over and over as to who’d done it. Was that the idea?

Yes! Absolutely. I’m thrilled you felt a little Christie in the story, because I was thinking about her a lot over the years I was writing Orient. I, too, was an Agatha Christie fan as a kid—in fact, she might have been my gateway drug into a life of constant chain-reading. Those Christie novels were my first literary passions. I remember basically going into lockdown when reading "Ten Little Indians"; I could do nothing else until I finished it.

When it came time to write "Orient," I took some of the qualities I like in a Christie: namely a whodunit, which is really rare these days. Most mysteries in books and on TV are police procedurals—you follow the officers toward the killer and it's more about the officers than it is about the ultimate criminal. But what Christie was so good at was implicating the reader in the narrative thrust; you were working with her to solve the crime and you were actually also working against her because you knew she was trying to stump you (and in this sense there is a correlation between reader/writer and detective/villain). It’s not a passive form of reading.

That said, Christie and I have very different styles and very different intentions. But I like claiming her as a model. I think there’s this sense that if you are writing literary fiction you can’t touch genre — or if you do touch it you have to overdo it, always winking and nodding the whole time. But why can’t you take the parts you want from everything you read? Certainly I’ve learned wonderful descriptions from magazine items and I’ve even learned ways of describing clothes from fashion magazines.

I was also reminded, of course, of "Jaws," as the first body is pulled from the sea, and as locals think about plummeting property values, and as we learn that a main character has the last name Benchley. Did that movie have a big impact on you? It did for me.

I never read "Jaws" and it didn’t occur to me at all when naming a character Benchley that it carried any reference to the author. I knew a person with that last name — not Peter Benchley — and I always liked it. But I can’t help wondering if "Jaws" got in there subconsciously. That film, oh man. I watched it the summer of '81 or '82 when my parents went to Europe and dropped my older sister and me off at our cousins who lived in the middle of a cornfield in Indiana. And they had a subterranean den and it was later afternoon, before sunset, but getting shadowy, and I sat in that dark basement den — I must have been 6 or 7 max — and watched "Jaws" and I was so frightened I walked as quietly as I could up the steps, out the front, and into the cornfield (which would later frighten me when I saw "Children of the Corn"). But I think about "Jaws" a lot. It’s a brilliant film and I think runs like a scar through the childhood brains of our generation.

There is a very realistic and riveting hunting scene. I wondered how you managed to write it with such authority as a longtime magazine editor living in the lower east side of New York.

I’ve never hunted. Not once. I couldn’t kill a deer (although they do cause a zillion car accidents and are spreading Lyme disease by the minute). But I do know a few hunters. My sister’s boyfriend is a deer hunter (as I discovered after eating a shepherd’s pie one Christmas and then realized it was recently gunned-down venison). I learned about long bows just by talking to him and by going to hunting stores and holding them. But, really, I just made it up as I was writing the scene. I’m glad it’s convincing. It felt convincing to me when I wrote it, and I tried to get the legality right—no crossbows, no air horns, no night hunting. But you know when you touch down on a subject that has long been a blind spot, you do wonder if a real hunter will read that chapter and think, “This writer has never shot an arrow once in his life.”

A lot of the beneath the surface tension in the book revolves around political and ethical battles that have to do with conservation (Bryan Muldoon maintaining that it’s a "conservancy" meeting and not a "conspiracy" meeting) and the last vestiges of genetic testing at a place you call Plum Island. It’s a town where car tires are gashed at night and where the gadflies can wake up dead. Outside of the occasional Obama sticker, the politics are local, and despite the proximity of New York, pop culture rarely seeps in. Was this intentional?

Yes, it was. I know I’m supposed to have the young characters constantly on Snapchat and Instagram and every adult is falling asleep at night to a Netflix marathon. Some writers do this pop-cultural intrusion so well, but I don’t think it’s any more required of a character than describing every time they go to the bathroom. Sure, technology needs to factor in a contemporary novel. People need cellphones and laptops and Facebook pages, etc. But nothing dates a book like name-brand apps or trends. And I honestly think it’s gotten to a point where the “teenager constantly on their iPhone” is now replacing “precocious teenager who looks like a mature 15 but acts 40” in typecasting. But also Orient isn’t the city. I don’t think people who intentionally have left New York to get away from the constant noise have to traffic in that electronic noise when they’re in the country. I know it sounds like a horror-movie cliché, but cellphone service is still very spotty out there.

