On Oct. 1, 1985, in an 11-room house on 40 acres of saltwater farm in the Maine town of North Brooklin, E.B. White died. In the latter days of his life, suffering from senile dementia, he’d occasionally charitably mistake his bedroom for a suite at the Algonquin. Out the door, down by the cove’s edge, his typewriter rested in the wooden boathouse where he wrote his most enduring works, including much of "Charlotte’s Web." He might have taken the boathouse for somewhere else, too, for at 10-by-15-feet it was the same size as Henry David Thoreau’s cabin off Walden pond.

This was not White’s design, though it may as well have been. “Every man, I think, reads one book in his life, and this one is mine,” he wrote of "Walden" in a 1953 New Yorker piece. “It is not the best book I ever encountered, perhaps, but it is for me the handiest.”

He first read the book as an undergraduate at Cornell, according to his biographer Scott Elledge. The copy he carried with him throughout his life is a small blue Oxford World’s Classics edition, purchased some time later in 1927. The copy that remains with his papers at Cornell is a brown and green edition from 1964 with an intro by White and a Duraflex cover, just in case the reader wishes to ramble off to the woods with it. But there were many others throughout his life, each encompassing a side to the avuncular essayist most readers didn’t see.

There was the "Walden" an anxious White read in college, the wisdom of which sustained him through the spectacular failure of his early working days (four jobs in seven months) and, in March 1922 when he was 22, launched him on an 18-month jaunt across the country with his friend Howard Cushman. The "Walden" a smitten and shy 28-year-old White gave to Rosanne Magdol, a 19-year-old secretary at the New Yorker, when she set off for a few months at a yoga camp. The elegant edition a 29-year-old White gave to Katharine Angell, at Christmas, the year before they married. The copy a 68-year-old White gave to his step-granddaughter, Caroline Angell, at Christmas 39 years later in 1967.

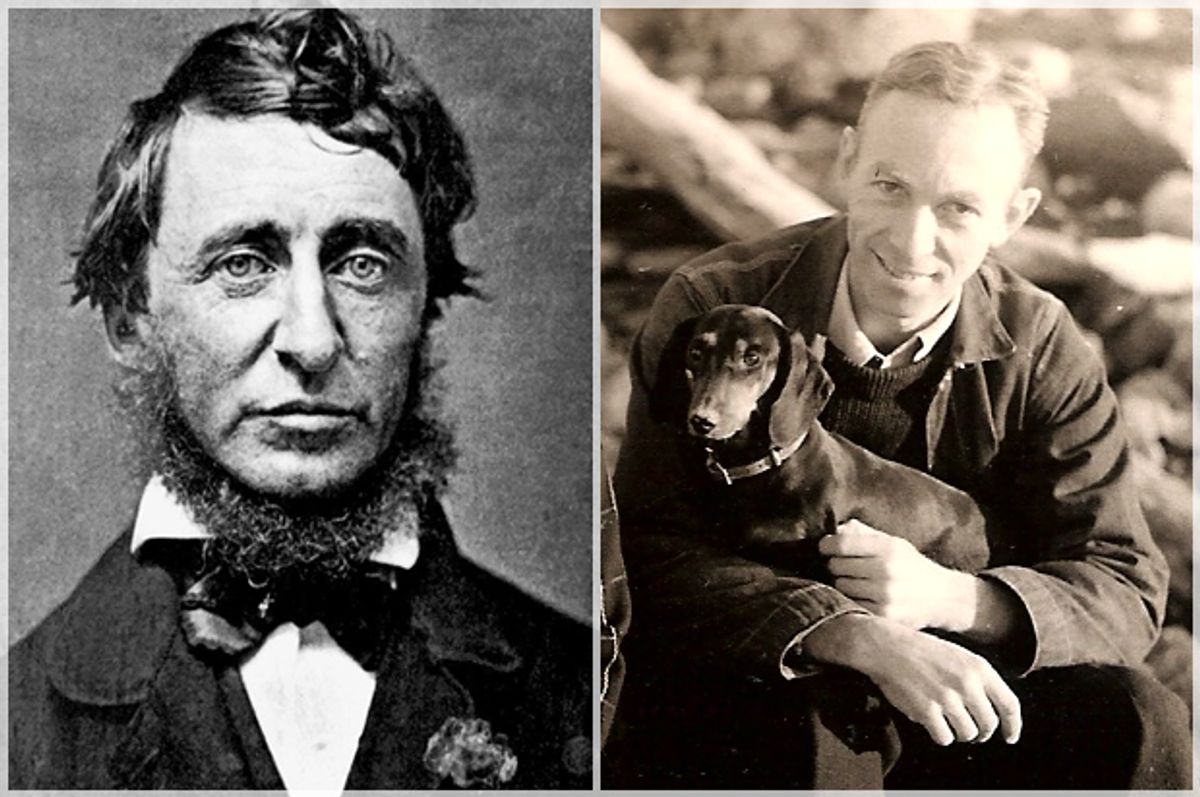

Throughout his life — in letters, three famous essays and an introduction to the work — White paid homage to and gently mocked Thoreau, a man who bravely isolated himself in a cabin walking distance from his mother’s house and mused on the absolute failures of his society.

