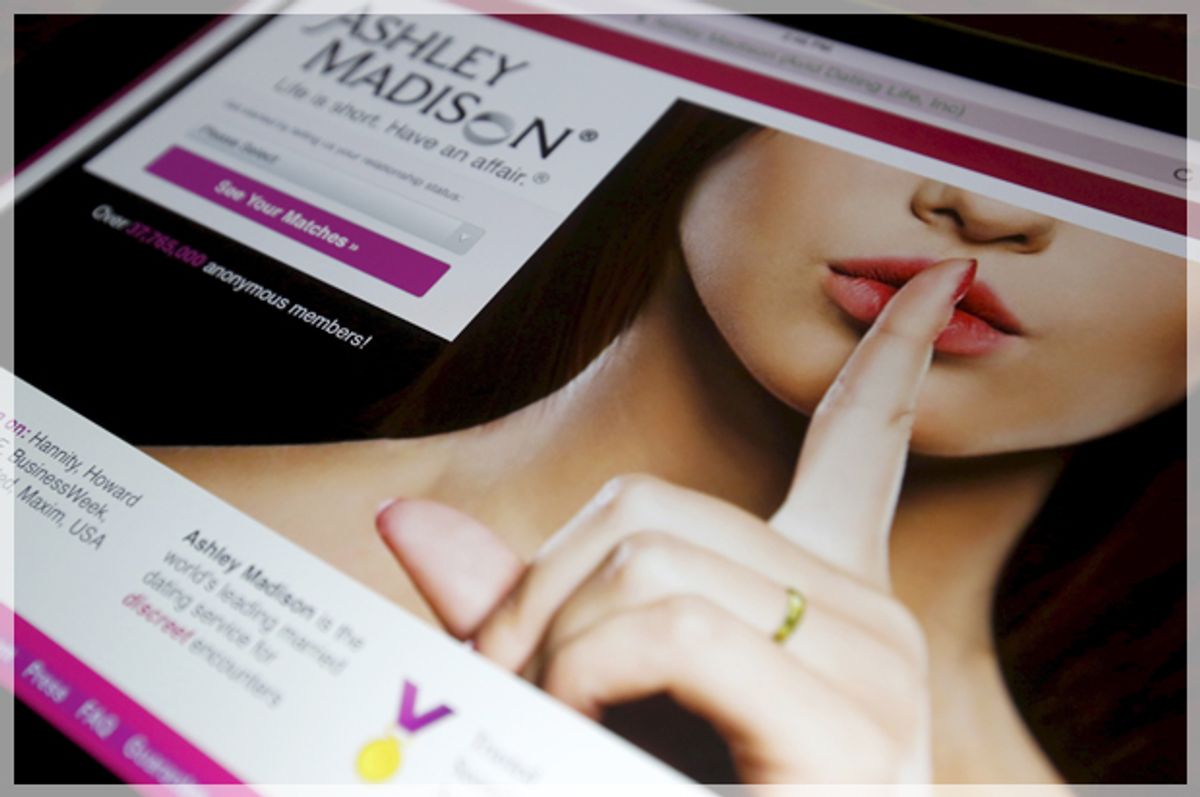

The hacking and ensuing data dump of Ashley Madison, a site that facilitates infidelity, is a moral and ethical minefield. It’s hard to see the story as having any heroes or even sympathetic sides. And who deserves more scorn – the adulterers, the website built on betraying marriages, or the group that has chosen to publicly expose its millions of members?

So far the case has provoked a huge range of responses – no real consensus has taken shape on it.

We spoke to Kate Manne, a moral philosopher at Cornell University, about marriage, privacy, feeling pleasure in the pain of others, and why two wrongs don’t make a right.

For a layman, this is a morally messy, morally complicated case. Millions of people – many of them admitted adulterers -- have had their private information spilled into the world… Is it any clearer to someone like you who studies this for a living?

I think it’s really natural to react to these sorts of situations by feeling either schadenfreude or sympathy for the cheated-on spouses – to not sympathize with the targets of the hacking.

