“Lights.” That’s what we say on the trading floor when our phone rings. And by phone, I mean dealerboard—a large electronic panel with communal and direct phone lines, a squawk box (the hoot), and a small TV screen. If I need to pick up a trader, syndicate, sales, or research line, or even broadcast myself to the entire trading floors of Hong Kong, Singapore, Tokyo, London, and New York, it’s all right in front of me. There are so many phones ringing at all times on a trading floor that we generally have the ringer volumes set at barely audible levels. For the uninitiated, it can be easy to miss a call unless you are paying attention. I have my dealerboard programmed so that the lines that I care about will flash in green and the lines that I don’t care about will flash in red, hence the term “lights.”

Chapter One of Trading Floor 101 for interns and analysts details how to answer the phones and operate the dealerboard. I have seen trainees reduced to actual tears for not answering the phone fast enough, accidentally dropping a line, or listening in on a call and forgetting to use the mute button. For a generation of kids who grew up without a home phone, basic telephone etiquette is increasingly an issue.

“Are you fucking retarded? How the fuck can I trust you to sell a bond if you can’t even figure out how to answer the fucking phones?” I’ve said it many times. I’ve heard it many times. It’s been said to me once.

The drawback of dealerboards at this time was they didn’t have caller ID, so it was impossible for me to screen my calls. “Hey, we’ve got a situation.” It’s Benny Lo, the head of the China coverage team, calling. “I’m hearing that XXXX is about to announce a deal away from us, mmm’kay? It’s likely Morgan Stanley as sole bookrunner on the deal.”

Missing a deal is not a very pleasant experience. You have to explain it to your boss and sometimes to his boss. And when you’re sitting in Hong Kong, you also have to explain it to the product (emerging markets credit) boss in New York. The only thing worse than missing a deal is missing a deal and having your boss see it hit the tape before you do. One of your clients is doing a deal and you don’t even fucking know about it. Fortunately, I am responsible for structuring, pricing, and selling the deals, so I don’t have to worry too much about being accountable for the direct relationship. By that I mean I still get yelled at, but at least I won’t get fired over it. That’s on the coverage banker’s head.

It’s hard to imagine a scenario much worse than this. Morgan Stanley, one of our main rivals, is about to announce a sole-bookrunner deal for the first-ever high-yield corporate bond to come out of China.

“We need to get in this fucking deal,” Benny whines. No shit, Einstein. He is one of the most annoying and notoriously pedantic bankers I’ve ever worked with, but in fairness, this is a bona fide fire drill. “I’m arranging a call with the chairman for this afternoon, and I’m going to need you to be on it. It seems that Morgan Stanley has been telling them they can get a deal done at 10% and is charging them two points in fees.” (That means if the company raises $300 million, they keep $294 million as proceeds and the bankers get $6 million in fees.) For most of us, you need only a few of these deals under your belt each year to guarantee a decent six- or seven-figure bonus, depending on your rank.

Our strategy is fairly simple: lie through our fucking teeth. So with the help of our translator, I hop on to a conference call with Benny and Chairman Zhu, one of the richest men in China. Despite growing up in the shadow of the Cultural Revolution, without electricity or running water, Zhu has put together a conglomerate that spans real estate, pharmaceuticals, and commodities. To call him eccentric would be an understatement; he famously likes to remind people that he didn’t own a pair of shoes until he was sixteen years old.

How I articulate myself is largely irrelevant because so much of whatever I say is lost in translation. So I go for melodic tones and short bursts that exude a sense of confidence and conviction. A few overpromises and outright lies also help. “Put us in this deal and, as the number one bond house in the world, we’ll get you a better deal at a better price and at a lower fee.” Despite having done zero credit analysis, I explain to him that we can get him a deal done at 9.5%, 50 basis points lower than what Morgan Stanley had told him. How is that possible? I tell him that we know more investors and have more leverage with them because we do more deals than any other bank. We also have a better read on the market because our trading desk is more aggressive and therefore sees more flow. It’s impossible to quantify any of these points, so it’s more of a confident assumption than an outright lie.

