Coming down ...

Many people I know in Los Angeles believe that the Sixties ended abruptly on August 9, 1969 …

— Joan Didion, The White Album (1979)

In 1985, a creepy-looking LP with a burning jack-o-lantern-headed scarecrow on its cover haunted browser bins at hipper U.S. record stores. "Bad Moon Rising" was the first recording of note by Sonic Youth – a quartet of NYC art-school types whose brand of noisy, experimental rock seemed doomed to the cultural margins in the heyday of Michael, Madonna, and “We Are the World.” (“We’re just dying to be mass-marketed,” bassist Kim Gordon sarcastically told Creem magazine at the time.) And doom was "Bad Moon’s" métier. A somber soundscape of de-tuned guitars and stream-of-consciousness lyrics that starts faint and finishes triple forte, the album was a bad vibes extravaganza – an impressionistic document of Reagan era unease filtered through layers of feedback and postmodern detachment. Its one moment of true catharsis – musical, lyrical, spiritual – was about the Manson murders.

Coming down

Sadie I love it

Now, now, now

Death Valley ‘69

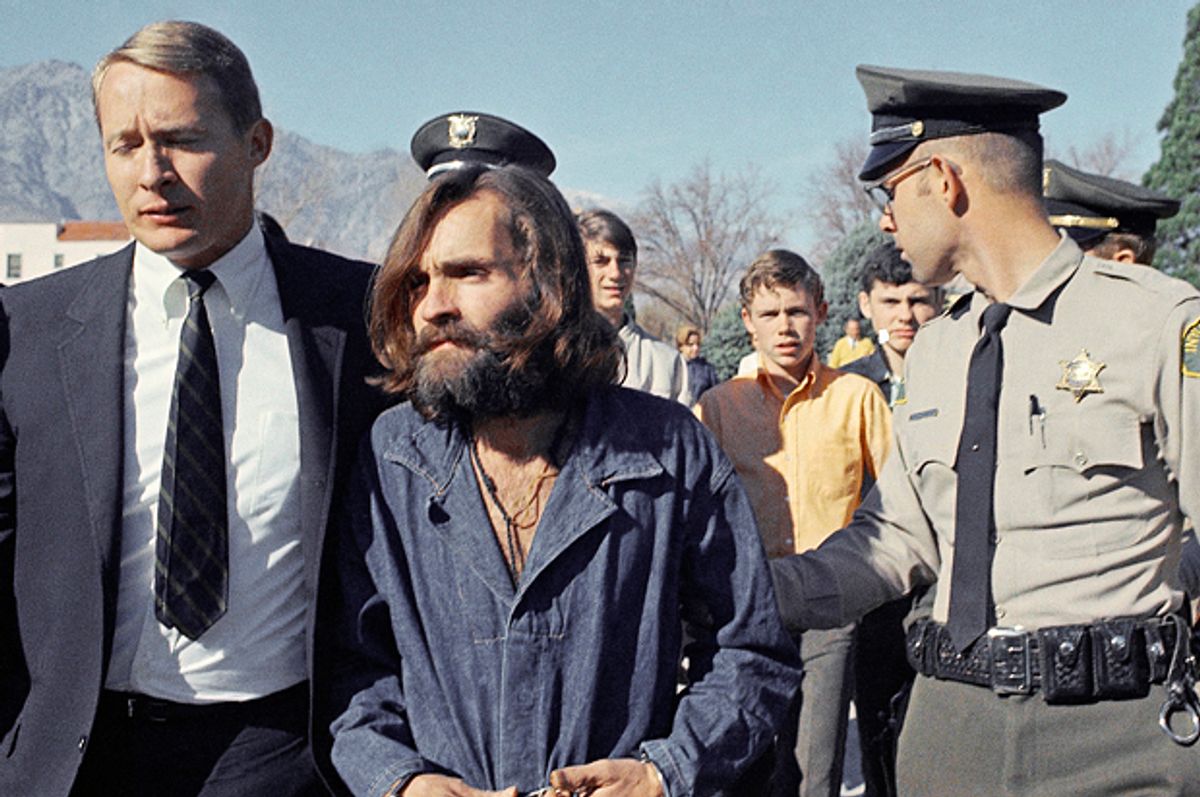

Between 1969 and 1972, Charles Manson and his followers (including Susan Atkins – the “Sadie” in Sonic Youth’s song) brutally murdered at least 11 people – probably a few, possibly many, more. These horrific crimes, replete with ritualistic overtones and bloody writing on walls, and the bizarre beliefs that motivated them – Manson’s messiah-ship, an impending apocalyptic race war, an Elysian hideout in the California desert for him and his nomadic Family – have been documented and debated in mind-numbing detail elsewhere.

But the Manson murders – especially the slayings of movie actress Sharon Tate (then eight months pregnant), four others, and businessman Leno LaBianca and his wife (“pigs” – or affluent, “establishment” types in Family parlance) on consecutive nights in 1969 – were also instant, macabre folklore, in part due to their myriad connections to potent cultural signifiers of the 1960s: Hollywood, rock 'n' roll, the ruling class and the counterculture. And Manson – a semi-literate, chronically incarcerated hood, seething with anti-authoritarian hostility, who used a domineering charisma to exploit hippie era youth’s hunger for gurus with deadly results – remains a cultural icon of enduring, if profoundly negative, resonance. This is the context for understanding both Manson’s impact on music and Sonic Youth’s song.

I was on the wrong track

We’re deep in the valley

Now deep in the gulley

And now in the canyon

