A wordy headline in the New York Times Magazine recently caught my attention: “Distressed jeans turn punk rock’s battered bad attitude into a commodified style for those with the social capital to dress in shreds." Dressing in shreds comes courtesy of Levi’s “Destruction” brand.

While consumer trends tend to make anything chic sooner or later, there’s a deeper story here, one that takes us back a century to that cataclysmic event, the Great War.

The globe now seems mired in wars, endless wars, none of them “great,” but relentlessly destructive, spewing out refugees in all directions, destabilizing borders and spawning fresh outbreaks of xenophobia. With all that mayhem unleashed in Syria or Somalia, Iraq or Afghanistan, why would upscale designer jeans brandish a label like Destruction?

The answer goes back more than a century to the phrase that provided me with a title for my history of Dada, "Destruction Was My Beatrice." It was a confidential disclosure made by poet Stéphane Mallarmé to a friend, indicating that his muse (Beatrice having already been claimed by Dante) was a force of negation.

Now, this Frenchman was hardly a paragon of incivility. He was neither bohemian nor anarchist. He was a modest schoolteacher with a wife and daughter who happened to have interesting friends (Manet, Whistler, Debussy), convinced that the divine mission of poetry could not subsist as a species of civil service. Destruction, for him, didn’t mean bellicose defiance of the status quo, it meant leading by example as he purged his poetry of everything familiar, agreeable, even comprehensible. His quest culminated in "Un coup de dés," its words scattered across the page like a star chart.

This sort of destruction is prelude to renovation, like remodeling a house. A comparable spirit of creative disavowal emerged with more force—and flair—under very different circumstances several decades later in the midst of the First World War. In a small artist-run cabaret in Zurich, a group of exiles embarked on a dizzying program of unfettered performances night after night in 1916, their creative abandon unleashed by disgust for the ongoing war and its deadly toll. The cabaret’s founder, Hugo Ball, said the combatant nations “cannot persuade us to enjoy eating the rotten pie of human flesh they present to us.” With grim determination, Ball and his compatriots flung themselves into their performances like the boy in Maurice Sendak’s book: let the wild things begin.

Even before the war the arts had disturbed the peace courtesy of the cunning aggression of Futurism and the taunting primitivism of the Expressionists. The traditional consignment of artists to bohemian enclaves insulated them from the general public to a certain degree, so when these and other avant-garde movements adopted the demeanor of public pests it made an impact—Dada most of all. For the Dadaists recognized that the social fabric was rotten to the core if purportedly civilized nations could consent to the wholesale butchery of trench warfare, routine as a commercial slaughterhouse.

The escapades of Zurich’s Cabaret Voltaire have become legendary, and are routinely associated with irreverence and aggression. Typical is a brief profile in the Wall Street Journal earlier this year, a contribution by Jovi Juan to a hundred themes commemorating the centenary of the Great War. Citing Hugo Ball’s wordless poem “Gadji Beri Bimba,” Juan characterizes it as “a literary work designed to mock, undermine and even destroy the very form it was rooted in. From that moment on, art no longer needed to please, it could offend.” That’s a bit much, given that Ball’s poem drew from his immersion in ancient Gnostic magical formulae, and after his performance he felt himself possessed by nothing short of a religious awakening. He spent the rest of his life as an Alpine saint, a devout Catholic, writing histories of the early Church.

