We hear any number of quotable nostrums about politics over the course of “Show Me a Hero,” the didactic, bracing and ultimately deeply moving HBO miniseries from David Simon and Paul Haggis about an obscure 1980s political crisis in an obscure place. One of the moments that stuck with me the most comes near the end of the show’s six-hour narrative arc, when a Yoda-like African-American consultant — played by the amazing Clarke Peters, well known to viewers of Simon’s “The Wire” and “Treme” — addresses a group of public housing residents, all of them black or Latino, who have been selected as the first residents in a new townhouse development in a largely hostile white neighborhood. (I will try to be responsible about spoilers, since only the first two episodes of “Show Me a Hero” have aired. Bear in mind, though, that the show uses the real names of real people, and concerns actual events more than 20 years in the past.)

When the incoming residents begin to complain about the unfamiliar rules and regulations of their new single-family homes – most of them have presumably never mowed a lawn – and about the perceived patronizing attitude of police and city officials, Peters’ character interrupts. Change is never easy and never predictable, he tells them. It can be good or bad, and quite likely both. The only thing you know is that it will be different. By signing up to leave the dilapidated and crime-ridden housing projects on the west side of Yonkers, New York, and move into newly built houses surrounded by neighbors who don’t want them there and fought bitterly to keep them out, these people have decided to change their lives. Now is the moment to decide if that’s really what they want.

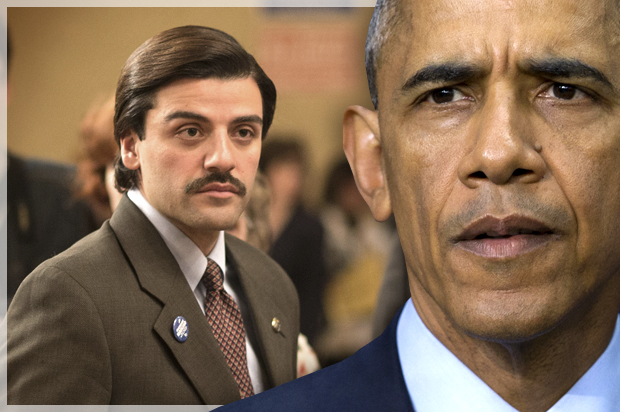

What this consultant is pointing out is that all the byzantine machinations behind the forced desegregation of Yonkers have almost accidentally given a few dozen poor people who’ve spent their whole lives on the wrong end of the system something anomalous: a taste of power, and some degree of moral freedom. But is that what they want? Is that what anyone wants? And what do we do with it when we get it? At a similar point in the story, Nick Wasicsko, the one-term mayor of Yonkers (played by Oscar Isaac) who serves as the deeply flawed tragic hero of the title – or at least appears to — laments that he didn’t do what he could or should have done when he held power, and vows to do great things with another grab for the brass ring. It doesn’t count as a spoiler to observe that Nick is deluded about nearly everything, including himself and the true nature of power and change, and that things don’t work out that way.

Deliberately labored for the first episode and a half, and directed throughout by Haggis in conspicuously unshowy fashion, “Show Me a Hero” is a deep delve into municipal politics that may seem overly granular and wonky even by David Simon’s previous standards. I’m not surprised that the first weekend’s ratings were not great: There are moments where the Op-Ed about government activism, or the civics lesson about the difference between top-down politics and grassroots organizing, threaten to overwhelm the storytelling. Simon’s post-“Wire” work has carried too heavy a burden of responsibility; you sometimes get the feeling he’s about to make a grimy 10-part procedural about the tragic saga of “Charlie on the MTA.” (Why doesn’t his damn wife just give him a nickel instead of that sandwich? There’s more there than meets the eye!)

But as I’ve already suggested, the real lessons about politics and power and the painful path toward racial justice in America to be found in “Show Me a Hero” are exceedingly complicated, and not at all obvious. This is a world where the dangerous possibilities of change are everywhere, but only if we have the courage and patience to look past emotional reactions and short-term political costs at elusive underlying realities. Political leaders like Wasicsko, or the Yonkers city council majority that threatened to drive the city into bankruptcy rather than accept a court-ordered desegregation plan, are far less in control of events than they imagine, or we imagine. Amid all their cynical and reactionary grandstanding, opportunities to display courage and leadership certainly arise – but we don’t always perceive them that way at the time, and the real heroism that drives social change is found elsewhere, among people never seen on the evening news.

If the desegregation crisis in Yonkers is little known today – and would be virtually forgotten if not for the book by longtime New York Times reporter Lisa Belkin, adapted here by Simon and co-writer William F. Zorzi – it made headlines from coast to coast at the time, as a national symbol of white working-class resistance to integration. And it’s abundantly clear that Simon doesn’t think this story is really about Yonkers, then as now an isolated and divided city of 200,000 people on the Hudson River that serves as a de facto buffer zone between New York City and the posh suburbs of Westchester County. To put it another way, if you want to model the contradictory weirdness of American politics in miniature, you could do a lot worse than Yonkers in 1987.

