There is guitar on this album. In fact, there is some very impressive guitar on this album, to go with the great drumming and singing. But make no mistake: Fields was all about the keyboards. It’s clear from the opening moments of the first song that Graham Field’s Hammond organ is the star of this show.

Field was never one for traditional guitar-based rock arrangements, opting instead to forge complex swirling compositions the old fashioned way – with all ten fingers. In his songwriting I sense a musical restlessness that prevents him from treading over the same ground again. No two songs on this album sound even remotely alike; it is all over the map, in the best possible way.

I contacted Graham Field to discuss the formation of the band and the recording and release of “Fields.” The following has been edited lightly for clarity and length.

Before Fields, you formed the band Rare Bird.

Yes. I was playing a lot of jazz piano in pubs at weekends and felt frustrated that neither jazz nor most popular music was doing or saying quite what I wanted. So I advertised in “Melody Maker” for like-minded people and electric pianist Dave Kaffineti answered the ad. Dave and I started jamming on my compositions in the front room of my flat in Battersea and the sounds of my Hammond organ and his Hohner clavinet got so big and beautiful and so orchestral we just knew we had to add other people to make them come to life on stage. I had been a chorister at Westminster Abbey for five years as a boy, and the massive sound of the huge organ there kept ringing in my ears.

You might know David Kaffineti as Viv Savage (left) in “This Is Spinal Tap”

We did two albums. The first album we did, we were very green. It was almost our first time in the studio – not quite, but almost. And although the material was good, the recording of the organ in particular shows our greenness. In the second album we got a magnificent organ sound, although the actual live sound from the organ hadn’t changed. From then onwards, I felt I really knew how to record the organ and make a big sound with it when I wanted to.

This was a Hammond organ?

Yes, it was a very modified Hammond C3. Very modified. It was physically modified as well, in the sense that it was transparent. It was in a Perspex transparent case, and it was on circular steel tube legs. It looked pretty groovy! (laughs) It had the most amazing Leslie rotating cabinets. They weren’t actual Leslie rotating cabinets, they were specially made for me, and they were about three times the size and three times as loud as a normal Leslie cabinet. And it meant I could make a real Westminster Abbey sound.

You went down from two keyboard players in Rare Bird to one in Fields. Was your mind made up to keep it a three-piece?

Well, to be honest, when it comes down to it, if you find another keyboard player you can really work with, it’s a slightly rare thing. It’s like in classical music, those people that have got a piano duo, they’ll often say, “there’s only one person I’ve met my whole life that I can really play duets with.” You felt things the same way. And David Kaffineti and I, in Rare Bird, we just understood one another instinctively. And you don’t find that all the time. There were loads of keyboard players I could have asked, and I knew that we’d end up fighting. We wouldn’t feel things the same.

There had been no guitar in Rare Bird.

Yeah, we all felt that guitar dominated pop music too much. We also felt that – I felt strongly, being a classical musician – that lead guitar, rhythm guitar, bass guitar and drums was an OK sound for a certain sort of song, but it wasn’t very interesting, and we were rebelling against that completely. We weren’t the only people – King Crimson were rebelling against that, Emerson Lake and Palmer were rebelling against it, and Procul Harum were most definitely rebelling against it.

With Fields, with Alan Barry playing a double-neck bass-slash-guitar, you kind of added half a guitarist…

Yeah! Well… he’s more than half a guitarist, he’s a monster guitarist! (laughs) But he’s very tasteful. He also had a voice that I really liked writing for. And having written for the big voice that Steve Gould had in Rare Bird, it was quite interesting to write stuff for a tenor like him. I love writing for the voice – I still do today. I love writing for choirs, solo voices, things like that.

Can you tell me about the instrument that he played in Fields?

Yes, it was a white double-neck Gibson and it looked beautiful. It sounded beautiful, too. Bass guitar and lead guitar. I can’t tell you much more than that because I’m not a guitarist myself! But I remember his joy when he first saw it. He just couldn’t believe that he was going to own and play such a gorgeous instrument.