Twenty-four albums and 30 years after "Bad Moon Rising’s" release, it’s common wisdom that Sonic Youth helped midwife a musical movement for a generation born too late for '60s rock or '70s punk, yet eager to find or forge rebellious sounds of their own in a decade of glitzy materialism and reactionary politics. Called post-punk, then indie, and finally – blandest of the bland – alternative, the burgeoning genre came to encompass everything from the aggressive hardcore of Black Flag to the moody jangle pop of R.E.M., and reached critical mass when Nirvana’s "Nevermind" (1991) finally toppled the old school rock of hair metal and Guns ‘N Roses. The new music was smarter, darker, more forward-looking, and Sonic Youth’s LP – though no masterpiece and several times bested by the band – was an especially grim manifestation of the new ethos (sample titles: “Ghost Bitch” and “I’m Insane”).

It also symbolically straddled those critical decades when rock was first taken seriously, the '60s and '70s, serving as a bridge between the values – roughly hippie and punk – each represented: it was beautiful and ugly, transcendent and nihilistic, California and New York. Older than many of their contemporaries, the band members had actual memories of the '60s (even of Manson: Gordon, who grew up in L.A., had an older brother who dated a young woman suspected by some of being murdered by the Family) and hands-on experience with punk at its most extreme.

She started to holler

She started to holler

I didn’t wanna

But she started to holler

Punk had made merciless fun of hippies – out of a need to destroy the old to create the new and in disgust over the perceived failure, with Reagan and Thatcher ascendant, of the '60s social revolution. (Despite mutual antagonism and contrary dark/light sensibilities, both subcultures were overwhelmingly left-ish in spirit.) With the '80s, this critical stance gained nuance: Bands gave sympathetic nods to '60s values (often via radical reinterpretations of iconic songs – e.g., Hüsker Dü’s electrifying 1983 remake of the Byrds’ “Eight Miles High”) but remained skeptical of the decade’s escapist tendencies – its preoccupation with what Sonic Youth guitarist Lee Ranaldo (born in 1951) once called “flowers and unicorns and rainbows.”

The wrong track …

The whole meaning of America is death.

— Thurston Moore (Sonic Youth, 1985)

In this context, revisiting Charles Manson – once described (by his own defense attorney) as a “right-wing hippie” – made sense. Loathed by conservatives, both as a killer and a sex-drugs-and-rock 'n' roll degenerate, his philosophy – autocratic, patriarchal, sexist, racist – was regardless far right of center. Equally despised by liberals, some leftists nevertheless portrayed him (mostly before his murder conviction) as a righteous revolutionary – most infamously, Weather Underground provocateur Bernadine Dohrn, who in a 1969 speech described the Family’s use of its victims’ own cutlery to desecrate their corpses with an approving, right-on-from-hell “Wow!”

