They brought her into the courtroom with shackles on her ankles and handcuffs on her wrists. She was there, in court, for not showing up for a probation appointment. (She had been recently released from a 10-day drug detox center, but was on probation for traffic violations.) I sat a few rows back. She was turning her neck, searching for me. I walked up to her and tapped her on the shoulder and smiled. A courtroom guard walked over to me and said, aggressively, “Get away from her, she is still in custody.”

I returned to my seat.

She turned around again.

I blew her a kiss.

She mouthed silently, “I love you.”

That was the last day she was alive.

After the courthouse, I took her out for coffee and to buy some cigarettes. She was so happy to be out of jail. One week. The probation officer said one week in jail will “teach her a lesson.”

She called her mom as soon as we got in the car. She knew her mom was worried, and Sophie needed to hear her mother’s voice — the way a child needs to hear a mother’s voice when she is frightened. Sophie loved to talk — she told me all about the women she met in jail, how glad she was that she only had to be there for one week, because she had met women who were serving 18 months, two years, etc. One woman, she said, had asked her for some of her writing paper from the notebook she had. Sophie said the woman told her she had three children and had been unable to write to them since she was locked up. They sell paper at the jail. But you have to have money. Sophie gave her the entire notebook.

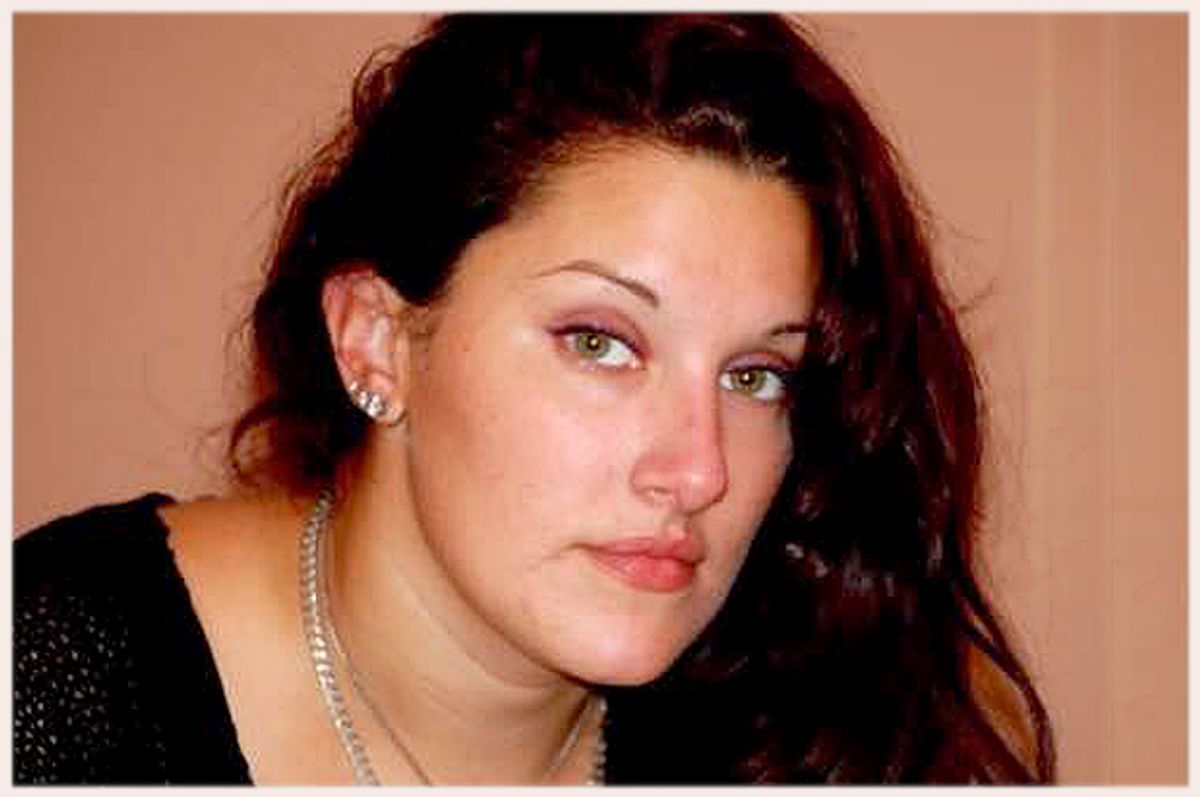

I was with my sister the day Sophie was born, along with my then 12-year-old son, Jake. It was always the four of us. And every year we went to Cape Cod and celebrated her birthday: Aug. 8, 1988. She loved to tell everyone that: 8-8-88. The summer she turned 10, in the cold waters off the Cape, she convinced me to join her in a small rubber boat. I agreed – Sophie took me out 10-15 feet from the shore and rocked the boat until she could flip me over into the water; the two of us were howling and laughing together. She sang at Jake’s wedding, “Red Is the Rose,” and when Jake became a father, she took care of his daughter, Emeline, the first six months of her life.