Well, your keyboard parts had such a dynamic range, it must have been nice to have him able to switch from bass to guitar and back, depending on where you wanted to play.

Yeah, I used a lot of keyboards at the time. Synthesizers were in their infancy, and there was only one that was any good – Moog synthesizers. And it seemed to me there was only one sound on that that was good, and so I steered away from that, but I had two keyboards on top of the Hammond C3, which meant I could get a tremendous range of sounds. I had a Hohner clavinet… and I can’t remember what the name of the other one was, some funny little thing I found, and each one made all the sounds the other ones couldn’t.

How was it recording that first Fields album? Was it fast or was it tedious?

It was careful, because we wanted to be very good, but it was certainly wasn’t tedious. You could say that there was quite a bit of ability in that studio. The drumming was lovely, the guitar playing was lovely, and hopefully the keyboard playing was reasonable. It flowed pretty well.

Would you set up and record pretty much live, or were there a lot of overdubs?

There were a lot of overdubs, because we wanted to make a really good album. We didn’t want King Crimson looking down their noses and saying it sounds like a demo! (laughs)

Did you tour a lot for the album?

We would have toured a lot more had we had a better agent, but we did all the work we were offered, so yes, we played all over Europe, and we played a few gigs in England. But we knew that Europe was where we wanted to crack it first and foremost, because [the Rare Bird single] “Sympathy” was still hanging around in various countries at number one.

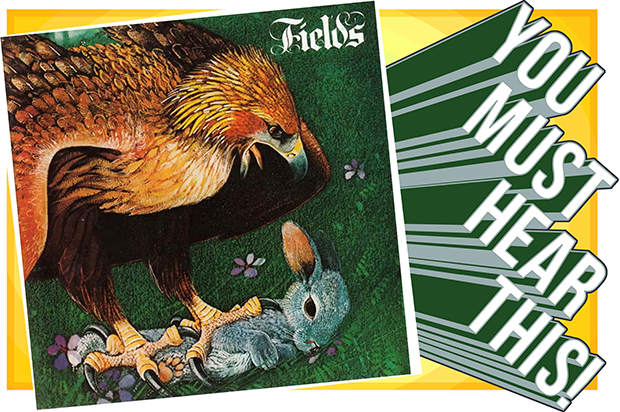

Let’s talk about the album cover, by the artist Colin Paynton. I happen to love it – it’s truly bonkers.

Look, it was a good, grabbing cover. But, the label, who haven’t got the world’s most imaginative ideas at the time, thought, “what anybody in rock has to do is to look hard.” So all of the pictures they took of us were holding onto bars and things like that. As if we were caged animals, almost! So that we looked hard, you see. And then, that cover was – it wasn’t the gentleness of a field, it was about the only vicious act that will ever take place in a field. And I thought, “how typical of them, that they feel they have to do that.” However, having said that, the artwork was tremendous! It was a work of art, I just didn’t care much for the subject.

What do you remember about the actual release of the album? Did CBS get behind it?

If I’m honest, what I really remember is that when [Rare Bird’s label] Charisma, the small family label, issued an album, you felt a feeling of excitement. When a big company issues an album, I’m not sure you feel that same feeling of involvement and excitement. It’s as if you’ve had something you’ve made hung up in a window at Marks & Spencer. You don’t feel that a boutique which specializes in the certain sort of clothes has said that what you’re doing is special, and everybody that likes that sort of thing is going to come here. What our music needed was a manager and a record company that really believed in the music and understood it, and Tony Stratton Smith at Charisma was very good at understanding it. Frankly, at CBS at the time there were some very nice people but there wasn’t the quality of thinking.

Graham Field currently resides in Lytchett Matravers, in Dorset, England, where he is working on a medieval chamber opera called “The Treasure of The Knights Templar.” He recently oversaw the release of Fields’ second album, “Contrasts: Urban Roar to Country Peace” on Cherry Red Records. The album was recorded in 1972, but was shelved by CBS and was never commercially released until this year.

Previously: