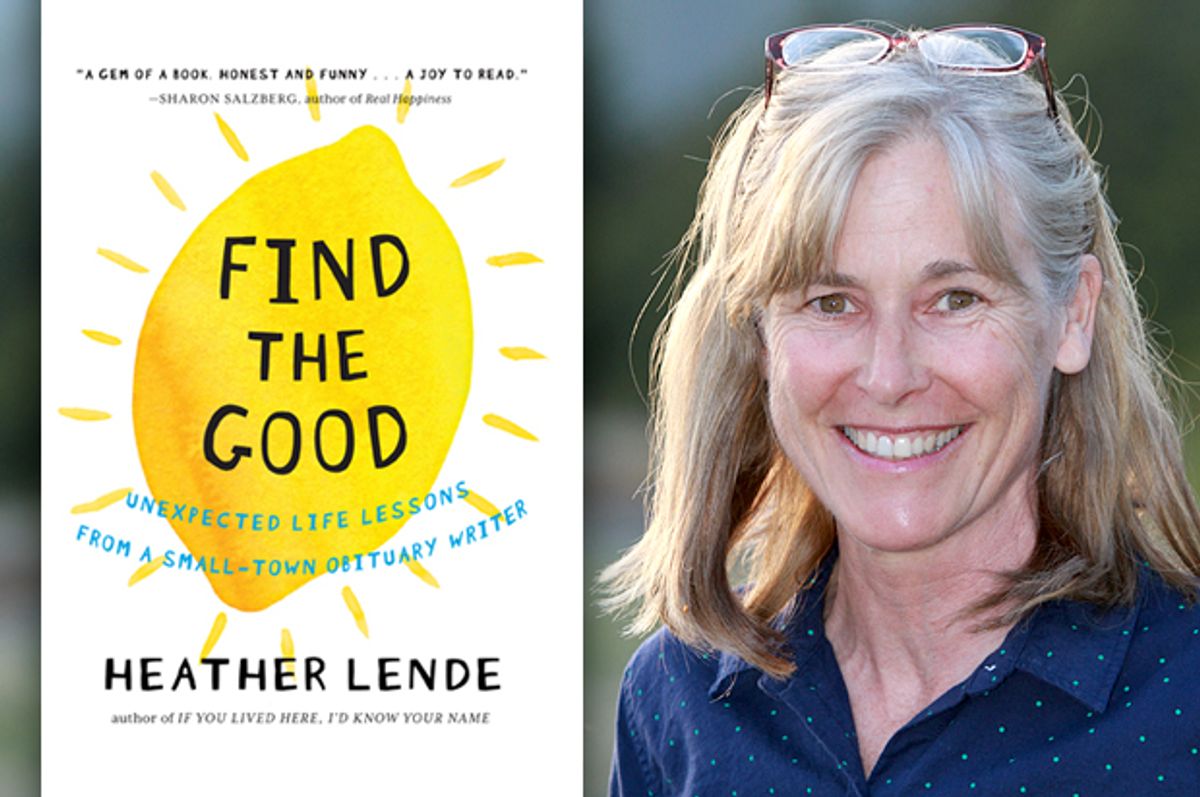

Heather Lende’s obituaries for her local newspaper in Haines, Alaska, started out as something she could offer besides a covered dish to her bereaved friends and neighbors. Her warm, intimate, clear-eyed send-offs have been read around the world, as have her books about life as an obits writer in a dangerously rugged place. I recommend all three: "If You Lived Here, I’d Know Your Name"; "Take Good Care of the Garden and Dogs"; and, the most recent from Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill, "Find the Good: Unexpected Life Lessons From a Small-Town Obituary Writer," which sounds sweet and mushy, but is actually wry and refreshingly candid. As it turns out, Lende writes engagingly about the living, too.

You write about older people in your town; you also write about young people, the native Tlingit, fishermen, hippies and loners. My favorite Haines resident might be Granny, who wears a large red helmet and shin guards and travels with a shopping cart and a dog. You were surprised to hear one day she had gone to London – as it turned out, to minister to the homeless during the Olympic festivities. Does Alaska attract eccentrics and originals? Do you “find the good” and the offbeat, as well?

I was at a wedding reception in the rain the other day, with lots of old friends and some new ones, and we actually talked about this, wondering if maybe we are a little nuts. We concluded that people who live here choose to, so they -- we—me — have that in common, and it shapes our community. Haines is not an easy place in many ways. Weather. Winter. Remote yet intimate. The people who like it here wouldn’t, or maybe couldn’t, live happily anywhere else, and so there is certain respect given to the other survivors. There are residents who brag, “I died and came to Haines.” I am one of them. Granny is more of a nomad. She calls herself a pilgrim, and she never came back to Haines from London. She is in Juneau now, to be closer to medical care and other services (there is no hospital in Haines), but her dog Sissy is still here, and attends church faithfully.

You were a New Yorker who went to Alaska on your honeymoon and stayed. Now you hunt and fish and built your own chicken coop. Were you outdoorsy and resourceful as a child?

