Lately, there has been a resurgence in radio, specifically in the form known as the podcast, a digitized version of programming that can be downloaded at will. Thinkpieces have attempted to explain this trend, typically boiling it down to ever-shortening attention spans, too much time in cars, and the fact that Sarah Koenig’s "Serial" showed the business world that podcasts can be profitable. Arguably, its rise is also a symptom of creativity as a form of social activism. By creating their own podcasts and taking control of the content, people of color are hoping that their voices will be heard.

Yesterday, CollegeHumor alums Jake & Amir launched the Headgum podcast network, which curates and produces quirky programming designed to appeal to 20-something urban singletons. A quick glance at its racially diverse lineup affirms the truth of what the Mongrel Coalition against Gringpo states: “The Internet is not White. Get the Fuck used to it.” (Listen to them here.) But what does a nonwhite podcast sound like, anyways? Is the revolution in the voice, the content, or a whole lot of both? Can you tell by just listening if the speaker is Latino, Black, Asian, or a mixture of all three? On the radio, who cares who is speaking as long as they’re telling a good story? Well, we know that listeners patrol the sound of female voices, complaining about “vocal fry,” “up-speak” and basically covering their ears and saying LALALA when any woman who fails to sound like Jessica Rabbit breathes into the microphone. And when Chenjerai Kumanyika suggested we "Challenge the Whiteness of Public Radio," that launched a series of serious, NPR-led discussions about how think about what and who we — and those to whom we listen — sound like.

All speech is political, but sound is too. The lesson taught by British snob Henry Higgins was that language betrays class. In the U.S., which fixates on race as a proxy, it’s not just ethnicity or even subject matter that makes a culture “diverse,” but the overarching perspective. The invisible lens through which experiences are interpreted. According to this criteria, "Serial" wasn’t diverse despite being a story about the murder of Hae-Min Lee by Adnan Sayed, the son of Muslim immigrants, because its interpretive lens was both middle class and White. Some critics suggested it was maybe even kind of racist. But as Dave Schilling noted: “it's not so much that Serial is a terrible podcast, it’s that people who aren't white never seem to get the chance to make something like that.”

That lack of opportunities is precisely why some podcasts are now directly tackling the structural obstacles baked into the media itself. “As many have said,” Jennifer Baker noted in an email to me, “diversity is not a trend and when analyzing the reason for lack of representation in media, we have to look at those distributing and acquiring said media.” She hosts a necessary podcast, "Minorities in Publishing," created in order to provide practical information exposing the workings of the institutional machine.