My only real concern is that everything I tell him will be further buoyed and exaggerated by our enthusiastic coverage bankers in translation. It’s literally a game of high-stakes Chinese Whispers.

I feign surprise that Morgan Stanley is planning on charging him 2% in fees. What an outrage. For the privilege of helping deliver the first-ever high-yield corporate bond out of China, we’d happily do the deal for 1.5%. Chinese people are particularly sensitive to the thought of someone trying to rip them off.

It’s also a good time to remind them that we are, and have been, active in lending to them. Part of providing low-margin services (loans) to clients implies that they reward us with higher-margin business. How do you say Glass-Steagall in Chinese?

Just like that, we’re in.

Now, the fun part. I get to call up my counterpart at Morgan Stanley. “Hey, Chico, you know that deal you think you’re announcing for XXXX next week?” (I use the term “Chico” as a generic and dismissive nickname [along with “Bubba” or “Fuckstick”] for people as a tribute to my former colleague in London.) Of course, he has to play coy; no banker would dream of discussing his nonpublic pipeline with a competitor. “Well, guess what? Now we’re joint books. Since we’re on the same team, we might as well get on the same page in terms of how we’re going to get this deal done.” That’s just another way of saying, “Bring me up to speed on your months of hard work.”

“Call you back.” Click. He hangs up, presumably to call his own China coverage bankers to find out what the hell is going on. Five minutes later, he calls back. “You motherfucker. You guys pitched this at 1.5% fees and told him he could get a single-digit coupon.” So now, they have gone from having a prestigious deal all to themselves, and looking at $6 million in fees, to having a fifty-fifty deal and only making $2.25 million. In terms of his bonus, and how we look at this situation, I’ve just taken a Patek Philippe off his wrist and put it on mine.

The next day is the kickoff meeting with the client to discuss market conditions, execution strategy, and deal logistics. If I can avoid these meetings, I do. It’s the responsibility of the coverage bankers and execution team. My job is to stare at screens and talk to traders, salespeople, and investors and get the deal done, not to glad-hand the issuers. I’ll typically call in to the meetings, say my part regarding markets and strategy, and then drop off; there’s no point wasting my time sitting through a discussion on documentation and other legal formalities.

Ten minutes before the big meeting starts, my dealerboard lights up. It’s Benny, panicking because he’s stuck at the airport and not going to make it back in time. “We clawed our way into this deal; if we’re not there, Morgan Stanley will try and get us kicked out. Since you spoke to the chairman, can you please go in my place, mmm’kay?”

Typically, it takes about fifteen minutes to leisurely walk from our offices to theirs, circuitously weaving through walkways that hover above the streets of Hong Kong, slowing down through the various connected office buildings along the way in order to enjoy a brief air-conditioned respite from the sticky, smoggy, heat. By comparison, a taxi would take about twenty minutes with the traffic.

I’m afforded no such luxury today; by the time I get there, I got a serious schvitz going on. I steam into Morgan Stanley’s office feeling like I’m walking into the funeral of the guy I murdered. At least the client is happy to see me; I’m the hero who saved him a bunch of money on fees and promised him a cheaper deal.

I look around for a place to sit at the conference room table. The way these meetings work in terms of etiquette is the client, the senior bankers, and the immediate deal team usually sit around the boardroom table, and then the analysts and other junior support staff sit in the chairs that line the walls of the room. If not, they stand.

At least Morgan Stanley is gracious enough to have saved me a seat. Actually they probably didn’t save it for me. It’s just one of those things that always happens, particularly within hierarchical cultures like Morgan Stanley; all the junior bankers are too terrified to take the last seat, for fear of someone more senior walking into the meeting. Having to relinquish a seat to a more senior colleague in the middle of a meeting is the banking version of the walk of shame.

However, I am now presented with one rather awkward dilemma. The only seat available is next to my ex-girlfriend, otherwise known as the Warden. Obviously I knew that she is still a banker at Morgan Stanley, but I had no idea that she would be on this deal team.