I loved the old houses in the book and the way characters move through them like archaeologists. You say here, "It was the fate of most household items to linger on after their owners, offering accidental clues to their hopes and distractions." I found that line very poignant. It reminded me of all the evocative objects in the house at the start of "Moonrise Kingdom," the Wes Anderson film. Can you talk about that aspect of the book?

You know, I wrote that before my father died in 2012 but it rings true to how I felt when we were cleaning out his office and closets a few months later. There is a sorrow to items — more so the smaller ones — that have lived beyond their owners and point and prompt and suggest who was there but don’t fill in the picture. They are haunted in a way, but also not haunted enough—if that makes any sense. Inheritance is a big theme in "Orient." A lot of these houses are ancestral, passed down and down, and some of the owners feel the obligation of keeping them along with the prison of keeping them. I myself have never owned a home. I left Ohio and went to New York for college and while I’m not Mills, the young drifter in the story, I do feel a sense of rootlessness, of always renting. There is a part of me that craves an old house like the ones in Orient.

Beth has an ambivalence toward so many things – her artwork, which she’s approached with seriousness and then damaged. And then there’s her pregnancy, which she seems hesitant to entirely acknowledge. With Mills she’s drawn in without entirely knowing why. What do you think binds these two characters?

They are both lonely — the consummate insider (Beth, who was born and raised in Orient) and the absolute outsider (Mills, who is an orphan from the West). And yet from those two extremes both are radically unsure of their place in the village, of whether they want a home or don’t. I was interested in Beth’s reticence with her art and her wanting to start a family because it seems to me that women are never really allowed to be undecided, to change their minds, to say, actually, no, I don’t want this after all. (Men don’t have it much better but they do have a bit more freedom in that department.)

It occurs to me now that I sort of worked off a familiar pairing: the gay man and the straight woman as instant friends. Except, to me, neither Beth nor Mills follows that typical track. Like most real friendships they mimic other relationships in moments: mother, son; boyfriend, girlfriend; protector, innocent. But I really believe in their friendship. They both have too much to lose and they learn that they can trust each other.

What are the challenges of building a whodunit? Did you know all along who did it, or were you wondering along the way? I sensed your pleasure in leading us down one path and then the next, guessing all the way.

This is what I learned in writing a murder mystery: You as a writer aren’t solving a crime; you are preventing the reader from solving a crime. Much of the work felt like magician work: sleights of hands, distractions of the eye, only to reveal a quarter here and there appearing from inside an ear. It’s a lot of work, but I really enjoyed the fact that it had to keep me on my toes. And occasionally when I felt like I was digressing too much or becoming long-winded, I thought, “You have to kill someone now!”

I wrote "Orient" pretty much in the order of its final form. And I had an inkling who the killer might be, but I didn’t know how or why. I allowed myself to discover that as I went along. (I really felt it would be too stale if it worked like rendering a blueprint; some of the twists and turns of the book might be because I’m twisting and turning, trying to figure out what’s going on.) But I also allowed myself to change who the killer was if, say, on page 200, a better character came along. So I tried to give myself freedom. It’s a risk: What if you build the suspense and the murders and then you can’t figure out why the hell any of your characters would be doing this? But I think it prevents a kind of over-calculated construction.

How much of your work as a magazine journalist and as an editor at Interview did you draw on in the creation of the book?

I didn’t get an MFA in writing or a master’s in English. I stopped with a BA and went to work. So in many ways interviewing artists and writers and directors over the years has been something of my graduate school. I learned a lot about the artistic and creative process simply by listening to some of my heroes, like Norman Mailer or Joan Didion. I took what they said and stored it away.

Also, all of these years of interviewing and transcribing and assembling Q&As — Interview magazine-style — has made me a pretty decent dialogue writer. I feel like Interview prepared me for a life of screenwriting, because I can do voices for hours. The funny thing is, I think I prefer writing description. Too much dialogue without any description in a scene, and I often worry I’m phoning it in.

Shares