I am on the Number Three train from Manhattan, on my way to see Judy Chicago’s "Dinner Party," now permanently installed at the Brooklyn Museum. Although this will be my first time physically viewing the piece, we have already met. I am heading toward a “this is your life” moment, reconnecting with a childhood guest who had stayed just long enough to drop subversive seeds in the furrows of my young brain and then blow out of town. I’ve been putting off this visit for more than a year, not wanting to discover that I’d been taken in by something that, all this time later, would turn out to be pedestrian or just plain silly.

The Brooklyn Museum sits at the mouth of Eastern Parkway, part of a neoclassical trinity that includes Grand Army Plaza and the Brooklyn Library, where my mother used to walk with her friends to pick up her weekly stack of nurse novels. I too know this route well, from years of visiting my sister or dragging myself to relatives’ simchas in Crown Heights. The Lubavitcher neighborhood where they live begins a scant half-mile down Eastern Parkway. The first clue that you have entered foreign territory is a giant yellow banner hanging from the roof of an apartment building, bearing the image of the late Lubavitcher Rebbe and the declaration, “Long live our Master King Moshiach for ever and ever!” The second is a sign, in high black letters, mounted on the new wing of the Oholei Torah boys’ yeshiva: “Menachem Mendel and Hinda Deitsch Campus.” My great-grandparents.

