If you think you feel pressured to watch all of the good TV out there, imagine having to watch for a living. It’s impossible to keep up — and here I will confess to having skipped the ratings juggernaut “The Walking Dead.” I can’t stomach zombies; I made it through about four episodes before I gave up. It wasn’t until I saw the movie “Requiem for a Dream” that I realized why. Now I know there are two types of characters on-screen I can’t watch—zombies and drug addicts. The terrifying, dark eyes, the sagging limbs—to me, they look precisely the same. They look like my mother.

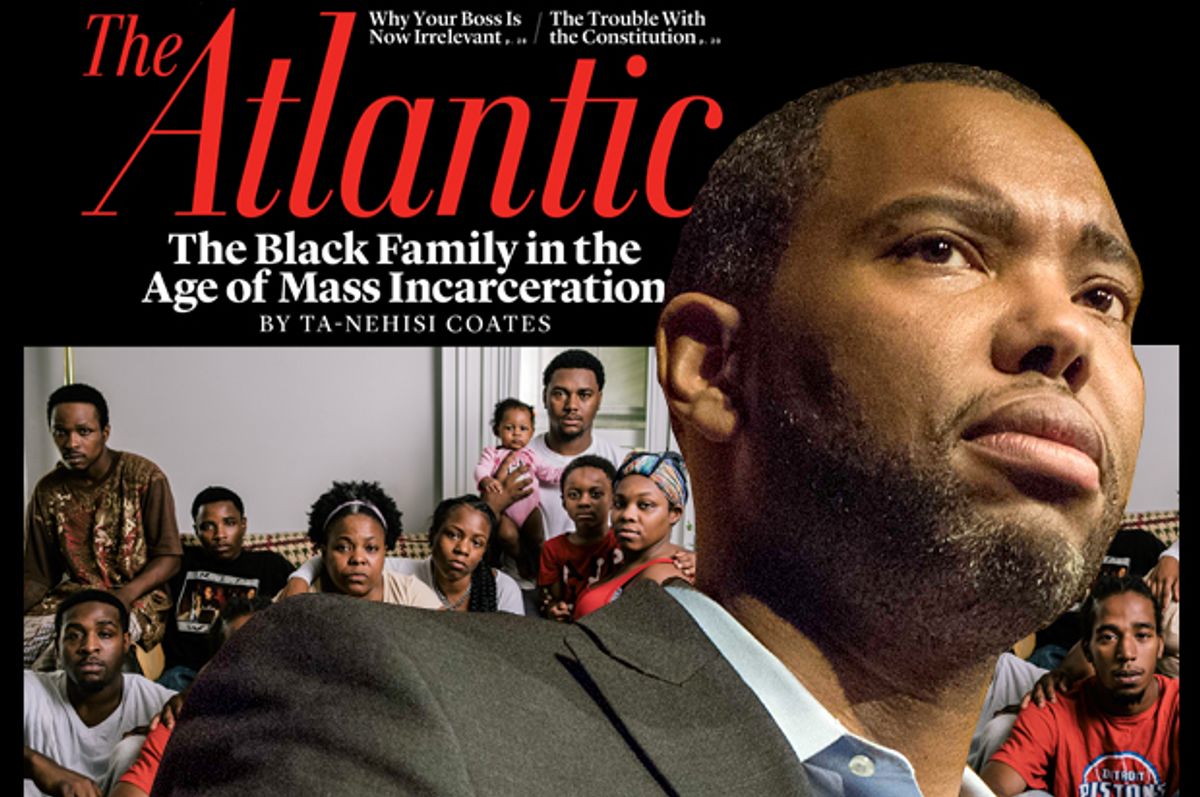

Or, I should say, they look like how I imagine my birth mother looked. Unlike my older siblings, I don’t have a strong recollection of our mother before she turned us over to the state of Massachusetts. And up until this point, I’ve never understood her, or the very large Houston family who looked on silently while she gave up six children, all under the age of 10. The only reason I can even begin to understand what happened to us now is because of Ta-Nehisi Coates’ recent article for the Atlantic, “The Black Family in the Age of Mass Incarceration.”

