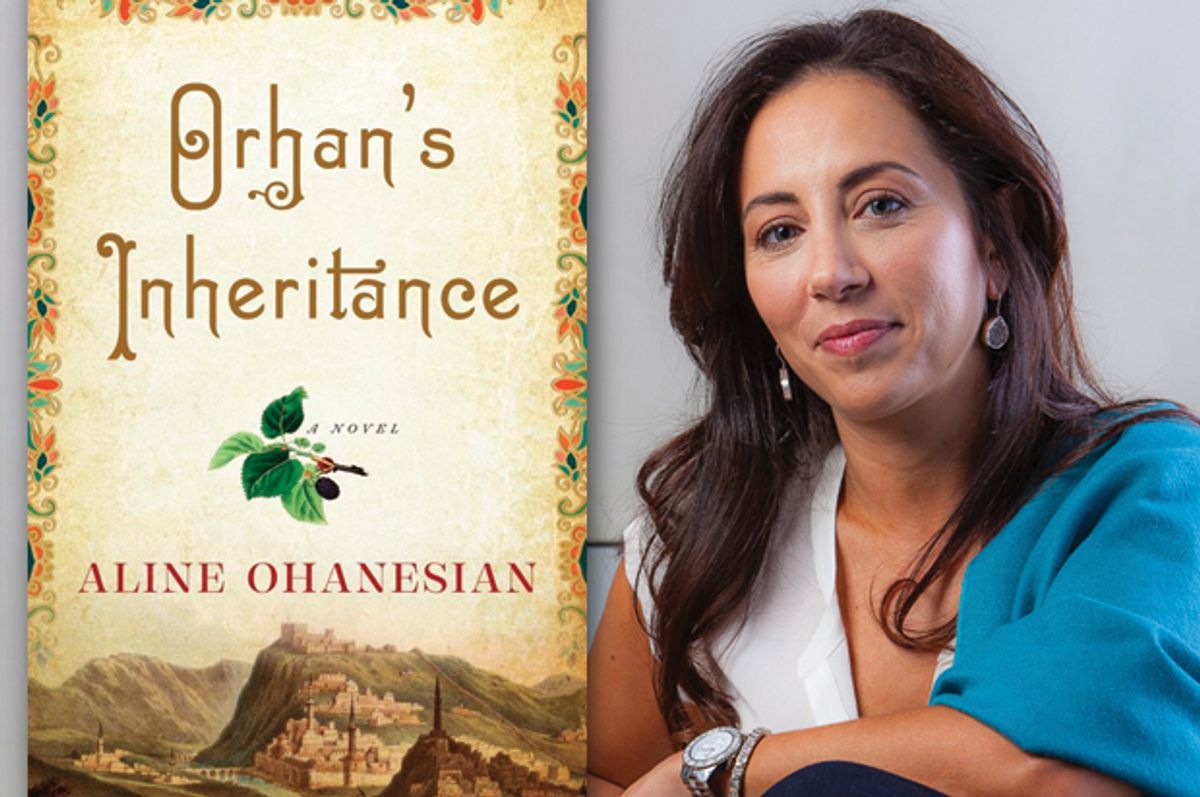

Some writers are called to fiction despite whatever more practical paths they had taken before the obsession with words and story took over their lives. Aline Ohanesian is one of these. In the midst of getting her Ph.d. in history (embarked upon so that she could keep reading while still being a good immigrant daughter) the voice of Seda, one of the characters in her debut novel, "Orhan's Inheritance," started coming to Ohanesian. Instead of dismissing this voice, as more normal, non-writerly folks would have done, she wrote down those first sentences. She tucked them into her diaper bag and wondered whose voice had come to her and what to do with it. What she ultimately did was keep on connecting with that voice, make up the parts she didn't know, do a ton of research into the period and fill in the blanks from stories she had heard from her grandmother. The result was "Orhan's Inheritance," a beautiful book about one of the grimmest chapters in history, the Armenian genocide, which has just passed the century mark. I read Ohanesian's book marveling at how deftly she had captured terror but also love and ultimately hope. Then I had the chance to talk to her and here is our conversation.

In my experience survivors do not like to talk about the trauma of the home country and thus most immigrants never tell their children or grandchildren the details of what happened. Was this your experience with your family or was there a family member who told you the stories? Alternately how much of the novel depended primarily on research? How did you mold these two, the told stories and the research?

I think what you say is true immediately following the trauma. Many in that first generation wanted to move on, to assimilate and to forget, but the past is a difficult thing to suppress. I’m convinced they were suffering from some kind of PTSD. Both my paternal grandparents were survivors, but it was my maternal great-grandmother who told me her story when I was only 8. I wove bits and pieces of her story into this novel.

I spent seven years writing it. I did way more research than was necessary, mostly because I love reading primary sources, things like diaries, letters and ledgers. I read dozens of history books and I spent some time in Turkey, visiting villages where they were still burning cow dung for fuel. I also immersed myself in literature that dealt in some way with that part of the world, everything from novels to poetry and children’s fairy tales. You can tell a lot about a culture from the stories told to children. I loved this process as much, if not more, than the actual writing, but there is a point when you have to put that all aside and delve deep into your characters

You did such a masterful job of moving through time, shifting seamlessly between past events and present tellings. How difficult was this to do? Is it a device that came to you easily or one that you struggled with?

