In the fall of 1999, at the age of 25, I retreated into solitude in a house in northern Vermont, at the dead end of an unmaintained dirt road. To get there, you passed the barn and blue silo of a dairy farm, snaked past a few scattered houses and trailers, then followed deeper into the woods, until the road dwindled into what seemed only the ghost of a road—the weeds between the two ruts taller than your car. A small meadow opened on your left, and beyond the meadow was the beginning again of forest, with little promise of a house at all. From there, just inside the weather-beaten fenceposts, you walked. And at the bottom of the steep grade, with its sky-blue paint flaking, its lines badly canted, sat the two-story house, like a sunken ship.

I brought no computer, no television, no cellphone. There was a land line, which rang maybe twice a month, so a wrong number was an event. The house had running water, electricity, and a woodstove. I bought six cords of firewood to get through that first winter; otherwise, my expenses were just food and propane for the hot water heater, and it was easy to live off my savings from teaching. For provisions, about twice a month, if the road wasn’t snowed in, I drove to the little market in Barton. For daily activity, I woke with the sun, walked or snowshoed in the woods surrounding the house, and kept the fire going. Sometimes I wrote poems. It became second-nature to live without an outer life—so much was happening inside me. One winter deepened into two. Even keeping a journal came to feel strange—as though I was trying to corral the wind, the snow, and the stars into the shape of a man.

When I left for the woods, friends compared me to Thoreau. Culturally, the comparison may have been apt. Thoreau went to the woods “to live deliberately” largely as a response to the second stage of the Industrial Revolution, when the familiar dimensions of time and space—of how long it took news to travel from New York to Boston, for instance, or how long it took to manufacture a shirt—were contracting. The Information boom of the late 1990s had a similar effect: cellphones, handheld computers, social networking—all of it changed not just Americans’ daily lives but our sense of ourselves in time and space, how alone or un-alone we are, our sense of privacy and pace.

But my move to the woods wasn’t a cultural experiment. It was a personal necessity. Five years earlier, during my junior year at Harvard, a freak accident had blinded me in my right eye. During a pick-up game of basketball, as we scuffled for a rebound, a boy’s finger hooked behind my eyeball and severed its attachment to my optic nerve, the cable that connects the eye to the brain. The pain was unlike anything I’d ever experienced. There was nothing the doctors could do. The loss of vision to my right eye was permanent.

With vision in only one eye, there’s no stereopsis, no depth perception. And without depth perception, the world looked simultaneously flat and permeable, like I’d crossed the threshold into a fantasy land, where nothing was solid, including my sense of myself. I felt as though I’d been caught with a secret I’d forgotten I was carrying. I’d been harboring a double life—one for everyone else, and a different one for me. The one for everyone else was slightly too independent for my parents’ taste, but he was a son to be proud of—a Harvard student, a fine young man, one who looked like Bob Dylan circa 1964, before Dylan went electric. Probably a future lawyer. At worst a journalist. And thanks to him, I didn’t have to worry about the hidden part of me, the part that crept out while I was reading poetry in my dorm room or walking alone by the Charles River, the part whose deepest sense of meaning came from something I couldn’t articulate, even to myself.

To compound my disorientation, after the blood dissipated, my eye looked as it always had. The gap between how I presented myself and how people saw me widened into a gulf. And the track I’d been on, which headed toward law school, and the old track of my thinking, which often allowed the comfort of achievement to substitute for meaning, and which had kept me from entering into the passing landscape to forge my own values, became impossible to live by.

I went to the woods because I needed to live without the need of putting on a face for anyone, including myself. I needed to be no one, really, while carrying the hope that my particular no one might feel familiar, might turn out to be someone I had known all along—the core of who I’d been as boy, the core of who I might become as a man. My plan was to find that core by returning to moments of wonder, of pure attention, to become aware of myself by the quality of my perceptions rather than by others’ perceptions of me.

In the woods, I developed my own rituals. In fall, day after day, I crouched in the wet grass with the snails, trying to see as slowly as they seemed to. In winter, day after day, I snowshoed into the snowy trees and watched for chickadees, learning to let my eyes go soft, open to movement, rather than stalking branch to branch. I was learning to trust a more generous reality, one that allowed for all I could not see and all that could not be seen in me, one that didn’t need hard lines or tracks to make me feel oriented. I became aware of a kind of spiritual responsibility—the need to go far enough back so there would be nothing else waiting behind, the need to touch the hard edge of reality, and begin from there. For the deepest moments in life—for love, for prayer—we close our eyes. I wanted to see that way, always, even with my eyes open.

Time began to change. There was no clock in the house. No sense of time other than the daylight through the windows and my own sense of pattern—finding my hand on the kettle as it began to tremble, or stepping outside to find the sun a white hole above the highest spruce. I’d never given it much thought, but now clock time seemed bizarre, like we’d domesticated the Earth’s motions, housed it in convenient cages, harnessed it as a farm animal to help with our daily work. No longer would I slip the turning of the Earth from my wrist.

