Tumuhimbise Norman is one of those relentless characters. You know the type. He’s the kind of activist who will keep pushing and pushing — not minding the risks or burdens — until his demands are met.

Tumuhimbise Norman is one of those relentless characters. You know the type. He’s the kind of activist who will keep pushing and pushing — not minding the risks or burdens — until his demands are met.

Over the course of several months, Norman and his colleagues plotted a successful attempt to sneak yellow-painted pigs into Uganda’s Parliament in protest of greedy politicians. Since then, he’s been hopping between prisons, courts, talk shows and the streets without any sign of being deterred.

On August 19, Norman and his associates with the Kampala-based youth activist group The Jobless Brotherhood, or TJB, staged another dramatic display by painting their iconic guerrilla piglets many colors and setting them free in the city. They wanted to make it clear that the opposition politicians, symbolized by multiple colors representing various political parties, were doing just as little as those from the ruling party, which sports yellow attire.

Attached to the pigs was a “last letter to government” directed toward the nation’s dictatorial leadership, in which TJB threatened to initiate a period of civil disobedience in response to the failure of parliamentarians to pass electoral reforms. “We had given you a little benefit of doubt, thinking you would come back to your senses,” read the note. “We may resolve to have temporary instability if it can guarantee permanent stability of our motherland Uganda.”

The very evening these messenger piglets were scattered in the city, Norman disappeared.

Activists, organizers and civil society organizations went into crisis mode, running around from one police station to the next to inquire whether Norman had been detained there. Some of his associates were facing threats and were advised to sleep in guest houses in various places throughout the city so as not to be snatched by the plain-clothes agents frequenting their homes.

Through Whatsapp and Facebook correspondences, a press conference was convened within 48 hours, through which the public was asked to provide any information that may lead to the recovery of Norman — or at least his corpse. The rumor began surfacing that Norman was abducted near his home by disguised agents of the Special Forces Command, an anti-terrorism division of the Ugandan military that received counter-terrorism training with the U.S. military.

The kidnapping was totally believable, as the Special Forces Command has a reputation for harassing politically active youths and torturing those who criticize President Yoweri Museveni’s three-decade military regime. A feeling of defeat trickled around Norman’s social circles, as he had long been hailed as a kind of indomitable force on the frontlines of political change.

Nevertheless, total despair had not yet set in. TJB members visited Norman’s wife, sister and two-year-old daughter, asking them to join a public effort to make an inquiry concerning Norman’s whereabouts at Kampala’s Central Police Station, which they agreed to do. This new search party bombarded their media contacts, which put the police in a situation of crisis when Norman’s wife began crying and begging them to return her husband’s body for a proper burial.

In a typically unprofessional move, the Ugandan police detained the coalition. Their phones, however, were not confiscated, so the detainees were able to use Facebook to call for immediate outside assistance. After a few hours, police realized they were getting too much attention and released the group.

Yet, Norman’s family and colleagues were nowhere closer to locating him. There were talks about organizing an interfaith prayer, but those plans were only inching along slowly. Something more drastic and alarmist had to be done. Every second Norman was gone increased the likelihood of finding his remains washed up on the shores of the Nile River.

Almost a week after Norman’s disappearance, social media coordinators for various youth groups in Kampala announced that Norman was dead. A picture of his face was posted on Facebook, crossed out with a red “X,” and accompanied by a few words explaining how he had been killed by “Dictator Museveni.”

This forced the state to act. The only way it could refute allegations of murder was to produce Norman himself. Within a few hours, Norman was pushed out of a white double-cabin vehicle in the late hours of the night. He stumbled home in terrible condition, dehydrated and unable to talk.

Norman was immediately rushed to obtain proper care. Medical reports indicated he had suffered ocular damage. There were chemicals still dripping from his eyes, which had also been pushed deep into their sockets. His spine was misaligned, and he suffered a visceral rupture. Doctors put him on a drip to replenish his body with the necessary fluids.

“I blacked out as soon as I was forced into their vehicle,” Norman explained to me during a visit I made to his home after he was well enough to talk. “I woke up some unknown amount of time later in a completely black room where I was repeatedly asked the same three questions and tortured for my responses to them.”

The first thing his captors wanted to know concerned the funding sources behind TJB. Norman asked those interrogating him whether they had seen the activist group build any buildings or start any businesses in Kampala. After all, piglets can be purchased for less than $20 in the local market. Very little capital was needed to organize, Norman explained, so there were no major funders behind the movement.