Like many cultural icons (and all good boogeymen), Manson seemed to personify irreconcilable opposites – love and hate, peace and violence, freedom and tyranny – at a time when each was being redefined. This sociocultural dissonance still resonates because it remains unresolved. By the '80s, the Summer of Love was a distant memory and Reagan’s “Morning in America” was breezily obscuring the nation’s post-Vietnam malaise – even as his administration slashed social programs at home and armed right-wing militias abroad. For some, Manson became a canny symbol of the country at a schizoid impasse: an unseen (because locked safely out of sight) but ever-present reminder of unfinished business between right and left, old and young, hippie and punk, who terrified all because he blurred the differences between each.

Deep in the valley

In the trunk of an old car

I’ve got sand in my mouth

You’ve got sun in your eyes

If Hüsker Dü looked back to the '60s with bitter resolve, like post-punk folkies, the Sonic Youth of "Bad Moon Rising" (its title lifted from Creedence Clearwater Revival’s spooky, Tate/LaBianca-year Vietnam War song) did so with an irreverent glee worthy of the album’s grinning-pumpkin-head-on-fire cover. “Death Valley ’69,” "Bad Moon’s" explosive final track, wallows in the seediness of all things Manson with unclear motive and manic, musical overkill. Its perverse mix of taste (highbrow conceptual seriousness) and tastelessness (lowbrow scare-flick sensationalism) creates a tense art vs. trash dynamic that ultimately gives way under the sheer force of the music.

Despite the song’s atonal attack and subversive spirit, its structure is fairly traditional – a long, taut, near-monotonal midsection bookended by a thrashy power chord chorus, similar in structure to Pink Floyd’s 1967 psychedelic warhorse, “Interstellar Overdrive.” Musically, it delivers the cathartic goods the rest of the album’s slow crescendo promises. Lyrically, it strings together artless quotes and phrases related to the Manson murders, evoking their frenzied horror through allusion and indirection.

And you wanted to get there

But I couldn’t go faster

So I started to hit it

I had to hit it

Sung by guitarist Thurston Moore and guest vocalist Lydia Lunch – then a fixture of the New York underground and a pioneer of the city’s no wave style of noise-as-rock – her shrill and affected singing does the song no favors. While Moore sings “straight,” Lunch – part of a crowd of self-consciously transgressive artistes briefly aligned with the band early in their career (including arty pornographer Richard Kern, who made a forgettable video for the song) – sings in a self-consciously flat, pseudo-evil tone that threatens to tilt the song’s art/trash balance irreparably toward the latter.

With three decades’ hindsight one wishes the band had forgone Lunch’s histrionics for Gordon’s husky sensuality, but her status as Sonic Youth’s second lead vocalist/frontwoman wasn’t fully established in 1985. YouTube makes multiple live versions – of varying sound quality but sung by Gordon and Moore (and Ranaldo) – available for contrast. The best of these, though lacking "Bad Moon’s" conceptual framing, topple the art/trash scales altogether, revealing “Death Valley ‘69” as art rock in the best sense – a dark tone poem of layered guitars, pulsing drums and passionate vocals performed by a quintet of now middle-aged NYC art school types.

Deep in the valley …

I’m the last guy in line but I’ve got all the thoughts for the balance of order and peace with a one-world government if we are all able to survive.

Easy,

Charles Manson

(Letter to President Reagan, 1986)

In 1985, I was one year into my own art school education and Sonic Youth was a cool, new underground band. Most of my professors were aging hippies and/or '60s radicals, and as a punk enthusiast – raised on the Beatles but radicalized by the Clash – I both envied and (as was de rigueur at the time) disdained them. But I quizzed each, fascinated, about their memories and experiences of the mythical decade, and without exception each answered the question “What killed the '60s?” with the same response: “The Manson murders.” This uniformity of reaction was striking, as was their tone of reply, which ranged from elegiac head-shaking to sneering disgust.