I had almost no interaction with people. I had an agreement with a handyman who lived by the Canadian border—when there was a bad storm, he would plow. Sometimes he came; sometimes he didn’t. I never called. When he did arrive, a few words about the weather felt like a heart-to-heart. Likewise, when I’d stock up on soup and bread in town, just seeing the cashier up close—the oval shape of her face, the almond shape of her eyes—felt like a revelation. I was what she was: human.

Deep in that first winter, I couldn’t imagine returning to Boston. The loneliness had mostly faded—it was just a fact, a part of the weather. I felt at home, in a habitat that fit with my senses, as though some membrane had been dissolved: I was back in the world, rather than outside it. I even began to feel closer to friends. On rare phone calls from my friend Ray, who was in med school in New York City, I found myself listening the way I’d learned to watch for chickadees—not chasing, just picturing everything and letting my mind’s eye go soft, until there was movement in the picture, until the doubts Ray was confiding to me became clear.

But by winter of the second year, there were warning signs. I ate fewer meals. My snow-pants wouldn’t stay on my hips. I didn’t know it then, but I was down to 120 pounds, as opposed to my normal 155, which at 5’10’’ was already slender. The world beyond the woods kept pulling farther away. When the phone rang, I didn’t answer. It seemed my body was falling and filling with the drifting snow, filling and falling with the changing wind. I felt as though my body had become an open doorway without a house, a doorway that was just a means of awareness for everything passing through it. I no longer spoke. No longer thought, other than in a kind of humming. Images drifted through me the way the reflections of migrating birds drift across a pond. It seemed the day was making itself aware of itself through me. That was all. I told myself this was progress. I was losing surfaces, losing form, which meant I was getting down to rock bottom, to something essential.

But occasional migraines pushed from behind my eye, pushed liked a hand reaching for me from out of my past. Which is what brought me out to the field that night. After vomiting in the snow, I lay down on my back. I could see the North Star, the bow and belt of Orion. I could feel the cold seeping through my jacket, seeping into my skin. I was cold, but also warm, also burning, and I lay there until I couldn’t tell what I was, and my eyes closed.

I dreamed I had killed someone, but I couldn’t remember who, I just needed to keep the body hidden. The body was in a locker in my high school, and when I opened the door, the face was my own.

By the time I woke, it was impossible to move my fingers, my toes. Orion was on the far side of the field. Eventually, back at the house, I struggled to remove my clothes. Kneeling in the shower, I found myself crying. There was no other rock bottom, no other hard reality. I needed to feel myself against surfaces, to find the shape of what was inside me against something outside me. I needed people, I needed love.

My mom and dad’s faces appeared in front of me in the pebbled water. I apologized to them for everything I had put them through. In my sporadic calls back to Boston, they’d reasoned, pleaded, chastised. They’d grown angry, defeated, resigned. They did not need to know what had driven me here, I realized, they only wanted me back. And not the golden boy version, or the shamed prodigal son, not some version they even particularly understood. They loved me with the same love I’d found in the woods, a love below all surfaces—it just wasn’t anything they could express, just as it wasn’t anything I could express. But I knew the invisible was inside them, too.

That next morning, curled by the woodstove, I felt something I hadn’t felt for a long time. A desire for the future. I didn’t know then that just at the time I had learned to slow down, the world had learned to speed up. But I did know that good days might be ahead, days with other people. Days I might allow myself to trust.

Thoreau wrote Walden “to brag as lustily as [a] chanticleer in the morning, standing on his roost, if only to wake [his] neighbors up.” But I went to the woods to awaken in myself what I needed to live among my neighbors—to bring my own share of solitude, of inwardness, and faith in the invisible in others back into the daily world. That, it turned out, was the point of vanishing: to return.

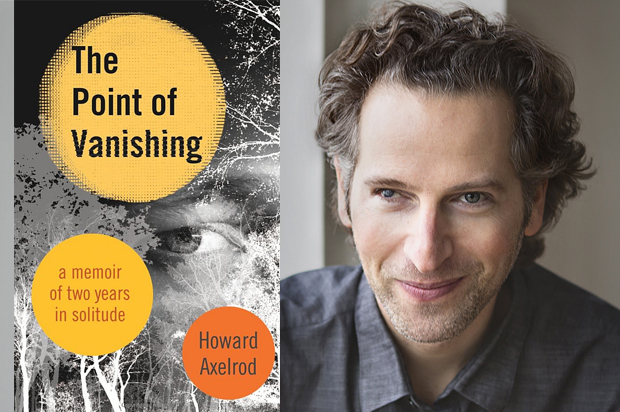

This is an adapted excerpt from “The Point of Vanishing: A Memoir of Two Years in Solitude” by Howard Axelrod (Beacon Press, 2015). Reprinted with permission from Beacon Press.