Before that, an article about a possible end to the war on drugs and “The Wire’s" David Simon’s concerns about decriminalization already had me rethinking my biological family. My adoption at the age of 7 had, among other things, granted me the privilege of not having to consider certain things about the world I came from — I’d dodged that bullet. But today, the hypothetical question of whether my life and the lives of my five siblings would have been different in a society that treated drug users differently seems relevant. Coates argues that imagining such a world demands that we go far beyond the question of decriminalization. Legalizing marijuana is fine and good, but in no way does it acknowledge the centuries of work that went into the mass incarceration of black families and the systematic destruction of families like mine.

One of the biggest takeaways from “The Black Family in the Age of Mass Incarceration” is that it is no accident that the black family has, in many respects, been destroyed. Slavery may have been abolished in 1865, but various forms of unfreedom—the most successful version being mass incarceration—exist and operate today. Coates uses the narratives of individuals like Tonya (a woman who became an addict after years of abuse from her biological family and foster parents), and families like Patricia Lowe’s to show how mass incarceration is both a political and personal attack against the black family—a direct descendant of slavery and Patrick Moynihan’s 1950 report “The Negro Family.” What that means for many people like me is that there is now a piece of writing that functions as the beginning of an answer to a question all kids who have been in the system have asked: “Why did my family abandon me?”

Coates offers up some statistics that help illuminate things: “From the mid-1970s to the mid-’80s, America’s incarceration rate doubled, from about 150 people per 100,000 to about 300 per 100,000.” These numbers refer to people like my biological mother’s father, who was in and out of prison countless times during this time. “From the mid-’80s to the mid-’90s, it doubled again,” he writes. During these years, at least one of her older brothers was incarcerated, too. My mother would go on to serve her own time as well. For me, these statistics offer up a helpful framing for the world that was in place in 1988 when Crystal Houston called the Department of Social Services in Boston and asked them to come pick up her six children.

***

If you ask my mother why she turned her six children over to the State, she will never speak of her struggles with drugs, and she will certainly make no mention of her being a victim of a system meant to criminalize black women like her and black men like those in her family, and those with whom she chose to create families. She will tell you one true story, and she will tell it over and over again, with the occasional variation in detail.

When she was 23 and pregnant with her twins, her mother went missing for a couple of days. My grandmother had recently divorced her husband, my mother’s stepfather, and remarried. My mother grew worried and, along with her siblings, went looking for her mother. She visited the shoe store owned by her stepfather and mother. Upon finding him there, she asked if he knew where her mother was. She’ll tell you she saw something in his eyes, and in a panic, began searching through the store, and went into the back where she stumbled upon her mother’s corpse. The woman who’d always been there for her, the woman who never made her feel judged or like less of a person, the one who was helping her raise her children, had been stabbed to death in what a judge would later rule was a crime of passion. This is why she couldn’t raise her kids, she’ll tell you.

She won’t tell you that she’d already developed a drug habit. She won’t tell you that her oldest daughter (still well under the age of 10) had already grown accustomed to being left alone for long stretches of time—sometimes days—with her younger brothers and her baby sister. She’ll just tell you that finding her mother’s body, while pregnant with the twins, was too much for her to bear. “I knew I was going someplace dark after that, and I couldn’t take you all there with me,” she once told me—the only allusion to her addiction I’ve ever been able to decipher in our conversations, which are few and far between.

The words of Margaret Garner, the enslaved woman who became the inspiration for Toni Morrison’s “Beloved,” are the first words Coates uses to begin his historical narrative: “Never marry again in slavery.” Garner was a mother who also had no desire to take her children where she was going. And while the connection between these two women might seem loose, I can’t help but marvel at how their boldest and most terrifying personal choices were rooted in political doctrine against the survival of the black family.

My mother may not have been fully aware of it, but in the ‘80s, she was living in an era of unfreedom as well. That she was going to further shackle her wrists and ankles together with crack cocaine and heroin was, for her, all the more reason to find a different space for her children. Like Garner, she wanted a better life for those innocent bodies she’d brought into circumstances that would surely hinder them. Unlike Garner, she didn’t attempt to kill us. She probably thought that she was saving us — and in some way, I know she did. But the system, as Coates explains, isn’t designed to save individual members of the black family, no matter how well-meaning one’s parents might be.