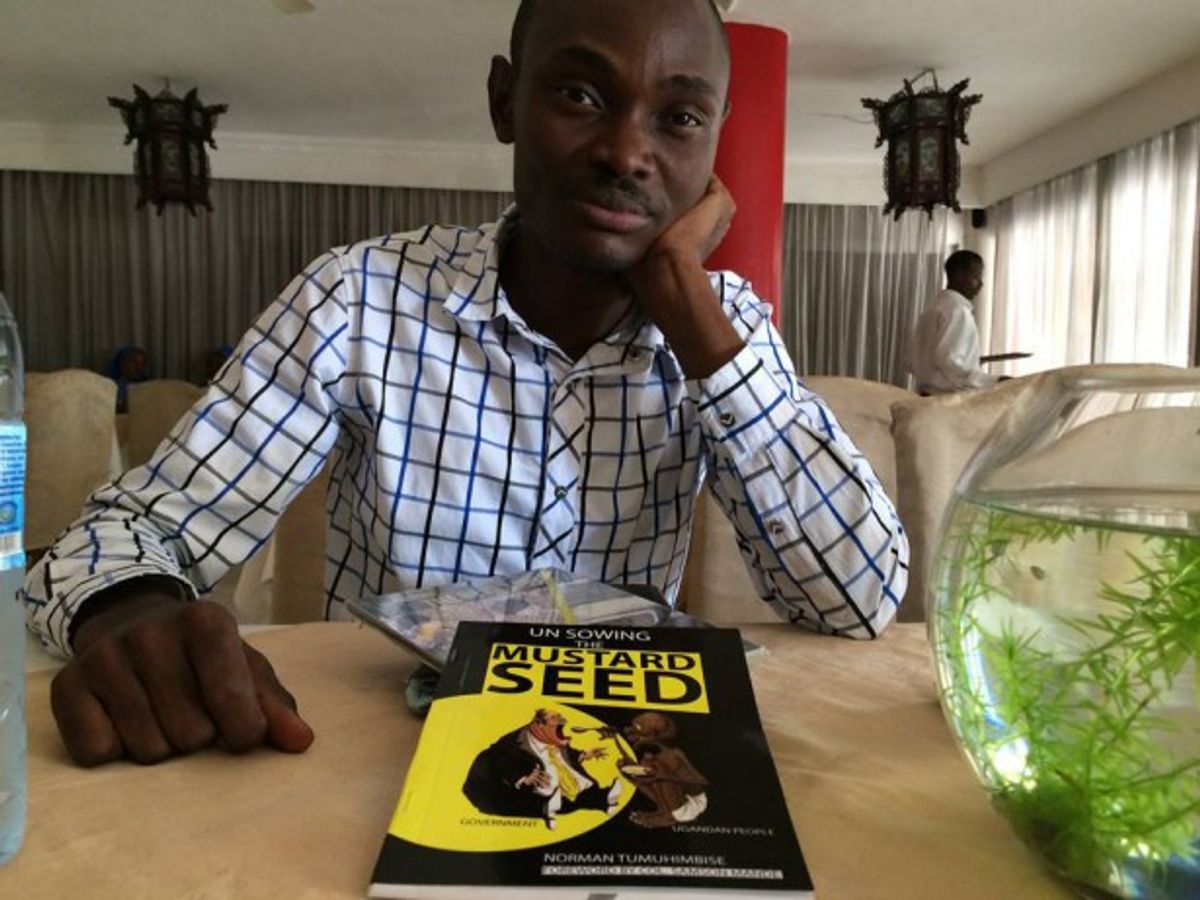

Norman’s torturers then questioned him about his recently published book, “Unsowing the Mustard Seed,” which chronicles Museveni’s crimes against humanity in his quest to take power in the country, as well as Norman’s personal encounters with poverty and political oppression. (I also contributed a section to the book on the strategic benefits of nonviolent tactics and movement-building in Uganda.) The book’s title is a direct challenge to Museveni’s own book “Sowing the Mustard Seed,” in which he describes how he became Uganda’s successful liberator in the mid-1980s. The interrogators asked Norman where he had obtained the information in his literary rebuke. He explained, truthfully, that there were some former associates of the president who had defected and offered their stories to him.

Finally, the captors asked Norman about the campaign of civil disobedience TJB intended to launch, as indicated in the letter affixed to their pigs. They accused Norman of stockpiling weapons to initiate an armed rebel movement. “I told them that even if I die, the cause will never die,” Norman later explained to me. “There are more than 1,000 people ready to champion the same causes with the same tenacity. This response won me heavy beatings and slaps, but I just kept asking them whether they wanted to hear answers that pleased their ears or if they wanted to hear the truth.”

Norman’s resolve is clearly not shattered. He and his associates were busy brainstorming other ideas that could pester their dictator, which is an especially useful approach in sub-Saharan nations that tend to have patriarchal and ageist mainstream cultures in which old men in positions of leadership are not to be confronted or even questioned by females and youths.

Supporters across the nation and abroad are currently advocating for an international dialogue concerning Norman’s abduction and torture. “We want to see foreign countries blacklist our leaders who are, at best, complacent with the present conditions under which activists and advocates like me are suffering,” Norman said. “In many cases, they are the ones perpetuating injustice directly. They have bank accounts in foreign countries and travel there for both business and vacation. They have no interest in improving their own country. Let the foreign countries block them from entering so that they learn a lesson.”

“Unsowing the Mustard Seed” is now available online, and TJB intends to continue promoting the book to generate a cash flow that can support their activities. “People are wary of just making contributions, especially if they don’t know us,” said Norman’s fellow TJB coordinator Mayanja Robert. “Now that we have something for sale, it can generate some financial support for us and the buyer can go home with a book that sensitizes him or her on the true stories of Uganda’s political history.”

Norman’s “resurrection” is no doubt a win for TJB and other progressive groups throughout Uganda, but the activist continues to face challenges. His landlord of several years finally succumbed to the pressure from authorities, coupled with an alleged bribe of a few thousand dollars, to evict Norman’s family by the end of this month. Norman is currently seeking civil society stakeholders who can help his family find a secure residence that can also accommodate other at-risk activists and organizers from time to time.

Although Norman was repeatedly told by his captors that they could snatch him any time they needed him, he seems to almost disregard this threat. To see Norman emboldened by his recent experiences is something that will kindle the flames of change in young Ugandans across the nation. They’ve already raised him from the dead. There’s no telling what other nonviolent miracles are in store with elections approaching early next year.

Shares