“Thoreau’s assault on the Concord society of the mid-nineteenth century has the quality of a modern Western,” White wrote in the summer of 1954. “He rides into the subject at top speed, shooting in all directions.”

It’s an apt description. Thoreau sets "Walden’s" self-reliant tone in the original more or less immediately with his epigraph — a quote from his own book. It turns out he may be the only man worth quoting. The next 70 or so pages are a spectacular sequence of attacks and blustery principle. He suggests that slavery to one’s own false beliefs is worse than physical slavery (though he abhorred both sorts); he famously declaims, “the mass of men lead lives of quiet desperation”; he critiques all old people, writing, “I have lived some thirty years on this planet, and I have yet to hear the first syllable of valuable or even earnest advice from my seniors.” His vitriol transcends space and time, as made amply clear when he launches a fresh critique with a mutinous, “As for the Pyramids...” No one — reader nor pharaoh — is safe.

White found a humor in Thoreau that Thoreau didn’t quite see in himself. Like White, he was ill at ease in the working world, a fate that continued well past his time at the pond. A year before returning to civilized life on Sept. 6, 1847, the 29-year-old Thoreau was imprisoned for refusing to pay taxes on moral grounds. A mysterious friend—assumed to be his aunt—frustrated his protest and, to his chagrin, bailed him out. Thoreau turned the evening into an essay on civil disobedience. His friends had different conclusions. The next year, the storm clouds of self-reliance forming again, Thoreau deigned to pay only because, if he didn’t, his friends would.

“Thoreau is unique among writers,” White wrote, “in that those who admire him find him uncomfortable to live with … I would not swap him for a soberer or more reasonable friend even if I could.” A century on, he was still paying Thoreau’s taxes.

White found in Thoreau a moral compass — the emphasis on simplicity that defined both writers’ honest voice and intentions. Thoreau’s comical resistance to all standard careers gave White an ideological basis for setting out after the life he wanted to lead. From Thoreau’s dyspeptic and euphoric ramblings, he developed a sense that you shouldn’t take yourself too seriously, but should take life very seriously indeed.

“If our colleges and universities were alert,” he wrote on the hundredth anniversary of the book, “they would present a cheap pocket edition of the book to every senior upon graduating, along with his sheepskin, or instead of it.” As White grew older, worried youths would seek his advice, and he took up the suggestion himself.

“At seventeen, the future is apt to seem formidable, even depressing. You should see the pages of my journal circa 1916,” he wrote to one such young woman in September 1973. “You are right that a person’s real duty in life is to save his dream, but don’t worry about it and don’t let them scare you. Henry Thoreau, who wrote Walden, said, ‘I learned this at least by my experiment: that if one advances confidently in the direction of his dreams, and endeavors to live the life which he has imagined, he will meet with a success unexpected in common hours.’ The sentence, after more than a hundred years, is still alive. So, advance confidently.”

A few years before the end of his life, White wrote a new introduction to his now classic "One Man’s Meat." He had written the essays leading up to and during World War II when he moved his son and wife from their New York rental to their house in Maine. “Once in everyone’s life there is apt to be a period when he is fully awake, instead of half asleep. I think of those five years in Maine as the time when this happened to me.” More than a century earlier, on a pond 263 miles south on I-95, Thoreau felt the same. “To be awake,” he later wrote, “is to be alive.”

White was awake. But if Thoreau was the rooster shrieking at the top of his lungs, White was the brave mouse setting you straight. If less original a philosopher, he is a better friend to his readers than Thoreau, more tolerant of all save moral weakness and the failure to resist life’s invitation. This was the common theme for the two — the danger of the sort of forgetting to which every generation, with the not-so-new distractions of its new technologies, is prone. White never forgot Thoreau. White’s son Joel wrote the last of White’s anthologized letters on July 5, 1985. White was too sick to respond to his friend Charles G. Muller, who had sent him a short note on June 26 along with an article he thought his friend would like. It was called “The Man Who Found Walden Pond.”

If White didn’t read it, it’s just as well. He knew that every man is to find his own Walden Pond — that the good writer shows his or her readers the path to theirs. For this knowledge, he owed Thoreau a debt. Were they contemporaries, he would have paid it, for White is the sort of friend Thoreau could have used — laughing at him, encouraging him, and agreeing solemnly to keep in view what all living creatures are given, which to forget would be to make of life only a waiting for death.

Benjamin Naddaff-Hafrey is a writer covering media, tech, music and American history. Previously, he founded the music section at Mic. Follow him at @bhafrey or email him at bhafrey@gmail.com.

Shares