I didn’t build the chicken coop, but I designed it, and I care for the hens in it and maintain it. I have always been athletic, and outdoorsy. As a child in rural New York, I was a tomboy; I played baseball, sailed and climbed trees.

Now, I like to hike, swim, ride my bike and hunt, but I am not a killer. I did go bear hunting, once, in the middle of the night with my husband and a friend. I can use a rifle, but I have never shot anything, and don’t want to. In Alaska, hunting is about eating locally, or it is for us, anyway. I like to eat good food, deer, moose—black bear-- and of course salmon, and I smoke my own fish and can it. But honestly, I’m not all that competent compared to many people in Haines. I have friends and family who are way better at filleting a salmon, or setting up a wall tent hunting camp, or running a skiff than I am. My garden is a tad wild and random, but we eat out of it all summer. I do the best I can, and I wing it.

You’ve seen a lot of death. You also had a brush with death when you were run over by a truck 10 years ago (the subject, in part, of your second book). Did either of these turn you to religion?

If I hadn’t had a faith practice before my accident, I certainly wouldn’t have found religion in being run over by a truck. But until then, I hadn’t realized how much I could rely on prayer or God, or hope, or whatever you call that “peace which passes all understanding” as we Episcopalians say. It was there when I needed it.

I don’t like it when well-meaning people say God never gives you more than you can handle. (That happens a lot when someone dies, especially tragically.) I am given more than I can handle all the time and I don’t think God has it in for me, and, compared to what so many in this world suffer, I am on easy street. What my faith did when I was hurt was help me accept the comfort of strangers in the hospital and nursing home, which was really hard, and when I write obituaries, I hope that same faith shows me how to be a comfort in whatever small way I can.

I was impressed to read that you filed a column for the Anchorage Daily News (now the Alaska Dispatch News) even while recovering from a crushed pelvis. How did you manage this? Literally.

I think it helped save me. I was immobilized, and indoors for months—two things that I didn’t think I could survive. The only thing I could still do was write. I had a friend bring a laptop to the nursing home, and he also emailed the column for me from his house, as there was no Internet at the home. Because of the injuries and the sedation it was hard to concentrate, so I had to write my columns differently. No more deadline panic. I carefully typed away a little every day, and edited and polished until I had something to turn in that was OK. Some were better than others. I’m grateful that the paper let me have the freedom to write about it all. I had hoped that the enforced discipline of writing this way would stay with me, but it didn’t.

You lead an active life now: you cycle and swim, coach the cross country team, serve on the library and hospice boards, sing in a choir, baby-sit grandchildren. You also once directed a musical when you were pregnant and had three children under the age of 6. Why? How?

I retired from coaching after 17 years, but remain involved in lots of community organizations. I directed "Carousel" years ago, mainly because no one else would. This winter I played Kate in "Dancing at Lughnasa," the same part Meryl Streep did in the movie, and loved it, especially the rehearsals. It was a great way to survive January and February, and cheaper than going to Mexico.

When you live in a small town, or are part of any community, you have to do your share. For me that might mean baking a cake for a library fundraiser, or sitting by the bedside of a dying elder, or hosting a weekly country music show (I play Merle Haggard, Nanci Griffith, Mary Chapin Carpenter, John Prine, Guy Clark, Lyle Lovett …). If I didn’t lead the kind of life I do, I wouldn’t have much to write about.

When I have a whole day to write, I don’t get much done. However, when I know I only have an hour or two, I am very productive.

I was in choir practice on a column deadline, and it had been hard week, I forget exactly why—but I bet there was an obituary, and the flu was going around, and there had been a contentious public meeting about something, maybe helicopters flying around the mountains with skiers-- when we started singing "Dona Nobis Pacem," “Grant Us Peace,” a favorite of ours. Then Nancy, the director, changed the arrangement and it was hard to hold the notes that long— we didn’t sound very good. She didn’t give up. Instead she had us practice staggered breathing, so we each helped the others sustain the notes in a seamless way. You don’t have to be a writer to see metaphors galore. Staggered breathing is such a great image on so many levels. That kind of moment makes me feel like I’m cheating when I go home and write it down, since it seemed to fall in my lap. I am handed stories like that all the time.

What do you miss because of your deadlines?

Dinner. Yoga … I am pretty good at waking up at 2 a.m. and getting it done. Although I missed an impromptu parade while writing these answers, but I didn’t really want to go anyway.

And is your husband annoyed when you get up at 2 a.m. to write? What is he like?

My husband is a steady Eddie. He doesn’t mind if I am all over the map emotionally, as long as I don’t wake him up. I know it sounds corny, but this life I lead is the one I embarked on with him, without a whole lot of thought when we were newlyweds—kids. I was 22, just graduated from Middlebury College, when we married and left for Alaska, and I’m 56 and a writer now, and he’s 58 and owns a lumberyard and hardware store in Haines, where we raised five children and now have five grandchildren.