Unfazed and still thoroughly pleased with myself for getting into the deal, I grab that seat. In my mind, this is my movie scene moment and I am Ryan Gosling. In reality, I am more like Seth Rogen. I am drenched in sweat beyond the point of obvious discomfort. It’s a good thing Chinese clients don’t give a shit about personal hygiene.

Knowing that the stars will probably never align like this again—that we would be mandated with Morgan Stanley (it’s usually us or them), that I’d be doing a high-yield corporate deal (not our traditional strength), that my ex-girlfriend would be the banker staffed on the deal (she does more traditional leveraged finance), that I would actually attend the kickoff meeting (which I never do), and that the only available seat would be next to her (I hate being late to meetings)—I have to do something to make it memorable. I have to.

During the meeting, there isn’t much for me to do or say. On the assumption that they were going to be sole bookrunner, Morgan Stanley has the deal fully baked in terms of execution and roadshow strategy, and given the disparity of what we had each pitched the company on pricing, we avoid any kind of discussion on the topic. I throw out a few “I would agree with that” lines just to keep my voice fresh.

My ex-girlfriend, on the other hand, decides to use this opportunity to showcase her knowledge of the covenant package (the specific promises or stipulations listed in the indenture designed to protect lenders) and to demonstrate the depths of her relationship with the client, seemingly all for my benefit—as if I needed a reminder as to why things didn’t work out between us. Just as she is repetitiously rephrasing her boss’s words—Morgan Stanley bankers are famous for repeating each other, just using different phrases—I decide to take her down a notch and hopefully also expedite the meeting. Under the table, I remove my shoe and begin to gently caress her ankles. My disgusting, moist sock then glides up and down the back of her calf. Surprisingly, she’s able to fight through it like a champ—even pausing to give me a friendly smirk.

I’m not going to let this deter me. The next time she opens her mouth, I decide to take my equally clammy hand and slowly slide it up from her knee, stopping just at the point where her thigh meets the seam of her skirt. Then I just leave my hand there, teasing the edge of her skirt with my index finger. That was enough. She doesn’t speak for the rest of the meeting.

The deal hasn’t even started yet, and already, I know it’s going to be eventful. The roadshow includes stops in Hong Kong, Singapore, London, New York, Boston, and Los Angeles—in that order. The idea is that you whip up interest and momentum from anchor accounts in Asia, where the investor base is more familiar with the credit and the risk, such that by the time you are meeting European and US investors, you have the ability to convey a sense of momentum and strength. This also allows you to engage these typically larger and more influential investors in the context of the yield discussions (informal price guidance) derived from the early investor feedback out of Asia.

From the outset of the roadshow, it’s very clear, and unsurprising, that investors do not care about this deal at all below 10%. The genesis of my recommendation to the company wasn’t based off any roll-your-sleeves-up credit work or investor sounding; it was simply a function of saying, “Okay, what number do we need to show the client in order to get in on this deal.”

Our roadshow efforts are not helped by the fact that Chairman Zhu is not your typical CEO. In one investor meeting, he is asked about the quality of construction in one of his real estate developments. “Stupid question,” he says through a translator. “I don’t want you to invest in my deal.” Then he abruptly gets up and walks out of the meeting, leaving a potential $50 million anchor order behind.

In another meeting in New York, with one of the largest emerging market funds in the world, he lights a cigarette and just sits there puffing away. This is Mayor Bloomberg’s New York; you can’t even smoke in a bar. The investor, a hard-core amateur triathlete, declines to participate in the deal.

Given his propensity to chain-smoke, Zhu also has the not-terribly-subtle habit of clearing the phlegm from his throat whenever he feels like it. It doesn’t matter what’s happening or who’s talking.

European and US investors aren’t accustomed to meeting a Chinese client like this. Each day, at the first meeting after lunch, he’ll spend the entire hour aggressively picking at his teeth with a toothpick, which is clearly not at the advice of a dentist; he’s never seen one. If Winston Churchill said Brits have “honest teeth,” there’s no adequate description for what this guy has going on inside his mouth.