One of the challenges here, which I think philosophically is hard to get past, is that we don’t have terribly sympathetic victims of this crime. But that doesn’t change the fact that this still seemed like a massive privacy violation that isn’t justified by the level of wrongdoing. And some of the users were probably not doing anything wrong at all.

So those secondary considerations that emerge after reflecting a bit more on it are a way of getting past the more hot, instant ways of thinking.

Does it make things different, from a moral perspective, that for some people marriage has been opened up and redefined over the last few decades? Some marriages are more flexible than they were in the’50s, say. At least, the rules seem to be changing.

That’s a good point. Even if you disagree with me and think these people were lying and cheating in the most scurrilous way and deserved the be hacked, that leaves the people who were in open marriages, who were playing around with poly lifestyles – which is increasingly coming to light as ways people live…

You also have people who are gay and closeted; it’s not to say that it’s right for them to cheap on their spouses, but it’s more understandable if you’re living under conditions where you’re not able to explore your sexuality. People who got married very young, or where there’s a huge taboo against divorce... There’s a huge difference between people clearly doing the wrong thing and those who were not doing anything wrong at all and you can now search for their names and have them pop up.

So the way you reckon it, the right to privacy is the more important issue here – privacy outweighs the moral breach of adultery. Is that fair to say?

I might put it a little differently. Imagine if someone was both a hacker and they were on this site – there’d be this question, as a thought experiment, which is worse? I think the cheating might be worse, depending on the back story.

But there are a lot of situations where people appear to have done, or have done, something really terrible. But the issue is, whose place is it to shame them and come up with what a proportionate punishment would be? That’s usually not a deliberate attempt to shame – it’s something else, and meted out by people in a more specialized position, who have a social role.

Right -- a judge, a policeman, a teacher, something like that. While this is an anonymous public shaming. It seems really medieval, doesn’t it?

Yeah – it has a lot of that flavor. I was thinking about Gamergate and Zoe Quinn… It’s good to be humble about what is wrong. The people shaming Zoe Quinn thought she had done the wrong thing; they thought she had cheated on her boyfriend, but it ended up being a lot more complicated… But people sympathized with him, they thought she was a cheater, and they jumped on her.

It’s easy to be overconfident that you’re on the side of right in these situations. There’s a point about epistemic humility: You should be a little bit cautious about thinking you’re on a moral crusade and bringing people to justice. It can be true, but it’s the kind of thought you want to question and back off from.

There’s a vigilante quality to this, isn’t there?

Definitely. We’re seeing a ton of that these days. Social media has allowed this. Sometimes you end up getting a crowd-sourced response to something bad that ends up being excessive and not allowing the person to seek forgiveness, or rethink things, or have hope to restore a relationship after they’ve done something wrong. Hopefully in most contexts there’s an ability to repair a relationship… But not if it’s on Twitter.

Marriages do recover from affairs, but when it becomes public, worldwide knowledge it becomes a lot trickier for a couple to reconcile, doesn’t it?

It does – because it’s humiliating for the cheated-on spouse, too. It varies couple to couple, but a big part of getting over an affair is getting over the feeling that someone has cheated on you – what does it say about you that they felt the need to step outside of a closed relationship? And now that it’s out there, it changes the interpersonal repair that would be possible if someone just came clean.

Does the amount of schadenfreude surprise you, and does it seem unfair?

Actually the amount of schadenfreude rarely surprises me – maybe I’m too cynical. It’s much more common than we’d like to acknowledge. People can be very moralistic.

If you think of morality as a kind of hierarchy, with people who are really good at the top to people who are really bad at the bottom, this allows you to raise yourself up in comparison to other people. Because hey, you may be mean-spirited, or have lied to your spouse – but you didn’t cheat on them. So you’re doing okay. It’s a bad way to think about your own moral status. You should elevate it – think about what you should do, about what’s right.

Elevating it at the expense of other people is not a great way to operate, is it?

It’s really antithetical to doing the right thing for the sake of doing the right thing. It ends up being moral narcissism.

Shares