My two oldest brothers were separated from my sister and me, and put into a foster home. The twins went to live with their father and his family. My sister and I were separated after just one year together, when our foster parents believed she was showing signs of difficulty. Neither of us remember it this way (I have memories of her pinching the hell out of me, like big sisters have been doing to little sisters the world over, since the beginning of time), but if she showed any signs of anger or difficulty, it was certainly easier to move her into an institution than to get her help, so that’s what they did.

When my brothers became too old or too difficult (or too much like preteens, or too black—whatever they were guilty of), they were also separated and sent to various group homes. It is a well-known fact that these places are, for many young black boys, a fast-track to jail and prison. After turning 18, the boys and my sister were all released from the State. All of them, including the twins, at some point or another, found their way back to our birth mother.

Both of my older brothers and at least one of the younger have served time, a fact that comes to mind when I read sociologist Devah Pager’s quote in Coates’ piece: “Prison is no longer a rare or extreme event among our nation’s most marginalized groups... Rather it has now become a normal and anticipated marker in the transition to adulthood.” My oldest brother is inside right now. He’s been selling drugs for many years, and was recently caught with a large amount of heroin. My sister told me a story I still cannot believe—that he once sold to our mother. It’s probably true.

If it is, Coates tells us, then this is also proof that the system is working just fine. Indeed, it may be an indictment of my brother’s character, but it’s also proof that some black men might become so destroyed by a system that set out to do just that, that they’d sell drugs to their own mothers. But this knowledge of a political system at work — at work when the men are in prison, and still at work when they are released — does not take away from the fact that this is personal. This is my family, my blood.

***

What’s strange about having been adopted by a historian is that even the intelligent, politically and socially aware mother who raised me would get angry with my biological family. Before she passed away when I was 15, every once in a while she’d go on a mini-rant about how she couldn’t comprehend an entire family letting four kids get swallowed up by the system. When I was 13, I met my biological father at my sister’s birthday party in Boston. My mother was furious that this had happened without her permission. How dare these people try to come back into your life after all these years (and, subtext: after all her hard work earning my trust and love). She was the smartest woman I knew, but looking back it seemed that even she couldn’t see how my blood family was not really flawed, but was instead a shining example that the American system was working.

How could a whole group of children be lost to a system? Easily. Throw in a handful of incarcerated black men, a birth mother with better access to drugs than grief counseling, and a father who hadn’t even been made aware of my existence until I was already adopted (and who had his own struggles with drug abuse), and you have the Houston family—the product of a finely tuned environment.

There are personal explanations for how my birth mother became a 23-year-old living in Brockton’s Southfield Gardens housing projects with four young children and a set of twins on the way, but there are political explanations as well. As the child of an impoverished black family in the ‘80s, according to the political forces outlined by Coates, that is precisely what she was meant to become. In the same way, she was also meant to become an addict, one who would go on to prostitute herself for money to support her addiction, and would then be arrested on such charges. She was born into—then brought lives into—a system designed to foster this.

In taking on the prison system, Coates’ work shows us a world where laws, since the drafting of the Constitution and the Fugitive Slave Clause, were literally made to break us; drug wars were declared and funded by government administrations who, either openly or behind closed doors, declared their hope for the end of the black family or, as President Nixon did, an end to those “criminal elements which increasingly threaten our cities, our homes, and our lives.”

My mother may have grown up in the projects and may have become accustomed to her loved ones—those so-called “criminal elements”—going in and out of jail and prison, but she also grew up in a two-parent home, headed by her mother and stepfather. The parents who raised her were, to my knowledge, loving and fairly stable business owners. Although my mother was young and clearly troubled, she had a lot of help from my grandmother, a devout Catholic who did not believe in abortion, and would not permit my mother to have any, while raising her children during those first few years. My mother was loved, but because she still existed in an environment geared more toward her failure than her success, that love wasn’t enough.

Perhaps she sought to fill those holes created by her biological father’s constant incarceration with the father of my oldest sister, and then again in the father of my oldest two brothers. And did the same, again, with my father, and again with the father of my younger brothers. For years I saw her as ignorant, disgusting, irresponsible and weak for deciding to have so many lovers and so many children—decisions I saw as the beginning of the end of a chance for my siblings and me to have a “normal” family life. But Coates tells me, as no one else ever has, that these choices were not merely in the hands of my mother. These decisions were part of a greater design.