The structure was made necessary by one of the underlying themes of the book. I wanted very much to make the argument that the past bleeds into the present, staining everything it touches. To do that, I had to look at how the events in 1915 affected the present. The structure answers the question, why is this story important? Why tell it now, 100 years after the fact?

Kemal and Seda’s long ago love story adds a sweetness to the horror of this particular chapter in history. Did you want to add a love story for this reason? Is there a way that love transcends the barbarity of the time?

I read somewhere that in any given situation human beings can either come from fear or love. It seems overly simplistic but I find it to be true. There was so much that was fear-based in this novel. The Turkish government’s decision to annihilate the Armenian population, Orhan’s decision to abandon his art, Seda’s unwillingness to talk about her past. All of it was fear-based. I felt I needed to balance that with the very real phenomenon, of people choosing love, be it familial or romantic, in the face of all that fear.

It’s the 100th year of the Armenian genocide. What does it mean to you to have your book out now? I believe that the writer is the voice of the people and telling the stories that cannot be told. This is both a lauded and cutting role. What is powerful to you about this role? What is most painful?

Writing this novel was my way of dealing with trans-generational trauma and a way to communicate that trauma to readers and to my two sons. It still shocks me when I meet well-educated people who have never heard of this episode in history. When I began the novel, I didn’t plan for it to coincide with the centennial. The timing had more to do with fate or kismet. All novels are deeply personal, and this one was especially painful to write. I don’t know if I’ll ever write a novel quite this personal again. That remains to be seen, I guess.

Seda says, “Everything we do is political.” Do you believe all writing is political? Is yours a political book?

Yes. Absolutely. I think we, the storytellers of society, have a great responsibility. Joan Didion once said, “Setting words on paper is a tactic of a secret bully, an invasion, an imposition of the writer’s sensibility on the reader’s most private space.” Which stories we tell, and how we choose to tell them, are all inherently political decisions. There’s also a great quote by Toni Morrison that says, “All good art is political! There is none that isn’t. And the ones that try hard not to be political are political by saying, ‘We love the status quo.’” If you want to write fiction that upholds norms, accepts society’s conceits and supports existing power structures, then that’s fine. I’m just not interested in doing that.

Fatma, in her early days as a prostitute, finds power in the veil. Can you comment on this?

Fatma was so much fun to write. She’s this irreverent, feisty old woman with a colorful past and a sharp tongue. I never knew what was going to come out of her mouth. She turns cultural tropes on their heads, dawning a headscarf only when it suits her. I think women in the West, myself included, sometimes see the veil as this great instrument of oppression, but Muslim women have a different story to tell. Fatma tells just one version of this story. There are many other, more devout, versions of it.

Fatma, the Kurdish woman, saves Lucine, the Armenian girl, and gives her a new life, even a new identity. Was this a common story? What do you think motivated these acts of grace? What separates someone like Fatma from someone who looked away from the genocide?

When you have state-sponsored denial, like you’ve had in Turkey for 100 years, it not only silences the victims, it also silences the heroes. We cannot celebrate the Turks and Kurds who risked their lives to help the Armenians, when the atrocity itself is being denied. There were many instances of Muslim Turks warning their Christian neighbors, hiding and feeding them at great risk. These stories are just as important, but you can’t tell one without the other.

There are several transformations in the book. Kemal turns into Eagle Eye, Lucine turns into Seda. The book ends with the image of a silk larva disappearing into its cocoon to await transformation. Do you believe people are capable of great transformation? Are they able to truly create new lives and transcend the nightmare of their pasts?

When you're writing about characters whose lives span 80 years or so, you can’t help but think about all the different people they’ve been over the course of their long lives. I love that Joan Didion quote that goes, “I’ve already lost touch with a couple of people I used to be.” I wanted to examine the slippery shifting quality of human identity. Also, there is so much power in the act of naming. One of the very first acts of colonialism, for example, is to rename the conquered peoples and landscape. The same is true in slavery. Some of my characters rename themselves as a way of coping with who they’ve become. Others are renamed by others.

Congratulations for being long-listed for the Center for Fiction Flannery-Dunnan First Book Prize. Is it true that "Orhan’s Inheritance" is the very first thing you’ve published?

Yes, it’s true. I don’t have an MFA. I don’t live in Brooklyn. (laughs) My journey to writing occurred organically. My entire life I’ve read voraciously and with great joy. I always kept a journal and wrote privately, but I never tried to publish anything until I had an entire novel on my hands.

What kinds of books do you gravitate toward? What are some of your favorites?

I just finished Laila Lalami’s "The Moor’s Account." It’s beautifully written and I love that she chose to tell the story from the point of view of the slave. I gravitate toward books written from the perspective of under-represented voices in history. I just finished reading Josh Weil’s "The Great Glass Sea." That book and Atticus Lish’s "Preparation for the Next Life" both blew me away. Some of my all-time favorites include Edward P. Jones' "The Known World" and Jeffrey Eugenides’ "Middlesex."

Shares