When my cell phone buzzed, I was watching Jon Stewart. My anxiety immediately kicked into overdrive. It was summer; it was night; and the caller ID read “Big Mike.” These were all signs of the perfect storm. Big Mike—or Elder Michael Cummings—had once been a gang member and drug dealer; he still played multiple roles in Watts but now worked as a combination tow-truck driver, activist, and street interventionist. More than anything, he was a man devoted to keeping the peace in Watts. He responded to any street violence with a bagful of strategies for de-escalating tension and preventing retaliation. I dreaded answering his call, knowing something major—perhaps tragic—had probably occurred.

“Doctorjorjaleap,” he began, running my official title and first and last name all into one word. “You’re a master social worker.” This was clearly a question disguised as a statement. While I knew a great deal about his life and work, when it came to describing my job, Big Mike was on shaky ground. He was aware that I taught at the University of California at Los Angeles and that my writing had something to do with gangs and public policy, but beyond that he didn’t quite know what I did. Most days, neither did I. Officially, I was a combination researcher-writer-activist. As impressive as this looked on paper, I was less a Renaissance woman than an anthropologist with a perpetual identity crisis. Nevertheless, I possessed the necessary MSW and had been on the faculty of the UCLA Department of Social Welfare for over twenty years, so I could in good faith answer yes.

“Okay, good. We’re starting a fathers’ group at Jordan Downs and we need a master social worker. Can you be our social worker?” I exhaled. Nothing tragic had occurred. Despite the sense of relief, my heart kept pounding. What I was experiencing was pretty much the professional equivalent of bumping into an old boyfriend. Watts—the most crime-ridden community in South Los Angeles—and I had broken up long before, and I had moved on to work with gangs in other settings throughout California. But, deep in my heart, I still carried a torch for three violence-torn public housing projects in a corner of South Los Angeles: Jordan Downs, Nickerson Gardens, and Imperial Courts. In my rush to get back to the streets of Watts, I answered yes with such force and enthusiasm that Big Mike was taken aback.

“I would love to!”

“Okay, okay, slow down. We’re gonna see if this even happens. Can you be at Jordan Downs next Wednesday night? You, Andre, and me—we’ve gotta have a planning meeting.”

“Okay. I am excited. And I’m gonna slow down. But you need to tell me what this is about.”

“We’re gonna get a group of men together to meet and talk about fatherhood. We’re gonna try to help them to be good fathers to their children. You know, a lotta these guys have been locked up, so we are gonna help them after they get out of prison or support them if they’re tryin’ to stay out of prison.”

Despite my enthusiasm, I felt wary. Somehow this need for a social worker smacked of institutional accountability—someone, somewhere was trying to cover his ass.

“Who’s organizing this, Mike?”

“It’s all part of something called Project Fatherhood. Do you know Dr. Hershel Swinger?”

“Yeah, I know Dr. Swinger. I worked with him.”

“See, I knew you were the right one to ask. Dr. Swinger is helpin’ us to set up Project Fatherhood because he wants us to teach men how to be good fathers.”

Whatever Big Mike might be talking about, if Hershel Swinger was involved, it had something to do with strengthening families— an approach Swinger and many others believed in passionately. This was not a Trojan horse trotted through the community gates by social conservatives, promoting “family values” while sneaking in hopelessly discriminatory legislation. Instead, it was a school of thought that advocated turning traditional ideas about families—particularly poor families—upside down. Rather than searching for dysfunction, mainly among marginalized and impoverished families, this approach identified and built upon the families’ strengths. Instead of wishful thinking, it offered a nuanced view of families bound and gagged by a system that failed to understand the complexities of their lives. Early in my career,

I had quickly learned that every family I encountered—even the most troubled—invariably had positive characteristics somewhere, operating in some ways. None of this knowledge came from published research.

I knew this from my Rolodex of shot-callers, people who would have made great attorneys or finance experts; they were the ones who “provided” for brothers and sisters and aging grandparents. I had “case managed” too many drug dealers who multitasked and orchestrated the exchange of cash for product, even as they responded to phone calls from multiple baby mamas. They picked their kids up from school and took them on camping trips, all while they were dealing meth or heroin or marijuana. The picture was complicated. Their lives and their families were complicated.