***

Twenty-seven years since we lost our first family, my two older brothers, my sister and I have all gone on to create our own families in this age of mass incarceration. It’s telling that not one of us has created a nuclear family consisting of a father (husband), mother (wife) and child(ren). While some of my siblings have attended college, I’m the only one to have graduated. We’ve all been on public assistance at one point in time, and I believe we — unsurprisingly — all suffer emotionally from the abandonment of our birth mother.

Speaking for myself I can say that, because of my experiences, the word “family” has an effect on me similar to those “Walking Dead” zombies: My stomach turns and I try to tell myself, sometimes, that it isn’t a real thing. Family isn’t real. That even as a mother myself, I don’t always see the value of the family unit because of my overwhelming disappointment in my first black family, is proof that a system designed to dismantle the concept of the Black Family—which has been deemed, in many ways, worthless—has been highly effective.

That I had to fact-check many of the details in this piece with my older sister, the only blood relative with whom I have had fairly consistent contact, is also proof that this system has been highly effective—but isn’t infallible. In spite of it all, we laugh as much as we cry about what happened to us, partly because there are some pretty hilarious memories too (like how my foster parents let me wallpaper my room with NKOTB posters, or how—true story—this one prostitute who knew our mother got her nipple bitten off in a fight). But our relationship also highlights the fact that, even when I’ve had access, I’ve cowered from contact with my biological family. On one hand, it’s a defense mechanism and survival tool. But this personal fear is also political—a symptom of the rhetoric of white supremacists like Hinton Rowan Helper, who helped create the myth that gets its very own chapter in Coates’ work: I too came to believe that there was a “crime-stained blackness” inherent in my family. Whether I wrote them off as “ghetto,” or “hood” or “ignorant,” I did so with the faulty assumption that they chose their quality of life—they chose, in some way, to remain in poverty, addicted to drugs and/or incarcerated. That I held on to these beliefs tightly, and that it took the work of a scholar to loosen that grip, is further proof that white supremacy is a hell of a drug, and not one of us is immune.

When I think about what the State did with us, I think of that quote from Belgian King Leopold II at the 1876 Geographical Conference on Central Africa: “I do not want to miss a good chance of getting us a slice of this magnificent African cake.” We, my siblings and I, were our own little continent, divvied up for the taking, though not worth near as much as that magnificent African cake proved to be. It reminds me that even when there is public, historical record of a body of land or a body of people being sliced into pieces, the world can go on as if it never happened, and those in power—those Clintons, those Bushes—can continue to reign as if they never played a hand in the damage done.

Coates’ piece ends with a return to his call for reparations—repair for the damages done. Like him, I can’t help but ask who will pay for the damages done to the families highlighted in his piece? The Tonyas, the Lowes, the Newtons? And who will pay for what happened to the Houstons, the Davises, the Wrights—the four of us who went through DSS? The youngest two may have evaded one system by going to live with their paternal family, but how much better was it, in the end? Unfortunately, I wouldn’t really know — I haven’t met my younger brothers yet.

Most likely no one, much less the American government, will ever pay. But the political acknowledgement of this failed system is not enough. An admission that the war on drugs and the war on crime failed is not enough. And yet, I fear that it’s the most I’ll see in this lifetime.

While the American government may never do its part, I will do mine. I’ll no longer place the entire blame of the early childhoods my siblings and I lost, and the ongoing, unfolding results of that loss, on the family that never came to save us. That they were addicts, or grief-stricken, or incarcerated, or traumatized by the loss of their own family members to incarceration or drugs, or depressed and distracted by the realities of their own surroundings means that they were, like countless others, too busy trying to save themselves.

And although they are not absolved of all wrongdoing and all mistakes, my broken black family deserves my understanding — and forgiveness, too, though I haven’t completely reached that, yet. In addition to providing us with a sharp historical, social and political perspective on the era of mass incarceration, Ta-Nehisi Coates gave me a necessary insight to the judgments I cast against a family that America had decided was never meant to survive or thrive. And even as I am eternally grateful for a second family and for second chances, and for the family I’ve started myself, the untold stories of my first family continue to haunt me. It’s not just my blood, but the potential of a people who might have flourished in a system designed for them to do so, that I will not stop mourning.

Shares