As a cultural force, the anti-hippie hobgoblin has had a truly profound impact on our era. While the cumulative accomplishments of '60s social movements (civil rights, antiwar, environmental, etc.) undeniably altered the country, they also drove a rancorous wedge between those who applauded and those who condemned the changes. Consequently, a broad sense of loss and betrayal was felt by those deeply invested in the dream of a fully transformed society – a freer, gentler, peaceful ideal that never came to be, much mocked in subsequent decades by conservatives, realists and cynics. Many blamed this loss, literally or symbolically, on Manson and his execrable behavior. Superficially, this meant that the Family gave hippies, free love, communal living, etc., a bad name. But at a deeper level, it meant that their vilest acts, committed less than a week before the Woodstock Festival, caused a tear in the social fabric that may never be sutured: a legacy of reflexive doubt that routinely scorns idealism as hopelessly naïve – the stuff of “flowers and unicorns and rainbows.”

Before True Crime was a bookstore section or Amazon.com category, only a few such tomes existed. One of them, common in middle-class homes when I was a kid, was "Helter-Skelter: The True Story of the Manson Murders" (1974) by Vincent Bugliosi (with Curt Gentry). Written by the L.A. County deputy district attorney who tried and convicted Manson and four of his followers for the Tate/LaBianca murders, "Helter-Skelter" was a riveting piece of crime reporting and remains a classic of the genre. Forbidden access to it by my parents, I read it piecemeal, in surreptitious glances at paperback copies in stores, neighbors’ houses, or in my own home when no one was looking. I especially remember its black-and-white crime scene photos, with the bodies discreetly “whited out” (a respectful gesture unimaginable on the Internet, where ghastly photos – including of the Manson victims – can be found in seconds). "Helter-Skelter" fascinated and frightened me. A minimalist epigraph at the book’s front said simply: “The story you are about to read will scare the hell out of you.” It did.

The other Ur-text every Manson buff reads is "The Family" (1969) by Ed Sanders, a poet and member of the satiric '60s rock band the Fugs. Sanders not only offered a (highly critical) countercultural take on Manson, but also uneasily befriended Family members still living at Spahn’s Movie Ranch – the remote Hollywood film set and locale of a hundred B-movie westerns where the Family squatted for much of 1969-1970. Some of them were later convicted of murder. "Helter-Skelter" is the more trustworthy account, but "The Family" better evokes the weird, witchy tenor of the times.

I had to hit it …

This is the worst trip / I’ve ever been on

— The Beach Boys: “Sloop John B” (1967)

Both books offer vivid examples of the many serpentine links between the case and other '60s signifiers. Hollywood is one such link, but falls outside the range of this article. Suffice to say that the Manson saga is riddled with filmic connections – from its Benedict Canyon and Los Feliz crime scenes (the latter in a house once owned by Walt Disney) to victim Tate’s husband Roman Polanski’s homicidal and occult-themed films ("Repulsion," "Rosemary’s Baby"). Manson’s great scheme, after his 1967 release from prison, was to become some kind of star – preferably in music, but movies would also do – and he and the Family haunted film studios and stars’ homes throughout 1968-1969 to catalyze what Ed Sanders in "The Family" calls “operation superstar.”

But rock 'n' roll is where Manson’s malignant influence was most keenly felt and lingers still. Inspired in prison by the Beatles’ success, Manson – a competent guitarist and singer – became convinced that his meager musical skills and unorthodox philosophical insights (“No sense makes sense,” “Total paranoia is total awareness,” “You can’t kill kill”) would rocket him to stardom once he was released into the hedonistic wonderland of '60s California. His consequent failure – despite some surprisingly high-profile support in the music industry – played a critical role in his shift from sex-and-drugs messiah to vengeful maniac.

