For a long time, the NME was part of what made British rock music (whether punk, post-punk, alternative rock, indie rock, or whatever) distinctive and vital. Because the NME and its rival, Melody Maker, published every week on a small, music-mad island, its choice of cover and profile subjects had an agenda-setting role. But despite massive influence and circulation – it distributed 300,000 copies in the early ‘60s – the music-paper’s print run is now anemic. And to return to its old numbers, the NME – founded as the New Musical Express in 1952, two years before Elvis Presley recorded “The Sun Sessions” — has announced that it will begin to distribute for free.

It’s not news to anyone that print of all kinds – general, specialty, British, American – has had a very hard time of things for the last decade or so. But to see a publication that was once a kind of holy document – especially to Americans, who typically had to find a very plugged-in record store in which to find one – piled up free at train stations and corner shops feels like a defeat. In fact, it reminds us of nothing so much as U2 (a band that was, after all, cool and original at one point as well) giving away its latest album to everyone with an iTunes account.

The music journalist Simon Reynolds – British-born, now US-dwelling – wrote a wonderful, elegiac piece for the Pitchfork Review. “Imagine, if you can, or remember, if you’re old enough, a long-ago time when music fans had to wait,” he wrote. “Wait for news about music. Wait for reviews that were really previews of music you’d wait even longer to hear. (No teasing tasters, sanctioned streams, or illicit leaks in those days.) Anticipation and delay structured the daily experience of music fandom in the pre-internet era. All music and most information were things you literally got your hands on: they came only in analog form, as tangible objects like records or magazines.”

His story, “Worth Their Wait” continues:

What the music papers I grew up on offered was a concentrated, all-enveloping experience that allowed you to escape from your real surroundings, with all their dreary limitations, and achieve vicarious access to the place where all the action was happening and all the ideas were percolating… In romantic love and in music fandom, absences and delays create the space in which desire grows… In an “always on,” instant access world, the flooding nowness and nearness of everything unavoidably smothers and stifles these impulses. It kills not just yearning, but eventually appetite too.

It reminds me of something Paul Weller said to me last month, about the way rock music has changed since he was in The Jam: “I miss the sense of magic and mystery. Everything is so instantaneous now.”

Contrast all of this with the announcement by the NME’s editor, Mike Williams, on its shift to free circulation:

“NME is already a major player and massive influencer in the music space, but with this transformation we’ll be bigger, stronger and more influential than ever before.

“Every media brand is on a journey into a digital future. That doesn’t mean leaving print behind, but it does mean that print has to change. The future is an exciting place, and NME just kicked the door down.”

Maybe this is the only way the NME can survive: It’s following the same path that record albums, which we used to have to trek to the record store for, have made. Changing technology has made stasis impossible.

The problem is that as things become plentiful, they lose much of their value, and just about all of their romance. It may be that only 15,000 copies of the NME sell each week, if circulation numbers are to be believed. We don’t expect to persuade the folks who set advertising rates, but a handful of dedicated readers can mean a lot more than a huge number of indifferent ones. The fate of publications on the web has shown that.

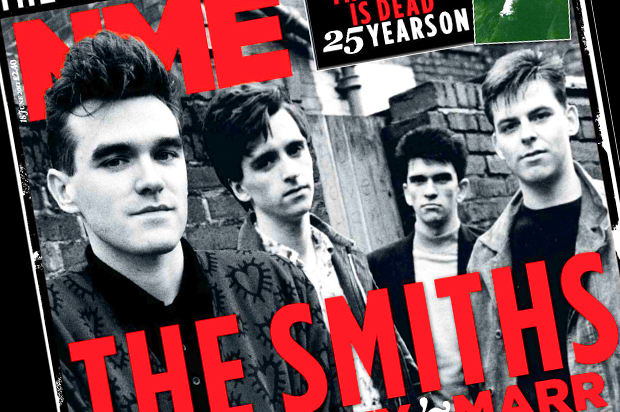

Whether you loved the Clash or The Smiths or Madchester or Massive Attack or Amy Winehouse, the British music papers kept you plugged in to a conversation you had to make an effort to join. Once it’s everywhere – and once it’s about being an “influencer” and a “media brand” — will it matter as much to anyone?