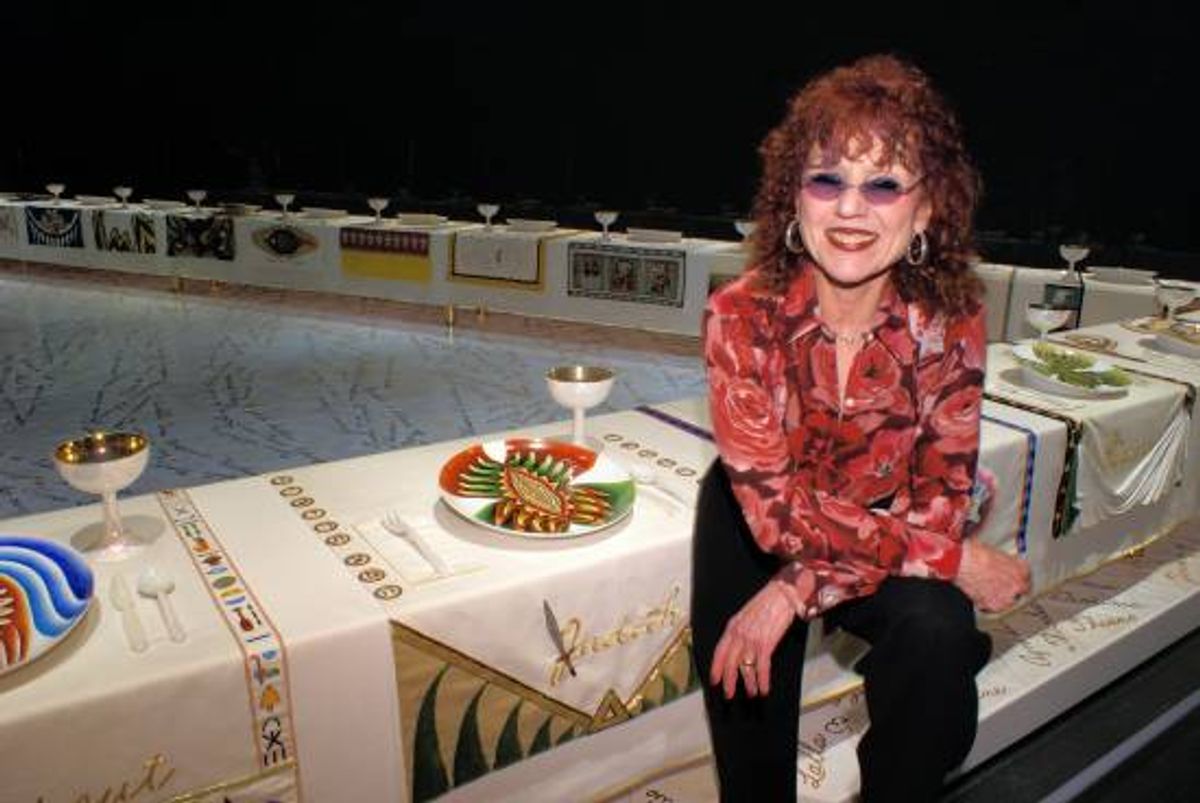

But today I’m not going as far as Crown Heights. Upstairs at the museum, I take my time entering the darkened room (womb?) where "The Dinner Party" is displayed. Then there it is — the iconic triangular table, the 39 place settings dedicated to, among others, Hatshepsut, Boadaceia, Hildegard of Bingen, Elizabeth Blackwell and Sojourner Truth. There, on the white-tiled floor, written in gold, are names of 999 other women whom Judy Chicago had pulled from the crevices of history and transformed into art. I’m relieved and stunned by how beautiful it all is. I peer down at the first plate — Primordial Goddess — and take in the suggestive oval of bright red, ringed by fleshy folds of pink, brown and acid green; it rests on a placemat of deer hide fringed with tiny cowrie shells. The sight of it triggers a memory so keen that my eyes well up and the breath catches in my chest. Suddenly it is 30 years ago in New Haven, my 16th birthday, and my mother’s friend Basha, erstwhile flower child and reluctant Lubavitcher housewife, hands me a large book wrapped in purple tissue paper.

“Your mother will probably kill me,” she says, “but I think you’ll really get it. Her show just opened in San Francisco.”

I accept the package warily. Basha — tall, flamboyant, patchouli-scented — likes to provoke. She watches me open the package, scanning my face for a reaction. It is the exhibition catalog for "The Dinner Party." I examine the cover and thumb through the book, noticing the high ceramic glaze of wings and furrows and wondering if they are what I think they are.

“Thanks.”

Later, I will read the catalog cover to cover, titillated at first by the profusion of vulvas —Emily Dickinson’s lacy labia, the color of strawberry yogurt, are particularly disturbing — but soon enough I’m completely absorbed by the lives of women I have never heard of.

Basha was right about my “getting” it, but wrong about my mother. The zeitgeist had already begun to seep through the tight seals of our Lubavitcher home, mingling awkwardly with the baroque shabbos candelabrum, my father’s volumes of Chasidic teachings, the cholov yisroel milk we shipped in from Brooklyn and the giant portrait of the Rebbe that seemed to glare at me reprovingly from the dining room wall. Although you would never know it by her brown curly sheitel and high-necked, long-sleeved outfits from Loehmann’s, my mother was interested enough in women’s lib to borrow copies of Ms. magazine from my aunt, Danya, who was in the thick of a “rebellious” phase. For married women in my family, this could mean as little as not tucking every stray hair under your kerchief. In my aunt’s case it had also manifested itself in bead curtains, daisy decals on the toilet seat, a “War Is Not Healthy for Children and Other Living Things” poster, a Volvo and feminism.

I discovered the stack of magazines on the floor of my parents’ dressing alcove and proceeded to give myself an education not found in the curriculum our local Jewish day school. Unlike the other secular magazines that came to the house -- Good Housekeeping, Ladies Home Journal, Time, National Geographic, even Vogue from time to time – Ms. was different. The woman’s bruised face on the cover, her shiner a gauntlet thrown down at the world, made me slightly queasy, but it didn’t stop me from opening issue after issue to read about wire hanger abortions, the ERA battle and “the housewife’s moment of truth.” I wondered if my father knew about the magazines.

I managed to get halfway through the pile before my mother caught me.

“Um, those aren’t really for you,” she said.

“Oh? How come?” I asked, even though I knew perfectly well what she meant.

“Maybe when you’re older,” she said firmly, then shooed me out of her room.

When I went back for them later, the magazines had vanished, but a little sleuthing led me to her bed, where I inched my fingers between box spring and mattress until I hit something solid. I yanked out two copies, took them to my bedroom and closed the door.