Brought to the attention of record producer (and son of actress Doris Day) Terry Melcher – who produced seminal folk rock records for the Byrds (“Mr. Tambourine Man,” “Turn! Turn! Turn!”) – Manson ultimately failed to impress the young executive and the rejection inflamed his insecure ego. Melcher lived in Benedict Canyon with his girlfriend, actress Candice Bergen, and when the couple moved out in mid-1969, their former home was leased to Polanski and Tate. On the night of Aug. 8, when Manson armed four followers and told them to kill the occupants of whatever house he sent them to, it was Melcher’s old place – now occupied by Tate and her houseguests (Polanski was in Europe on business) – he selected.

Manson met Melcher through the Beach Boys’Dennis Wilson in 1968, after the handsome drummer picked up a pair of female hitchhikers and drove them back to his Sunset Boulevard home. Unknown to the musician, both were Family members, and when he returned late that night from a recording session, he found his house swarming with nubile cultists and their guru-like leader. A dark period followed for Wilson, during which the Family moved in and helped themselves (over several months’ time) to $100,000 worth of his money and belongings, all the while pressuring him to boost Manson’s music career.

For a time, Wilson himself got swept up in the madness, promoting and recording the would-be superstar (he later erased the tapes, telling deputy D.A. Bugliosi “the vibrations connected with them don’t belong on this earth”). He called Manson “The Wizard” and admitted he was slightly afraid of him. Eventually he had the Family evicted and cut off contact, but extortion attempts followed. When Manson threatened his young son, an enraged Wilson – never one to shrink from a fight – “pummeled” him, according to Beach Boys collaborator Van Dyke Parks. Still, the musician increasingly feared for his life.

On a darkly humorous note, teenage Box Tops singer Alex Chilton – a forbear of alternative rock through his '70s band Big Star – crashed briefly at Wilson’s place during the Family’s residence there and was once sent by a Manson follower to buy groceries, out of pocket, for the household. “When I got back,” he later recalled, “they looked at the grocery bag and they said, ‘You forgot the milk!’ I said, ‘Aw gee, I’m really sorry I forgot the milk’ … By the time I got to the front door, they were standing in the doorway, blocking the door, and they said, ‘Charlie says go get the milk.’ The vibes were kind of weird.” Chilton left soon afterward.

Part of Manson’s animus toward Wilson stemmed from the musician’s adaptation of one of Manson’s own songs for the B-side of the 1968 Beach Boys single “Bluebirds Over the Mountain.” The move – ostensibly part of operation superstar – angered Manson because Wilson substantially rewrote the song in an attempt to make it commercially viable. (He also took sole compositional credit – a mercenary but probably fair action in lieu of the strain the Family put on his bank account.) Originally an acid-fried anthem to ego death with sadistic overtones called “Cease to Exist,” Wilson changed “exist” to “resist” and reshaped it into an unlikely love song called “Never Learn Not to Love,” replete with chant-like but appealing Beach Boys harmonies.

Cease to resist, come on say you love me

Give up your world, come on and be with me

There are few creepier cultural artifacts of the '60s than this admittedly not great but still haunting song. Recorded during a rough patch in the Beach Boys’ career, when their resident songwriting genius – Dennis’ troubled brother Brian – was withdrawn and inactive following the traumatic collapse of his psychedelic magnum opus, "Smile" (co-written with Parks and finally completed and released to ecstatic reviews in 2004), the record marked the only time before his final incarceration that a Manson song saw wide release. It was even performed on “The Mike Douglas Show.” Wilson croons the song with stoned sincerity, in the same slightly raspy voice he gave “Forever” – a romantic ballad and minor Beach Boys hit in 1969.

Submission is a gift, give it to your lover

Love and understanding is for one another

Manson needn’t have fretted over his potential big break, as the single flopped. But the demands for money continued, their ante raised by symbolic .45 caliber bullets Wilson received, and the cumulative intimidation took a toll. The drummer found himself in a state of constant paranoia (or “total awareness” in Family parlance) – an anxiousness that would not abate until Manson’s arrest on suspicion of murder in late 1969.

I’m the luckiest guy in the world, because I got off only losing my money.

— Dennis Wilson (1970)

This piece originally appeared in Murder Ballad Monday/SingOut!

Shares