I don’t think he even cares about the meetings. His only stipulation, other than demanding that banks include young attractive females on their roadshow teams, is that they find the most authentic Chinese cuisine in each city because he refuses to eat Western food. He does make an exception in Boston, insisting that the entire roadshow team join him at Hooters. Imagine ten bankers in suits afraid to order beers, just because the chairman asked the translator to ask the Hooters manager to go find some Chinese tea.

This is the first-ever Chinese corporate high-yield deal so many investors have never seen anything like it. Of course, all the bankers are panicking, including Benny. I love it. I tell him to calm down: “Perfect, now we can blame the chairman when we have to tell the company that this deal is going to come in at least 50 basis points higher than what we promised.”

Benny is not convinced. “I don’t think you understand. This guy does not give a fuck. He’ll walk, mmm’kay?”

That’s what they all say, and then we have to go through this little song and dance where the client pretends to be unhappy with the outcome. But then they have no choice but to accept the terms as dictated by the market. The market is the market.

At the start of each day, the syndicate bankers lead the market update calls with the deal team, running through headlines, reviewing credit market conditions, and summarizing the day’s schedule of investor meetings. We do the same thing at the end of each day, but with greater emphasis on specific deal-related investor feedback. This is our chance to gradually work the client’s expectations back to reality with some negative feedback.

After several catastrophic days on the road, the relationship bankers delicately convince the chairman to come back to Hong Kong and allow the rest of the deal team—including his highly impressive, Western-educated CFO—to complete the remainder of the roadshow on the company’s behalf.

Not only have we been telling the deal team that market conditions have weakened and investor appetite for risk has diminished for first-time issuers, things really have deteriorated. We’re now looking at a market-clearing transaction in the context of 10.5%, or 100 basis points higher than what we promised—not an immaterial difference in the context of a $300 million deal.

The time has finally come for us to drop the hammer; we’re already late on providing formal price guidance to the market. We’ve been whispering “low/mid-10s” to investors, and even that doesn’t get them too excited. We now need the chairman’s approval to go out to the market with official price guidance in the range of 10.5% area. This is by far the most aggressive we can be. Attempting anything tighter substantially increases our chances of having a failed deal.

Benny is a fucking idiot. He jumps at the chance to host the next meeting with the chairman in our office without really understanding that we will now have to deliver the bad news in person. Our counterparts at Morgan Stanley are more than content to listen in on a conference line—undoubtedly laughing as I get crucified as the bearer of bad news.

We meet the chairman and his entourage upstairs on our client reception floor. It’s a fucking zoo. Once again, Benny has outdone himself. In a misguided attempt to demonstrate our support for the deal and for the client, he has teed up every senior banker imaginable to come out, shake hands, and say something about how committed we are personally to overseeing the success of this deal. It’s known as the Citi Swarm. Not only that, since this is a new client relationship to the firm, everyone has crawled out of the woodwork— private bankers, commercial bankers, transaction and cash management professionals, aka the guys who wear the brown suits.

After brief introductions, I lead the parade downstairs to give them a tour of our impressive (by Asian standards) trading floor.

“Chairman Zhu, this is our team of credit traders, the largest team in Asia. They will be responsible for making a market in your bonds and supporting the deal.” I pause for translation, while directing their gaze down a long row of bodies staring at screens, pounding away on keyboards, amid the energetic buzz of dealerboards lighting up. We get a polite acknowledgment from the desk head and then slowly move on to the next row. I don’t even think the chairman gives a shit; he’s already spotted the credit derivatives desk assistant. She’s a 5, which is more like a 7 on a trading floor, but he doesn’t appear to be quite so discerning when it comes to the talent.