I was 13 at the time. My mother was 32, pregnant with her fifth, and last, child, and encumbered by an overweening sense of edelkeit—an untranslatable combination of refinement and propriety—that prevented her from voicing opinions that might lead others to tzitz about her. And yet somehow a year’s worth of Ms. had found their way into the house and were searing themselves into my consciousness. So did a copy of Nora Ephron’s "Crazy Salad," which I studied so thoroughly that I could have quoted long passages from memory, had anyone known I’d read it. The book was a revelation. Ephron’s frank and hilarious commentary on such unmentionables as the problem with feminine hygiene sprays, our cultural obsession with breasts and the shackles of ladylike behavior all struck a deep chord with me. My hormones were surging, transforming my body into something I barely recognized, yet casual dating was off-limits. I was inhaling every scrap of current events, literature and pop culture I could get my hands on, knowing that college—forever cemented in the imaginations of Russian-born Lubavitchers as a viper’s nest of Communist iniquities—was not in the cards. I needed a way out. After all, the math was simple: If I married at the same age as my mother did, I had four years left. I had no time to lose.

Orthodox Judaism, including Lubavitcher Hasidism, does not particularly subscribe to the myth of the “delicate sex.” Most of the women I knew were intelligent and highly competent; my two grandmothers had kept their families one step ahead of both the Nazis and Stalin’s purges. And yet, from the time I was small, some unseen hook was dragging me offstage, inch by inch. At 7, I was banished from the men’s section at shul and sent upstairs to join the women. By 10, clothes shopping had become a challenge: In keeping with the rules of tznius, elbows, collar bones and knees had to be covered. And no pants, to avoid breaking the injunction against beg’ed ish, cross-dressing. My bas mitzvah, ostensibly my official entry into Jewish womanhood, went unheralded, with no haftorah in front of the congregation, no flowery speech thanking my proud parents. And once marriage came, my hair would be kept literally under wraps, hidden beneath an expensive human-hair wig or a colorful tichel. Then, with a husband to serve as my community and religious representative, I could finally, officially be relegated behind the curtain. It was no wonder that when I tried to visualize myself married, like my older female cousins, the canvas was blank.

By the time I reached high school, I felt as though my very existence were at stake, do or die. At school, I would confront Rabbi Bernstein, who taught us halacha, Jewish law.

“Why are women exempt from davening? And why don’t they count in a minyan? And why should you thank God every day for not being made a woman?”

Rabbi Bernstein would stroke his beard for a moment and look at the ceiling thoughtfully.

“That’s an excellent question, Chaya. The reason women don’t have to say daily prayers is that they are inherently more spiritual than men, so they don’t need to work as hard to get close to God. And I thank Him for not making me a woman because I get to do these extra mitzvahs for Him. Besides, it’s hard to be a woman – she has the pain of childbirth.”

“That doesn’t really make sense to me.”

“Think about it for a while.”

I tried my father, railing at him that a religion that couldn’t change with the times wasn’t a religion worth holding on to. A man of deep faith and few words, he responded to my outrage with looks that alternated between confusion and panic, a beleaguered shop manager waiting out a deranged customer.

“Don’t be like that,” he’d plead.

And yet I was like that, and fighting the good fight, it felt like all alone. My school friends seemed untroubled by what I saw as the Torah’s repression of women, but then most of them were allowed to wear cute Levi’s and flirt with boys they met at camp or at weekend youth groups. After graduation, they would head for college, while I would be paired off with a nice young man of good Lubavitcher stock, boxed up like a diamond too expensive to ever wear outside.

And then along came Gloria and Nora, hidden from me in plain sight, I chose to believe, by my mother, who couldn’t bring herself to utter the words, “Run as far and fast as you can. Don’t become invisible.” Unable to give me leave, she gave me Basha, who gave me Judy, who gave me Anna van Schurman, the first woman to earn a law degree, in 17th-century Holland. To keep from distracting the male students during class, Anna’s teachers forced her to sit behind a curtain. Now, at the Brooklyn Museum, I stood before her place setting and took in the deep orange folds of the plate, the simple white placemat edged in gold, its northern European austerity heightened by the rich velvet drapes celebrating the Italian Artemisia Gentileschi to her left. I thanked Anna and pondered my own curtain three decades before. Back then, as I despaired of ever seeing the other side, my Primordial Goddesses beckoned, sliding back just enough fabric to let me squeeze through.

Shares