This whole notion of “family strengths” went against the helping professions’ past conventional wisdom, which had been all about pathology. Traditionally, social workers and therapists were trained to identify problems and develop plans to solve them. I practically had been breastfed this worldview in graduate school, from Daniel Moynihan’s observations on “black matriarchy” to Oscar Lewis’s analysis of the “culture of poverty.” The focus on deficits reinforced the idea that poor families were dysfunctional, and it mainly implicated families that were African American or Latino. These discussions, both inside and outside of the classroom, contrasted with explorations of other ethnic groups—Japanese, Chinese, or other Asians—whose families were often portrayed as integrated and strong. Of course, the era gave rise to the smug aphorism “family is just a synonym for dysfunction,” with its implied message that professionals knew what families needed, and that they were in the best position to correct things. Even as an inexperienced and naïve social worker in the 1970s and 1980s, I was uncomfortable with this approach. The chain of cause and effect didn’t make a lot of sense to me; pathology involved multiple factors, including biology, history, and economics, much more than it did problematic families. Despite its shortcomings, the perspective guided most social work interventions and approaches, until the idea of family strengths emerged in the mid-1980s.

Changing the dominant mindset was not easy. Resistance was everywhere, including among thought leaders who emphasized a combination of marriage, chastity, and religion as the best and only answer to the struggles parents and children faced. And then there was the challenge of just how to use hidden talents and strengths to solidify families. All this percolated as I was making changes in my own work, turning from practice and training to research and evaluation. Strangely enough, my new work brought me into direct contact with Dr. Hershel Swinger.

I got to know Swinger when I worked as part of a research team led by Dr. Todd Franke evaluating the effectiveness of the Partnership for Families (PFF), a child-abuse prevention initiative dedicated to strengthening families. Swinger, an African American professor with a PhD in clinical psychology, emerged as a voice for family strengths. He was one of the key designers of the PFF program, sponsored by First Five LA as part of its comprehensive state effort offering programs for children during their first five years of life. Everyone in the Los Angeles social work and human services community knew Dr. Swinger; his work commanded respect. It went beyond examining family strengths to shed light on how children dealt with the trauma they suffered as a result of community and family violence. In particular, Swinger’s work illuminated how children with absentee fathers suffered more anxiety and depression, and experienced higher rates of drug abuse, school dropout, and—the most common item on the urban curriculum vita—involvement with the criminal justice system. What I didn’t know until the call came from Big Mike was that Swinger had been talking about fatherhood long before it became a rallying cry of politicians and policymakers.

In 1996, Swinger began organizing and implementing Project Fatherhood. The program was structured to reduce child abuse, neglect, and involvement with children’s protective services by supporting and strengthening high-risk, urban fathers. Swinger’s emphasis on the critical role of fathers eventually attracted national attention from both Republicans and Democrats. After the program received a $7.5 million federal grant in 2006 under the Bush administration, Swinger oversaw its replication at fifty agencies throughout Los Angeles County. In 2010, the Obama administration recognized Project Fatherhood as a “model program.”

But I knew very little about this. When I told Big Mike I would show up for the planning meeting at Jordan Downs, I had only a rough sense that I was joining an effort that included work in child abuse prevention but encompassed a great deal more. It was an undertaking that went beyond issues of gangs or violence—right to questions of fatherhood, male identity, and families’ experiences of both pain and loss. I wasn’t thinking too deeply about any of this. All that played in my head was the mantra I want to get back to Jordan Downs. I want to go home to Watts.

This was a pretty peculiar desire. Most people—whatever their color—looked at me skeptically when I brought up the subject of Watts. “You gotta remember, Watts is different,” Kenny Green said while we ate lunch, when I mentioned that I was returning there to potentially co-lead some sort of fatherhood group. Kenny had been a gang interventionist for seventeen years, guiding and at times protecting me while I worked in the streets.

“I know, but I think this program sounds like a great idea.”

He shook his head and warned me, “You keep forgetting—it gets crazy there in a totally different way than anywhere in Los Angeles, even South Los Angeles.” I understood his cautionary tone. For most people,

Watts was synonymous with riots, poverty, and danger. But for me it was where I had come of age as a social worker and fallen in love with the man who would be my first husband, and where I had felt adopted by black families living in the projects, people who told me, “You just a skinny little white thing who don’t know much. Hush up and listen.” Watts always felt like home to me. I wanted to help with whatever was going on with family strengths and Project Fatherhood.

In truth, I was ill-equipped for the task. I had come to the game of parenthood late with the adoption of my daughter, Shannon, and I possessed a boatload of insecurities about my relationship to her. Fatherhood? I had enough trouble being a mother. The entire arena of fatherhood was pretty much alien to me. The relationship I was building with my own father had been cut short when he died of cancer while I was in college. For me, fatherhood was invariably associated with masculinity, wordless bonds, and—more than anything—loss.