I knew Sophie smoked pot in high school. Other drugs? Maybe. None that she would readily admit to using. But after high school, and when we asked her specifically about using heroin when we took her to detox, she said that lots of kids were smoking joints laced with heroin. Smoking joints with heroin moved quickly to snorting heroin. She said it was common for young people at parties to have heroin readily available. She said buying heroin was easier than buying pot. She asked us why did she get addicted when she spent time around other people her age, friends, who tried heroin too, but didn't fall into addiction.

Sophie was a different child, though. She had an ear for music; she was a gifted musician. She sang in a coveted a cappella singing group in a performing arts high school. She performed publicly with the group, but was also terrified of singing in public. She played the bass, guitar, violin and piano. When she was 5 she could hear a song on the radio and sit at the piano and pick out notes, keys until she had the song. Her mother would stand outside the bathroom door and listen to her sing her heart out in the shower. And she could listen to someone speak and within minutes mimic them: voice, intonation, a comic’s gift to exaggerate an accent, a style.

And so her stories of one week in jail began. I heard them all—she had every voice, every story, including guards, apparently worn and bitter about their work—either that or inclined to believe that people who end up in jail don’t deserve to be treated like human beings.

We sat in the driveway of her mother’s apartment building, a two-bedroom they had been sharing for the last few months that Sophie was trying to get her life back on track. She told me about the bad choices she had made the last couple of years, about the guys she had dated. She had just ended a relationship with Sean, a troubled young man; she said they weren’t good for each other. But then she added, “But you know, Sean deserves to be loved, too.” I said, yes he does, but maybe not by you. She agreed. But that was Sophie—always a soft spot for the “throwaways,” the ”forgotten,” the “outsiders.” Perhaps she saw herself as an outsider, having spent 25 years of her life negotiating a relationship with an absent father.

We talked about what she would do with her day: see her dog, take him for a nice long walk, call her boss about painting the next day, get organized. I had to leave, get ready to go to my own job.

I asked her if she had any drugs upstairs; no, she said.

I reached over and hugged her and gave her a kiss, told her I loved her.

I said, “You know, I’ll never give up on you.”

She said, “You promise?

“Yes.”

I love you too, Ab.”

Our last words.

She got out of the car and walked up the staircase.

I saw her seven hours later on a bed in the hospital emergency room. She was dead. Her lifeless body on a gurney; an intubator down her throat. Her mother, my sister, curled up in a ball on the floor, rocking back and forth, crying no, no, no, no.

I asked the nurse to remove the tube from her mouth. She refused. Told me she couldn’t be touched until a coroner investigated.

My sister said, “Will you forgive me if I kill myself?”

I said yes, but please don’t do that.

My doctor, a week later, told me she must have felt immense shame from the jail experience.

I painfully agreed.

During incarceration, for a heroin addict, the body loses tolerance to the drug. A dose that once created their high, or relieved them of their pain, can now kill them. According to the National Institute For Health, incidences of fatal overdoses greatly increase after incarceration.

I wish I had known that.

I wished that the probation officer who wanted to teach her a lesson had said, don’t leave her alone those first few days, weeks. She will be wracked by shame.

I have asked myself a million questions about that day. I have a million regrets, a million explanations, but none will bring my Sophie back.

It’s difficult, too, to ask myself how this vibrant, beautiful young woman got addicted to heroin. Where do I begin to answer that question? And what would be the point?

I just want things to be different moving forward. In the book “In the Realm of the Hungry Ghosts,” an Australian addiction doctor says, “What we are doing hasn’t worked, it’s never going to work, and we need to change our whole approach. Tinkering around the edges isn’t going to make a difference.”

Our thoughts and judgments about heroin addicts are shaped by our limited experiences of understanding the pain and struggle of addiction, and the particular grief and pain of these human beings. No one wants to become a heroin addict. But we must let go of judging how someone attempts to relieve their pain, and find compassion and answers that will help them.

*This story has been corrected from an earlier version, which mistakenly stated that a drug addict develops a tolerance for heroin during incarceration. In fact, the addict loses tolerance, which is why relapses are so deadly.

Shares