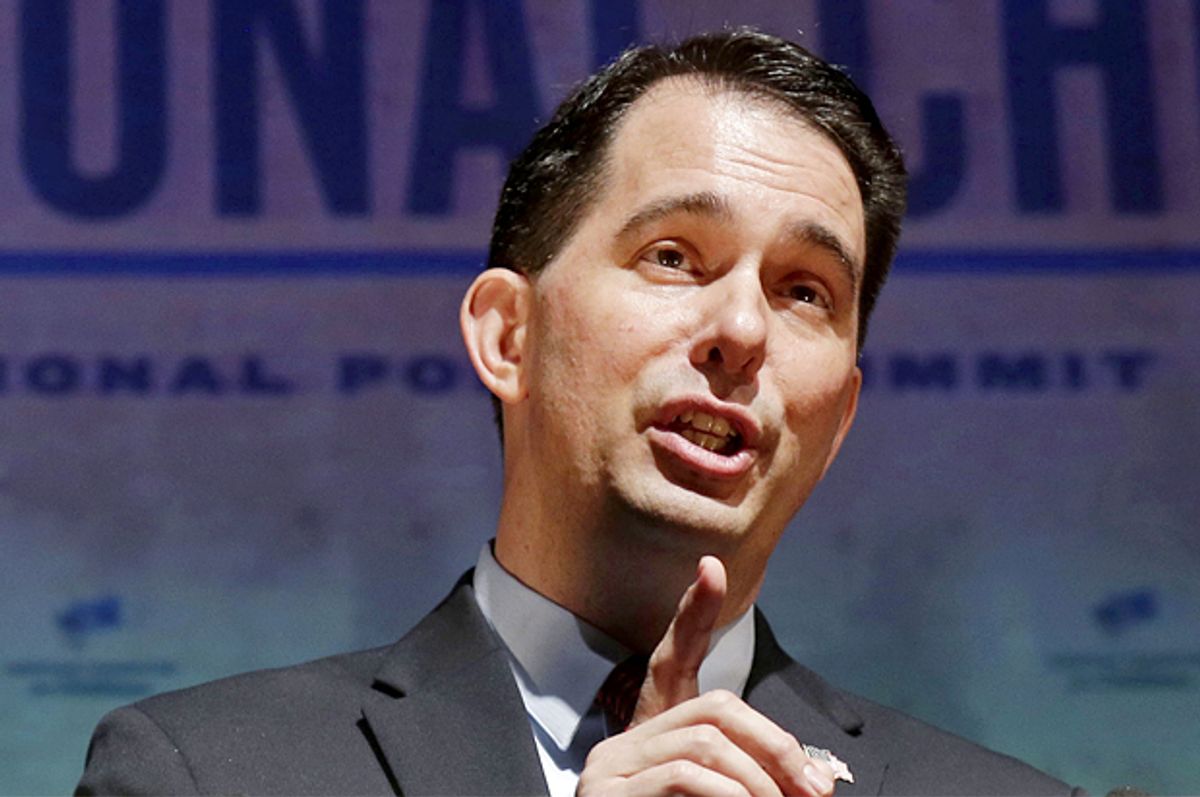

He’s effectively been on the campaign trail since at least January, but Wisconsin Gov. Scott Walker finally made it official on Monday and announced his entrance into the 2016 presidential race. Among the Republican field’s top-tier candidates, he is generally seen as the one most capable of uniting the party’s various extremists into one big coalition against Jeb Bush. It doesn’t matter if they’re religious fundamentalists, corporate CEOs, free-market ideologues or angry white populists; Walker knows how to talk to each one without alienating the others.

Most politicians try to be all things to all people. Yet throughout his career, Walker’s opted for a different tack. Rather than trying to be everything to everyone, Walker tries to be the ultimate conservative Republican, the kind of politician party activists adore and see as a fellow-traveler. But instead of embracing the far-right’s favorite policies at any given moment, Walker’s done this by engaging in vicious fights with the so-called liberal establishment. Walker seems to believe, in other words, that conservative Republicans will judge candidates by their enemies much more than their friends.

Viewed through this prism, Walker’s career isn’t the story of a public servant who tries to make life better for all of his constituents. Instead, his years in the Wisconsin State Assembly, in Milwaukee County, and in the governor’s mansion look like a series of increasingly desperate battles, waged by a conservative ideologue and against common symbols of liberalism. The foundation of his career is conflict — with “poverty pimps,” union “thuggery,” Planned Parenthood, fraudulent voters, liberal academics and, depending on the audience, undocumented immigrants. Name almost any archetypal liberal Democrat, and the chances that they’ve quarreled publicly with Walker are good.

This isn’t simply a natural consequence of Walker’s operating in Wisconsin, even though politics in the state is much nastier and more polarized than many appreciate. On the contrary, there’s abundant reason to believe that Walker governs this way because he wants to, not because of circumstance. When he spoke at a D.C. breakfast in late-November of 2013, for example, he argued that bipartisan, “divided government” is “not necessarily a good thing.” Sharing power with the other side creates “a lot of gridlock,” he said. The barely hidden subtext of Walker’s remark — which, to be fair, is probably right on the merits — is that compromise isn’t desirable. It’s better to simply win.

Toss those remarks aside, though, and the overall picture is still the same. The most consequential decision he’s made as governor, for instance, was the union-busting budget he passed early in his first term. One of the reasons the budget was so controversial — and caught so many Wisconsinites flat-footed — was because Walker never made union-busting a focus of his 2010 campaign, regardless of what he later claimed. That budget was an example of Walker seizing an opportunity to blow up the very structure of Wisconsin liberalism. It was Walker following Rahm Emanuel’s advice, not wasting the economic crisis that helped him get elected.

Walker’s doctrinaire conservatism and sharp elbows did not go unnoticed in Wisconsin. In fact, his complete lack of interest in perpetuating the myth of Midwestern niceness is one reason why his union-busting inspired such a massive backlash. But Walker’s managing to withstand that backlash, and win two more elections, is a big point in his favor among conservatives. If he had won reelection without polarizing politics in his state even further, his candidacy would lose some of its luster. These people believe GOP losses can always be blamed on moderation. Walker’s story seems to provide much-needed evidence.

It may ultimately be the case, however, that Walker’s bone-deep understanding of the conservative movement does him more harm than good. He’ll certainly be in the running for the kind of primary voters Sen. Ted Cruz is targeting, but there are plenty of Republicans who are close enough to reality to see that being insufficiently right-wing is not the GOP’s issue. They’re not especially interested in Walker’s eccentric devotion to Ronald Reagan; they’re interested in a general election candidate who they think can win. And the donors who hold the keys to the nomination are equally unsentimental. They simply want to maximize the return on their investment.

If Walker’s only real obstacle to winning the GOP primary was Bush, he might be able to prevail despite opposition from the elite. Every once in a while in American politics, genuine people-power can outmuscle concentrated wealth and win. If you’re the kind of conservative who thinks John McCain is a liberal, though, Walker is not your only option. When it comes to winning elections, his best days are probably over. But if he ever ends up in the administration of a Republican president, conservatives will at least know who to call when they’re hoping to hear from one of their own.

Shares