These associations were all reinforced in 2008 when I started observing the work of Father Greg Boyle at Homeboy Industries, a Los Angeles–based gang intervention agency. There I quickly realized that, for the former gang members enrolled in Homeboy’s reentry program, fatherhood was intertwined with a deep wound and profound yearning.

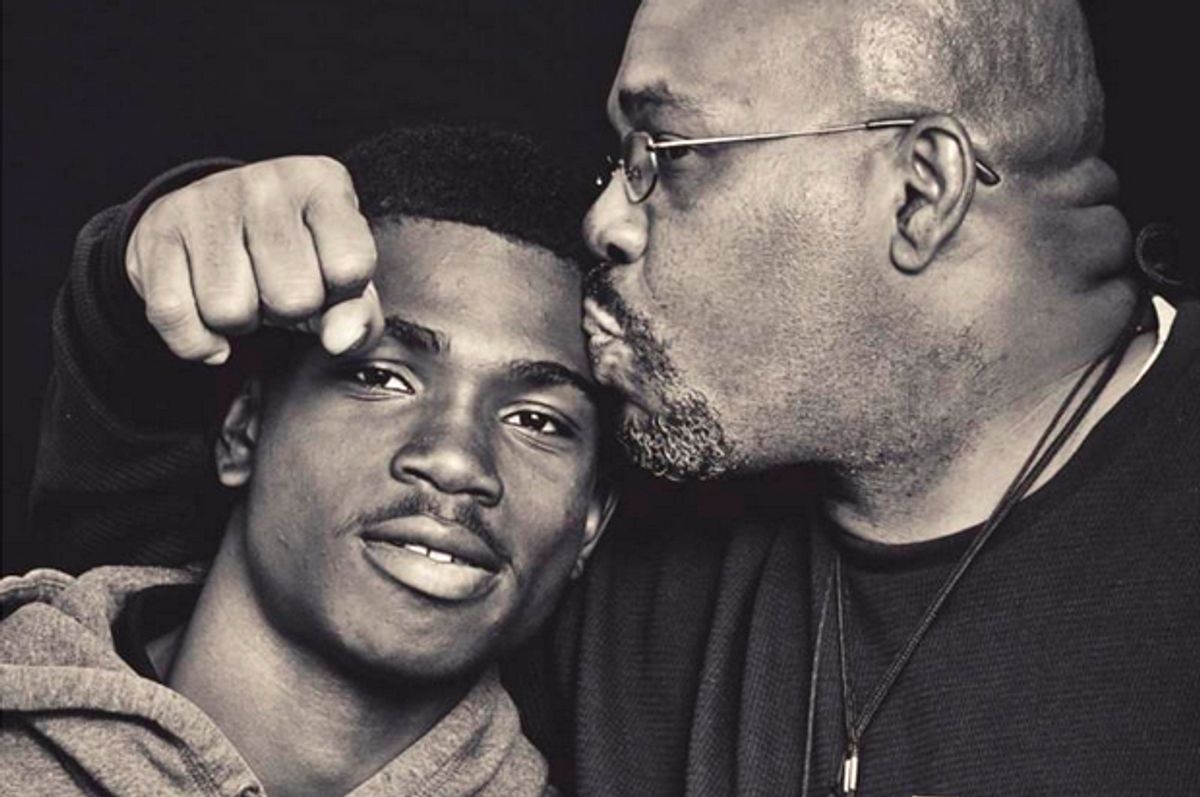

Greg was very clear about all of this. He told me over and over again, “There is a hole in the soul of every homie here—in the shape of their father. Most of these youngsters have never had a father in their life. And they want it. Look at some of the kids you see who come in here—their mothers are doing all they can—but they miss that father, they miss that presence in their lives. Then there’s the homies whose fathers have had long-term drug problems. So even if they’re around, they’re not present, they’re not part of their lives. All these kids want is a father—someone to care about them. They know that’s how life should be. And they want that for their own children. We have to help with that.”

Despite all the attention that Homeboy received for its social enterprise efforts and its work to obtain jobs for program graduates, Father Greg, or “G,” was adamant that former gang members who received only job training, job placement services, or actual employment would not truly heal or resolve their identity issues.

“Any kind of job program has to be accompanied by a therapeutic community, so these individuals can work on themselves, on their trauma and their losses. This is where the hope comes from. Because we know: a hopeful kid never joins a gang or goes back to his neighborhood.” It was clear to me that Greg—and by association, Homeboy Industries—was trying to provide a parenting experience within its walls.

This was integral to the needs of former gang members I came to know.

