The 2016 presidential election will be the second since the court’s disastrous Citizens United decision and the first without the full protections of the Voting Rights Act in place. That means big donors will have more sway over elected officials to dictate the agenda.

Already the wealthy are pouring money into the election: Politico reports that the 67 biggest donors, who have each given a million dollars or more have donated three times more than 508,000 small donors combined. A new report from Every Voice Center finds that individuals living in 1 percent of the nation’s zip codes (equal to 4 percent of the population) are responsible for half of the $74 million the 10 candidates who have raised the most so far. Every Voice reports that just three rich, and heavily white neighborhoods gave more to politicians than 1,248 majority African-American districts. But what do donors want?

Spencer Piston, Assistant Professor of Political Science at the Campbell Public Affairs Institute at Syracuse University, examined 2014 Cooperative Congressional Election Studies (CCES) data for Salon, and finds that “donors are more likely than non-donors to oppose the downward redistribution of wealth.” He finds that the mean income for donors is $74,999, but for non-donors in the sample, the mean income is $54,999. He finds that while 20 percent of non-donors in the sample consider themselves poor, only 7 percent of donors do.

There were gaps on class issues as well: with non-donors more likely to say the poor pay too much in taxes, and donors more likely to say the rich pay more than they should. While 46 percent of donors strongly agree that lawsuits are interfering with free enterprise, only 28 percent of non-donors strongly agree. Finally, 46 percent of donors say their first priority with respect to the budget is to cut domestic spending, compared with 36 percent of non-donors.

Obviously, these data are examining the smaller donor pool; the policy preferences and views of the wealthiest mega-donors are incredibly hard to discover. But they offer a key benefit over much of the other research on the effect of campaign contributions. Data that examine campaign contributions tend to focus solely on a broad left-right axis that combines economic and social issues. This makes it far more difficult to discern the influence of the wealthy specifically on class related issues. Research suggests that the richest Americans are rather liberal on social issues, but far more conservative on economic issues, but this nuance is lost on a one dimensional scale.

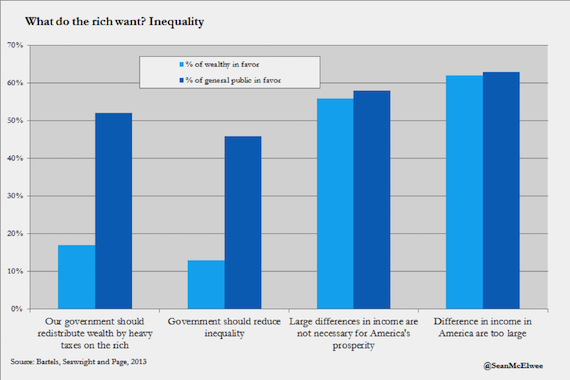

What about the race bias of the donor pool? Previously, I’ve discussed the work of Page, Bartels and Seawright, showing that the wealthiest Americans are far more likely to oppose government action to remedy inequality than the least wealthy (see chart). Their sample is nearly all (96 percent) white, and comprises 68 percent donors, suggesting that the views Piston finds at the lower levels of the donor rung are true at the highest levels as well, if not even more pronounced.

The rise of big donor plutocracy is especially disturbing given the rising evidence that African-Americans and Latinos have little influence over policy. A recent working paper suggests that African-Americans, and in particularly Black women, enjoy far less policy representation than whites. They even find that the Black/white representation gap might be bigger than the class gap. Another recent paper by Nicholas Stephanopoulos that used Martin Gilens’s massive database of public policy and opinions as well as state level exit polling found that women, people of color and low-income people have their preferences ignored by politicians. While it’s difficult to know what exactly is driving the differences, the authors of the above mentioned working paper suggest that partisanship, voter turnout and the strength of the views cannot fully explain the Black/white representation gap. In addition, more and more research on

It’s clear that to truly be a democracy, the United States needs to reckon with money in politics. We need policies to create an inclusive democracy. That means requiring full disclosure of all political spending, curbing the influence of lobbyists and eventually overturning the disastrous Supreme Court precedents regarding campaign finance. But simply reducing the influence of the wealthy isn’t enough. We need to empower ordinary citizens. That means fostering small donor democracy through public financing, which a 2012 study suggests could increase the diversity of the donor pool. A recent Demos report finds that at the lower levels, the donor pool is more diverse than at higher levels. Finally, we need to reduce turnout inequality, which further exacerbates class biases in political contributions. Automatic voter registration and non-partisan get out the vote operations and a re-invigorated Voting Rights Act can all work to ensure inclusive democracy.