“And this is the team of salespeople. They have been responsible for setting up the roadshow meetings for you and are working with their clients to generate the orders and interest in your deal.” As I am waiting for translation, I pull the head of hedge fund sales away from his desk and bring him over to the group. “This is the head of the team. His number one priority right now is selling your deal.” The chairman nods; they shake hands.

We finally work our way over to my boss’s office, where we’ll be holding the meeting. Again, it’s all very impressive. It’s a large glass office, prominently situated in the corner of the trading floor. The only problem is that there are so many people that we are literally overflowing out the door and onto the trading floor.

I wait uncomfortably for everyone to dial in: the underlings in Shanghai, the traveling roadshow team, and my dickhead counterpart at Morgan Stanley sitting contentedly at his desk a half mile away.

I dispense with the small talk and jump right into our issue: there is a successful deal to be had; it’s simply a function of price. I’m confident in my ability to convince him that what we’re proposing is a deal he needs to take.

Typically, I prefer conducting these price guidance discussions from the comfort of my desk, where I am just a voice on a conference call. I can read from prepared notes, instant message with my syndicate counterparts, and access any relevant or supporting market information. Instead, I am completely out of my comfort zone, huddled around a small conference table, staring at a very rich, very powerful Chinese Steve Buscemi. All I can hear is the sound of bankers fidgeting and the clamor of the trading floor pouring through the open door. I’m accustomed to tuning out distractions, but this is like taking the SATs while sitting under an overworked air-conditioning unit, next to a window overlooking a football field during cheerleader tryouts.

I take the team point by point through every facet of the transaction to date, pausing every two sentences for translation. Typically, it’s good to keep things succinct and simple for the sake of translation. But with so many senior bankers in the room, I have no choice but to articulate myself as if I’m talking to them as well, which is proving to be a bit of a challenge for the translator.

I talk about how comparable credit spreads have widened and market sentiment has weakened. I review each of the investor meetings they have had and some of the feedback that has come in, with particular emphasis on the price sensitivity of each investor, all of which is north of 10%. I remind everyone that initial price guidance is just the first step, a device to get investors enticed, to keep as many accounts as possible engaged and looking at the credit, and to generate momentum for a deal that will end up at a tighter level. “The best possible way for us to achieve a sub-10% final outcome is to start with an initial guidance that is substantially wider than that.” Of course, there is no way we’re ever getting below 10%, but I’m trying to work in baby steps here. “With that, it is our joint recommendation that we go out to the market with price guidance of 10.5% area.” I pause there for translation.

And then I just sit back and listen. My words are not met with a warm embrace. A typical happy conversation in Mandarin Chinese sounds like a bunch of loud angry people yelling at each other. By comparison, these guys sound pissed. A couple of the more astute bankers who had been standing in the doorway quietly slink away; they don’t want to be associated with this inevitable train wreck. There’s a solid five minutes of aggressive back-and-forth between the chairman and various people on the phone, with everyone seemingly calling each other “n***a” over and over. (Phonetically, “nigga” is a crutch word in Mandarin, similar to “like” or “um.”) The translator doesn’t even bother.

Finally, one of the coverage bankers speaks up on behalf of the company. “The chairman is obviously very unhappy with this recommendation. He understands the strategy of starting at a number that is inclusive across the range of interest, with the hope of creating some price tension to achieve a better result. However, he cannot accept 10.5%, particularly as he had been told 9.5% just one week ago. He would like to propose price guidance at 10%, with the expectation that the final result will be closer to our target.” Everything is a fucking negotiation with these guys. At this point, we’re screwed. The chairman can’t be seen as losing face in front of his team, and we simply have no room to budge.

Just as I am about to respond with a polite version of “no fucking way,” an unfamiliar noise starts pulsating from our trading floor, like a malfunctioning squawk box. It gets gradually louder and then a little bit clearer; it sounds like a drumbeat and a cymbal. It can no longer be ignored. We collectively pause and look out across our trading floor just as it erupts into a full applause. Then the music starts; it’s Outkast’s “The Way You Move,” which had only recently worked its way back into the zeitgeist after the Maury Povich “Not the Father” video went viral.