I’m going to assume that this is historical accident (or, more precisely, the repetition of a historical pattern) rather than authorial intention, but it strikes me that Nick Wasicsko, who made news as “the youngest mayor in America” when he was elected at age 28, has a lot in common with Barack Obama. An ambitious ex-cop turned lawyer with minimal political experience, Wasicsko ran for mayor as an outside force of change and unseated longtime Republican incumbent Angelo Martinelli (played here, and wonderfully, by James Belushi), who had gotten bogged down in scandal and crisis and lost the public trust. But after coming into office as a populist firebrand, Wasicsko quickly realized that Martinelli had handled the crisis in the only remotely responsible fashion, and found his own mayoral agenda sabotaged by an intractable opposition that refused to negotiate and was driven by not-so-hidden racism.

Of course the parallels break down at a certain point, but the differences are instructive too. Wasicsko ran what we might today call a “dog-whistle” campaign, never mentioning race but assuring Yonkers voters – who were then mostly white, working-class Catholics, many of them recent emigrants from decaying neighborhoods a few miles south in the Bronx — that he would continue appealing the court-ordered housing plan Martinelli had decided to accept. As mayor, he had to face reality, which included the fact that a federal judge named Leonard Sand (Bob Balaban in the series) was almost literally holding a gun to the city’s head, imposing escalating fines that would quickly deplete the treasury and shut down essential services unless the recalcitrant council could agree on a housing plan. Wasicsko did the right thing by forcing through a deal in the face of angry mobs and violent threats, but it was also literally the only thing he could do – which I’m pretty sure is exactly how Obama feels about bailing out the banks, handing management of the economy back to the same people who had wrecked it, and pursuing the Bush-Cheney “war on terror” on slightly modified terms.

As played by Oscar Isaac in perhaps the most textured and careful performance of his impressive young career, Nick Wasicsko had no idea that he was sabotaging his political career by tying his name permanently to an unpopular cause. (Obama, on the other hand, appears deeply grateful to be leaving politics behind, at an age when many presidential contenders are just warming up.) Whether or not Wasicsko came to believe that building public housing in east Yonkers was the right thing to do on its own terms, or to understand his city’s 40-year policy of deliberate racial segregation as a grievous moral wrong, is pretty much irrelevant. At any rate, it made no difference in terms of outcome. By all accounts, Ulysses S. Grant was given to using ugly racial epithets in private; he was also the only president between Lincoln and Dwight Eisenhower who used federal power to uphold the civil rights of African-Americans in the Deep South and combat the white-supremacist terrorism of the Ku Klux Klan. It might make a nicer story if Grant had been a more enlightened person, but which of those things is more important?

Simon and Zizzo’s script deliberately underplays the amount of overt racism in the Yonkers housing battle, which was all too clear at the time. That feels like a gesture forward to our own age, when even the most virulent Tea Party reactionaries have trained themselves to avoid certain words and phrases, and Republican candidates routinely quote Martin Luther King Jr. without bursting into flames from the sheer force of hypocrisy. In “Show Me a Hero” this strategy also has a dramatic payoff: When the N-word is finally spoken aloud, or spray-painted on a wall, it carries a violent impact that could easily have been lost.

In evoking the strange political universe of the Reagan years “Show Me a Hero” also evokes the end stage of the Cold War, which is not as irrelevant as it sounds. From the late 1940s through the early 1990s, under a range of Republican and Democratic regimes, the American political establishment felt an obligation to redress obvious social wrongs (or at least pretend to), through direct government action if necessary. Facing a global ideological enemy that purported to be an egalitarian society – and in some ways was one, far more than ours – had many consequences for America, and not all of them were bad. Today we are so thoroughly surrounded by the ideology of capitalism and neoliberalism (which is understood more as atmosphere than as ideology) that such solutions are almost never mentioned, and invariably described as impractical or counterproductive.

By dragging us back to the forgotten trauma of Yonkers Simon dares to suggest that federal housing policy, a thoroughly anathematized topic in mainstream politics, can play a role in addressing economic inequality and racial injustice. It’s no panacea, because there is no panacea for those enormous rifts in our society, and the progress made in Yonkers was incremental, small in scale and unsatisfactory. That’s not the same thing as saying that it wasn’t worth doing, or that we are forever compelled to let the “free market” decide who can live where. With the emergence of national figures who are actually willing to discuss these issues, including Sen. Bernie Sanders and New York Mayor Bill de Blasio, an ideological reformation may be underway. If “socialism” is no longer a dirty word, can “public housing” be far behind?

The title of Lisa Belkin’s book and Simon’s series comes from F. Scott Fitzgerald: “Show me a hero, and I’ll write you a tragedy.” But the true subtlety and power of “Show Me a Hero” comes from inverting those expectations. The real heroes of this story are not the guys who got elected on promises they couldn’t keep. They are the public housing residents who embraced change in the face of uncertainty and danger, or East Yonkers residents like Mary Dornan (played here in a quiet but shattering performance by Catherine Keener), who began as a fierce opponent of the housing plan and ended up, after meeting some of her incoming neighbors and learning about their lives, as the head of the welcoming committee.

I wouldn’t argue that electing mayors and governors and presidents is entirely unimportant, and I’m sure David Simon wouldn’t say that either. But when we become mesmerized by the endless revolving circus of electoral politics – which is depicted with increasing ruthlessness in “Show Me a Hero” progresses — and convince ourselves that political change is about voting for the right charismatic individuals instead of the wrong ones, we literally disempower ourselves and forget how social and cultural progress actually happen. If Nick Wasicsko was a tragic hero, his fatal flaw was a widely shared confusion: He believed that because he got elected he was actually in control.