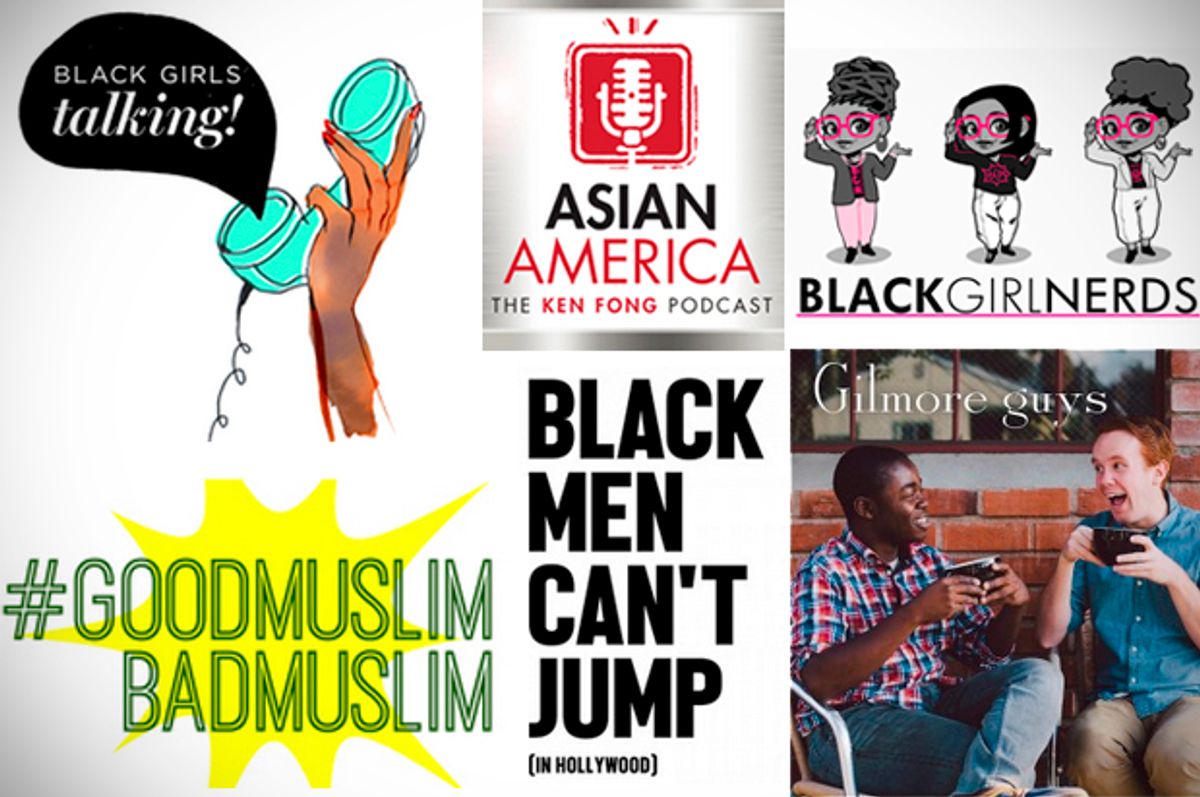

As podcasts continue to grow in popularity and number, the looming question is whether one run by people of color can or will become a cultural phenomenon like "Serial," or attain the nostalgic normativity of NPR’s "Prairie Home Companion," which is not only beloved by millions, but blissfully above average. The niche targeting of most independently-produced podcasts means that minority-led efforts run the risk of being FUBU – For Us, By Us, as the hosts of Headgum’s "Black Men Can’t Jump (in Hollywood)" comment with a combination of comedic outrage and dejection. "BMCJ" uses humor to critique the pitiful stereotyping of Black men in Hollywood films, even as hosts Jonathan Braylock, James III, and Jerah Milligan remain too aware that much of White America will refuse to acknowledge structural racism, let alone listen to their jokes trying to break it down.

Instead, for many creatives of color, the path to success begins by forging the tools required to make your own way in the world. The gendered counterpoint to "Black Men Can’t Jump" is "Black Girls Talking," an independent podcast hosted by Alesia, Fatima, Aurealia and Ramou (no last names are provided), four friends whose conversations sometimes segue into topics such as race and representation in Hollywood. This breakout podcast appears on a list assembled earlier this year by Mashable, which also pointed to the multi-media network, “This Week in Blackness.” Combining comedy podcasts with more biting fare, “This Week in Blackness” is home to the entertaining podcast "We Nerd Hard," featuring the site’s founder, Elon James White, in conversation with N’jaila Rhee, Fahnon Bennett and Aaron Rand, whose collective cynicism emerges from wit and weariness.

“This Week in Blackness” is also the home of "Black Girl Nerds," a podcast that pretty much shatters every stereotype about race, gender, and brainpower right there in its name. As "BGN" creator Jamie Broadnax pointed out: “this site welcomes girls of all races, but it was called Black Girl Nerds because it is a term that is so unique and extraordinary, that even Google couldn’t find a crawl for the phrase and its imprint in the world of cyberspace.” How awesome is "Black Girl Nerds?" Shonda Rimes follows it. Enough said.

These podcasts are all labors of love, but one of the reasons why "Black Girl Nerds" stands out is because it is smart, intersectional and organically inclusive. The strength of many podcasts is also their weakness, for their narrow targeting of a single group defined by race, age, political party, what have you, which runs the risk of Balkanization even as it creates a needed sense of community. For example, Ken Fong runs the podcast "Asian America," a series of conversations with prominent Asian-Americans. One of the people he interviewed was Phil Yu, who runs the popular blog, “Angry Asian Man,” as well as the linked podcast, "The Sound and the Fury."

These are podcasts run by Asian-Americans, interviewing Asian-Americans, about issues that concern Asian-Americans. Is it possible to be utterly specific and yet universal, too? Of course it is: For years, Garrison Keillor has mumbled on about Lutherans from Minnesota in winter, and his stories anchored a cult radio show holding stubbornly fast to a centuries-old variety format while broadcasting it out using the latest media technology, podcasting included.

The trick is to find an approach that not only hits a niche audience yet also transcends its material. Visually, beauty can accomplish this. Aurally, it’s comedy. It is a truism of the genre that the deeper the pain, the funnier the jokes. Zahra Noorbakhsh and Taz Ahmed, hosts of the podcast "Good Muslim, Bad Muslim," are blessed with razor-sharp wits and too much material. They are funny ladies, and increasing numbers of people are starting to listen to them—and to listen. To them.

Sound carries. The voice resonates. It timbre conveys conviction, hope, and dreams. Remember Ted Williams, the homeless veteran with the “golden voice”? Today, he’s running as an independent candidate for President of the United States, giving voice to the voiceless by advocating for the homeless. That is the power of a single voice, infused with such beauty that it stops people in their tracks. If he narrated it, a podcast called the Prairie Homeless Companion could even be a hit.

Shares