That’s when we see him. Our head of hedge fund sales, the person I had introduced to the chairman as being responsible for selling his deal, is bouncing around the sales row with an impromptu, but remarkably well-choreographed, dance routine.

If this isn’t strange enough, he also has KFC chicken skins stuck to his face. This becomes evident when, mid-routine, he starts eating one of the skins that is sliding down his cheek. I later find out it was the result of having lost a bet.

Suffice to say, we never got to lead the first-ever Chinese corporate high-yield bond. But then again, neither did Morgan Stanley.

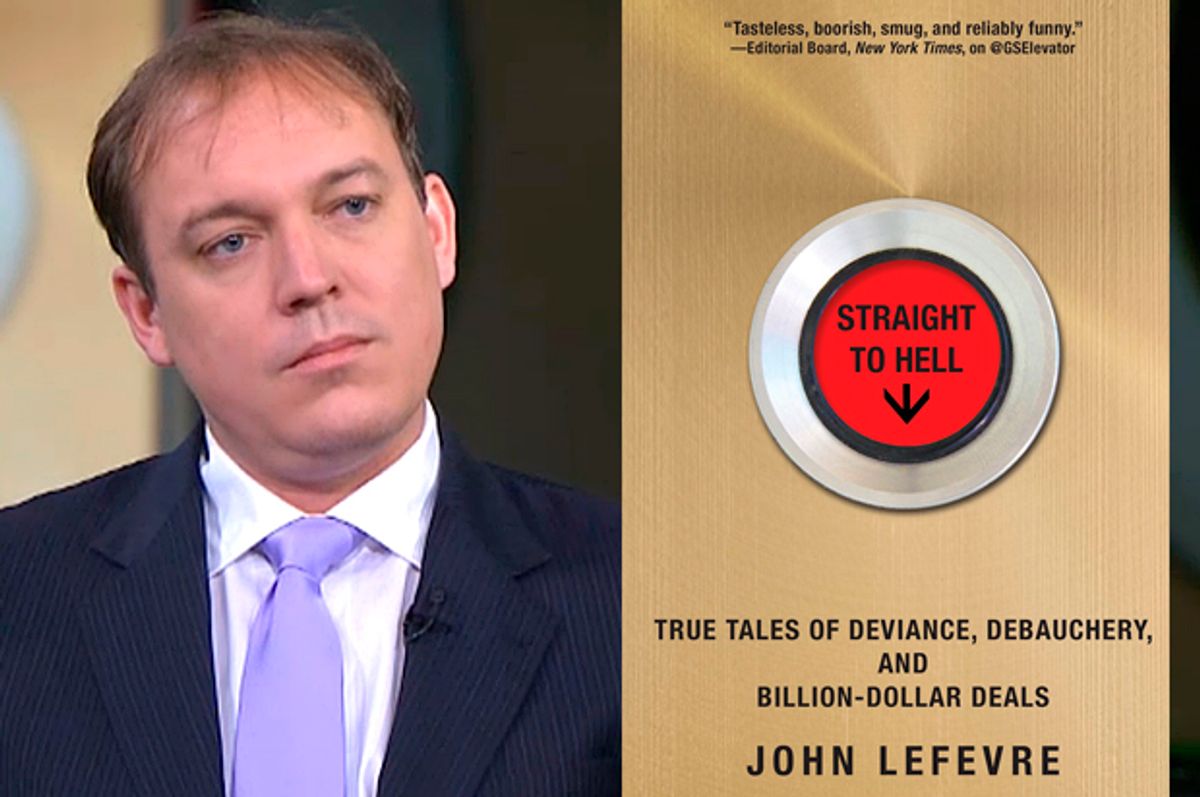

Excerpted from "Straight to Hell: True Tales of Deviance, Debauchery, and Billion-Dollar Deals" by John LeFevre. Published by Atlantic Monthly Press. Copyright 2015 by John LeFevre. Reprinted with permission of the publisher. All rights reserved.

Shares