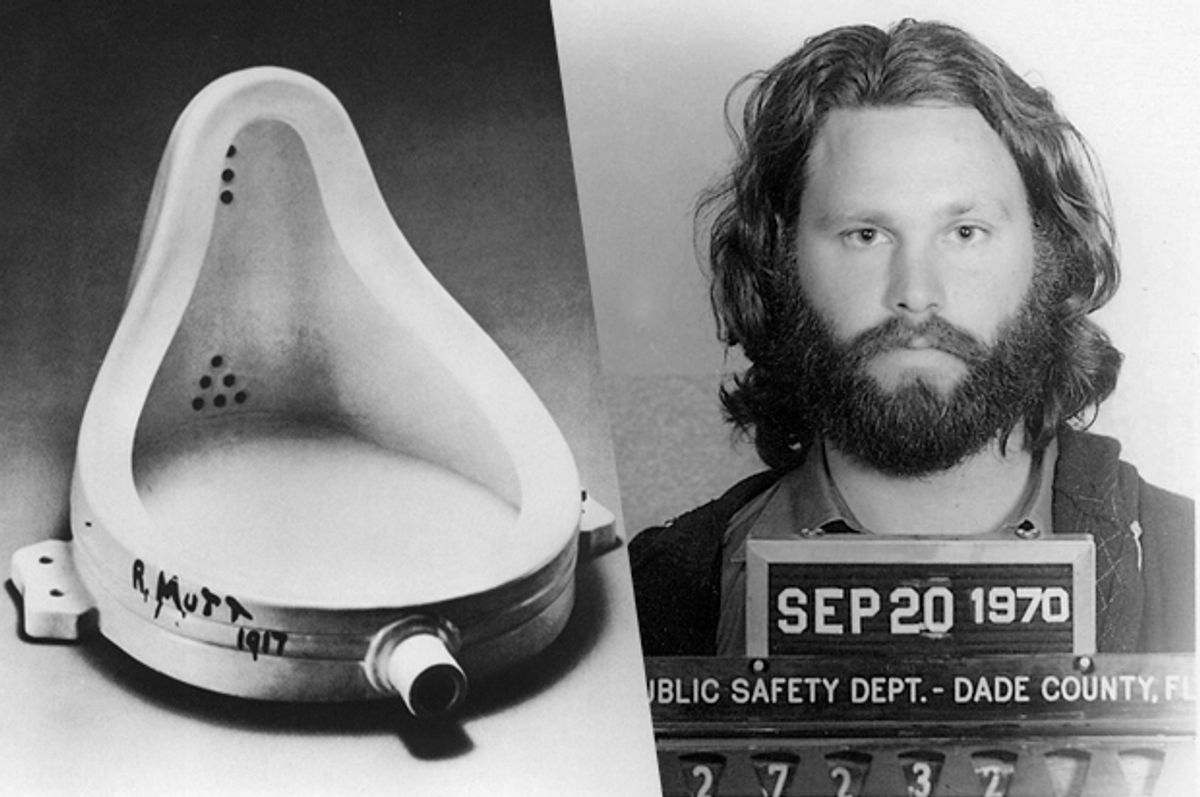

There’s a grain of truth, however, in Juan’s presumption that destruction had much to do with Dada. Ball and his friends denounced the role of journalism in promoting the war and fanning the flames of nationalist xenophobia during the years of combat. We witnessed something similar in this country in the wake of 9/11, when the press contritely swallowed the Bush administration’s claim that an invasion of Iraq was a plausible response. The Dadaists had the audacity to realize that the language of the press and the politicians was not a world apart from art: Any utterance has political implications, even if not intended. So they set up their own advertising agencies, and had a global impact simply by making certain assertions. Most famously, Marcel Duchamp claimed artistic status for commercial products, like a urinal and a bottle rack. It was, as the saying goes, the thought that counts.

Hot as it raged in Zurich, Berlin, New York and Paris, the embers of Dada were all but snuffed out by 1923, yet its influence would persist throughout the 20th century. The cut-up methods Dada pioneered in the arts of collage and photomontage, along with its fertile repurposing strategies, are alive and well today in the sampling procedures of hip-hop, the rapid cutting pervasive in visual media, and above all in the ungainly sprawl of the Internet, where social media sites have unwittingly replicated Tristan Tzara’s zany proposal for creating poems by drawing words and phrases out of a hat, with his startling suggestion: “the poem will resemble you.”

Dada gave art an attitude, and in the process obliterated the notion of art as a sanctuary, a place apart for sensitive souls. “Destruction” jeans are a reminder that attitude can thrive anywhere, and when it does it carries a faint whiff of artistic credibility, courtesy of Dada. Would the Dadaists care? Even in the '60s the aging Dadaists were skeptical of “Neo-Dada” phenomena like Fluxus. They had emancipated art from house arrest, as it were, letting it loose in the world as a force bouncing off other forces. Destruction was the price of contact. With art now in the public eye for the colossal sums fetched at auctions, maybe it’s time to recall the subversive force of Dada, for which the price is never right.

But has the force of Dada’s irreverence been irretrievably co-opted by market forces? If the answer is yes, it means that the whole world has been swallowed up in the dark underbelly of commerce. What Dada continues to offer is the perennial afterthought to any totalizing picture: forget the quixotic dream of a renegade gunman duking it out with The Man against all odds. In the belly of the beast, the survivors are those who escape notice, or figure out how to make the notice they get leave them time to slip off into the dark unseen. Now that’s something we can learn from the admen, the madmen, of Cabaret Voltaire.

Shares