The miracle is that as we both grew up and changed, we became the kind of people who we both still like and love. That’s been my great good luck.

Then, the strangest thing happened last year when he suffered nearly the same accident – a broken pelvis in a cycling crash—that I had had years before, and we repeated the process of patient and caregiver, just switching roles. That was so scary for me that I haven’t written about it—yet. He’s better now, but he has a limp—and doesn’t like it when I worry.

Usually I don’t write about issues too close to the bone in the moment they are happening, or that could put at risk relationships I care about. I take notes, and then I wait until they have been resolved. So to the reader a story may seem intimate, but to those involved and me, it’s old news.

My stories, the writing, the weird job at the paper writing obituaries for an old-fashioned editor at the Chilkat Valley News who still believes any local death is newsworthy, and would rather pay me $75 to write them than have the families do it themselves and pay him much more for the space -- everything I write is so rooted in my relationship with my husband, our family and this small Alaskan community that I can’t separate the “work” from my life. It’s all mixed up and connected, in a good way, and I guess you could say, it’s my inspiration.

You inspire me, but I can’t help squirming when I see your new book included in a “positivity bundle.” Please tell me you snarl and swear and watch trashy television.

Oh God! You have no idea. I am on the local planning and zoning commission and I come home from some meetings so mad. I’ve been arguing against making a new harbor and parking lot too big and ugly -- I care too deeply about it for my own good — and when I lost it (just a little) in a meeting, the chairman reminded me to “find the good.” Right then, I thought, "Oh no, what have I done?" Honestly, my writer self is my much better half. I don’t watch trashy television, but I tootle around on Facebook more than I should.

You have some things in common with another prominent Alaskan: a love of the outdoors, five children, a daughter who started a family without getting married. Do you hate being asked about Sarah Palin?

Yes. There are so many more accomplished Alaskan women. You have to thank her for the kooky, crowded Republican presidential field, though, since she proved that just running for national office is the fastest way to fortune and fame.

What do you read? Have you read the people to whom you’re often compared, like Anne Lamott and Annie Dillard?

I just read Kent Haruf’s "Souls at Night," and loved it. All of his books are in a way like elegies and in another way like country songs -- two of my favorite things.

I read the writers I’ve been compared to and think, really? Anne Lamott is so funny, smart and brave. "Traveling Mercies" is a book I go back to, as is "Bird by Bird." Annie Dillard is such a great wordsmith. Anna Quindlen is an inspiration, especially her old New York Times columns. I keep a collection of E.B. White’s letters and essays by my desk to learn from, and now read "Charlotte’s Web" to my granddaughters. Caroline, 5, is fascinated by Fern, and she has a little chair in the chicken coop where she sits to watch the chicks we got this spring.

John Straley, who lives in Sitka, is my best writer friend. He’s a poet, and was the Alaska laureate for a term. He writes funny and tragic novels like "Cold Storage Alaska" that are sort of crime fiction but different, since the characters are people I might know, and the setting is familiar, too -- southeast Alaska. But you don’t have to be from here to love them, any more than you need to travel to Texas to connect to Larry McMurtry.

Kay Powell, the retired obituary writer for the Atlanta Journal-Constitution, is a hero of mine. I also have a well-worn copy of "The Last Word," the New York Times collection of obituaries, at my desk — and your book on obituaries and the people who write them, "The Dead Beat," is a great companion of mine.

Thank you, Heather! I understand your desk is on a landing on the stairs of your house. How do you work in the midst of everything? Can you concentrate?

I like my exposed landing, maybe because it is in the thick of things. I can see the front and back entries to my house, the kitchen, the beach — it’s a good place to be. It’s not too comfortable. As for my concentration, I barely manage. I can move my schedule around more than when all the kids lived here, but sometimes I’m like a crazy person who can’t hear anything and is lost in my own head space. I don’t think my family resents my preoccupation at times like this, but when my now-grown daughters call, I might zone out and they will say, “Mom, what are you doing? Are you at your desk?” Now they pretty much all know that from 10 to 2 is my writing time, except of course when I’m on a deadline and then my perfect plans fly out the window.

But I have changed in the last 10 years, thanks to my accident and grandchildren, and time passing. Writing obituaries, and my own near miss, have helped me to pay much more attention to the people I love — and who love me back -- my children, friends, husband. My dog never misses her walks. The children all live nearby and I have two granddaughters next door. Silvia Rose will be 2 in September and she stands on the path between the houses and hollers “Mimi!” (my grandma name) like Marlon Brando yelled “Stella!” I love that.

I’m still a long way from living in the moment, as they say-- but I try. The thing about writing obituaries is that it reinforces the truth of what makes a good life — relationships -- and you can’t have them if you are holed up in an office yelling at everyone to be quiet and leave you alone so you can write about how important they all are to you —you know?

Marilyn Johnson’s most recent book is "Lives in Ruins: Archaeologists and the Seductive Lure of Human Rubble."

Shares