After five years of being embedded at Homeboy, I came to find their stories achingly familiar. Most had tragic themes. The gang members or homies described fathers who had been incarcerated with life sentences; fathers who had disappeared, abandoning their families; fathers who carried on whole separate existences involving other women and other children; and fathers who overdosed. Familiar, no matter which homie was talking, was an essential longing for a father—any father.

It was a longing Greg answered for many. We would sit in his office and talk after a long day in which men had trailed in to talk with Greg about their eagerness to leave gang life, their feelings of aloneness, and their enduring fears.

“You can just listen to them and understand that, somewhere along the line, they felt no one cared for them. No one cared about them,” Greg mused. “That’s why we have to be here for them. We have to care for them, because we know that our community—our family—is going to trump the gang. And maybe, just maybe, we will stop the cycle with this generation. We can teach them to be the fathers they never had, because that wound is deep.”

I nodded as I listened. In interviews, I had discovered that many times a homie made the decision to leave gang life when he had a child, most notably a son. They were determined to raise their children in safety and repeatedly told me they wanted to see their children grow to adulthood. It was the turning point that changed their lives.

“I never had a dad,” a boy who looked like he could barely shave told Greg. “I wanna be one to my son.” After he left, Greg sighed. “We’ve gotta help him. I buried his father—he was shot and killed before this kid was born. His girlfriend was seven months pregnant at the funeral. The father was a nice kid too. Wrong place, wrong time.”

But he was not the only one. Greg saw many who had experienced similar losses that had never been resolved.

“Everyone longs to connect,” Greg would tell me. “Everyone longs for kinship, for attachment—to belong.” At Homeboy, proof of his words was offered during the hours of operation. For days on end, I watched as heavily tattooed, angry men collapsed when they started talking with Greg. In fact, the angrier the homie, the greater the likelihood of a complete breakdown. Whether fourteen or forty, these men—brown or black—clung to Greg with an affection that bordered on desperation. They unfailingly referred to him as “Pops,” or “my father, G.” He referred to each of them as “my son” and often remarked, “If I were your father and I had a son like you, I would be so proud.” At those words, even the most hardened gangbanger would break down in tears.

Watching their reactions invariably filled me with awe at the depth of their need for that bond. These men—who routinely used guns and dealt drugs and brutalized women and went to prison and had no clue how to father their own children—needed first to be fathered themselves. The depth of their loss and the needs they expressed also implied a question they rarely posed directly, but managed to communicate: How can I ever be a father? Because of Big Mike, I was about to become involved with a group of men who wanted desperately to learn. But as far as I knew, there was no teacher, no guide, and no training manual. I had no idea what I was getting myself into.

There was one thing I knew for certain: what I had learned by watching Greg—about loss, connection, and community—would surely inform what I was going to try to be part of at Jordan Downs. Every man longed for a father. I wanted to get to know the experiences of these men. Did they have fathers of their own? How did they feel about what they had experienced in their lives? And, more than anything, how did that affect the ways in which they acted towards their own children? I knew I did not have the answers, but I was in a place where I might find some. I was going to Watts, where much of the adult male population spent a great deal of time engaged in criminal activity or locked up because of that activity. I was going where there were more “absentee fathers” than there were in any other parts of Los Angeles County.

All of this was on my mind as I was leaving Homeboy Industries after interviewing homies to meet Big Mike at Jordan Downs. As I walked out the door to leave, Keeshanay, a wiry little lesbian gangbanger, intercepted me.

“Where you goin’, Mama?” she asked.

“I’m going to Jordan Downs. I’m gonna have a meeting with Big Mike.”

“Be careful, Mama.” She looked at me more sharply than usual. “It’s tricky down there. I don’t want anythin’ to happen to ya.”

As her unofficial parent of choice, I hugged her close and reassured her.

“I’m cool.”

At that moment, it was hard to square Keeshanay’s anxiety with citywide statistics, which indicated Los Angeles was experiencing its lowest crime rate in forty years. At the county level, the crime rate was the lowest it had been in fifty years. These are not minor numbers with negligible impact. The population of the city of Los Angeles is almost four million, while the population of Los Angeles County nears ten million.

But in Jordan Downs in the past week, there were four murders, all gang related. When Keeshanay tells me things are tricky, I am certain she knows plenty about why the gangs—or neighborhoods—have suddenly turned so violent. But none of this matters. All that matters in this moment is that I am going home. To Watts.

Excerpted from "Project Fatherhood" by Jorja Leap (Beacon Press, 2015). Reprinted with permission from Beacon Press. All rights reserved.

Shares