When James Andrew Miller and Tom Shales’ book “Live From New York: An Uncensored History of Saturday Night Live” came out in 2002, it was heralded as the definitive behind-the-scenes look at the legendary late-night institution. Containing interviews with hundreds of writers, cast members, hosts and NBC execs, spanning from the hedonistic heyday of the Not Ready for Primetime Players through the troubled “Saturday Night Dead” years into the new golden age of Ferrell and Fey, the book is a rich, densely-populated tribute to the show’s legacy and its enduring impact on entertainment, politics and American culture at large.

On Oct. 6, Miller and Shales are releasing the paperback version of the updated edition, with its 200 new pages covering the last 10 years of “SNL.” While the show has always gone through ups and downs, this past decade has been a particularly tumultuous one, as the show has fought to forge a path for itself in the rapidly changing digital world and to remain relevant in an increasingly competitive and fragmented viewing landscape.

In the new pages, we hear the show’s recent history described by the people who were there in the trenches: Andy Samberg discusses the rise of “SNL’s” now-omnipresent digital shorts; Tina Fey and Sarah Palin reflect on the political impression that defined the 2008 election; while Kenan Thompson, Sasheer Zamata and other cast members weigh in on the diversity casting crisis that engulfed the show last season.

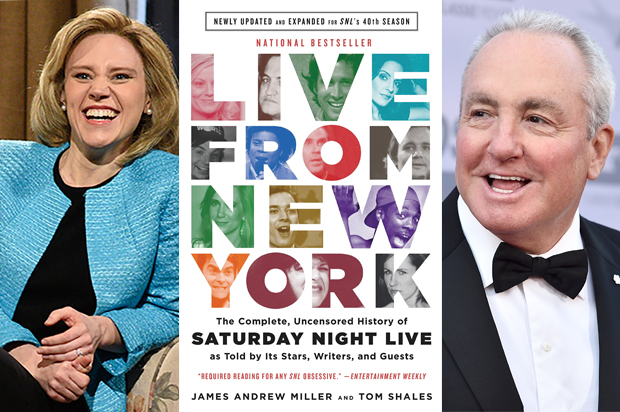

But, as ever, the most important figure is producer Lorne Michaels, the enigmatic visionary who reshaped the entire entertainment industry in his own image, and to whom the book serves as testament and tribute.

Ahead of the show’s 41st season premiere this Saturday, we sat down with Miller to talk about the show’s evolving history, its current challenges, and his hopes for the future of an American institution.

This interview has been lightly edited and condensed.

I was really impressed by how candid the cast members and writers were, and how open everyone was about their dislikes and their grudges. How did you get people to open up?

I don’t mean to be pretentious about this, but the goal is to make a book of record. In terms of how certain things really happened, you want it to be in that book. So I think that people understand that this is their chance to really speak the truth, and speak honestly about what they did and what they felt, and who was problematic.

Was there anyone who particularly surprised or impressed you during the interview process?

Well, it’s funny because you see these people on TV, and you always wonder going into an interview: Are they going to be like their persona on TV or not? Take somebody like Chris Rock, for instance, who’s incredibly funny – but he winds up being so smart too. I mean, the guy was so smart. I remember leaving that first interview with him and thinking: Whoa, yes, his stand-up is great, and he’s fun in the show, but there’s so much more going on.

There were some amazing anecdotes that came out, like when Bill Murray talks about carrying Gilda Radner around a party just before her death, the sort of amazing little moments that you were able to elicit.

When you hear something like that you just realize how special that is, how really incredible. At that moment, you almost stop being an interviewer and you’re just a fan of the show. Gilda, Belushi, Phil Hartman: These are people that you wish you could have interviewed. But it was so incredible to hear [Murray] talk about that moment, and to hear people talk about her. Because the truth is that there were other people that were part of “SNL,” and then people would say, “I couldn’t wait for him to leave” or “I couldn’t wait for her to leave.” So when somebody like Gilda comes along, you realize how deep-seated the love is.

When people in the book talk about it, it really does seem that there was sort of a magic happening in those legendary first five years of the show.

Absolutely. Look, there were a couple of things. One, it was new. So just the fact that it was new and it was breaking down so many barriers, and we’d never seen anything like that. And there was no expectation that it was going to work. I think Lorne understood it, but certainly a lot of the members of the cast didn’t. So there was just so much new about the first five years. And then the incredible talent, and the fact that they were, week after week, still messing around with convention, and being really disruptive in the most delicious way. So I think I totally understand when cast members after those first five years looked back with envy or intimidation. It was just inevitable given the weight and the import, the magnitude of those first five years.

Can “SNL” still do that sort of risky, ground-breaking comedy, given how long it has been around and all the new competition it faces?

I think it can still push boundaries. But the problem is that our world has changed, so some of the stuff that they do Jon Stewart was doing, and now John Oliver is doing, and Stephen Colbert was doing, so they’re not the only game in town. [These other shows] may not be doing sketch comedy, but just in terms of sensibilities and being really satirical about what’s going on, the landscape is a little cluttered, frankly.

Do you think that “SNL” can stay relevant in the current political landscape when pitted against John Oliver, and Colbert, and all those guys?

This is what I was trying to say at in my recent Vanity Fair piece. They’ve always had a special place and this year they need to keep that place. They need to not be conflated with other shows that are doing satirical, political humor. That means the sketches have to be very distinctive and noteworthy and the writing has to be as sharp as ever. I think it’s going to be an exciting year for them, because there’s a lot of material.

[Longtime writer] Jim Downey was a very prominent figure in the book, and he is pretty harsh when speaking about the show’s politics in recent years. He says that the show hasn’t done anything surprising in recent years and that “SNL” has become “an arm of the Hollywood Democratic establishment.”

The thing I love about Jim is that he’s so genuine. He doesn’t pander, and he’s just one of my favorite people to interview because you really get to understand how he feels.

The 40 years of “SNL” kind of run like an EKG. There are triumphant times, there are downtimes, and there are transition years. And I think that some of that is mirrored also in terms of political years. 2008 was incredible, with Tina playing Sarah Palin. But I think Jim was trying to say that they’d become a victim of their own success – boy, they don’t take as many chances as they used to. And I think that’s what he was really speaking to, and I think that kind of frustrated him.

Whereas Horatio Sanz, in the book, refers to Downey as “the Karl Rove of SNL,” and he expresses the concern that Lorne leans too much on Downey instead of relying on more liberal writers like Seth Meyers. And that the show hasn’t been tough enough on the GOP in recent years.

One of my favorite indoor sports is at a dinner party or when you’re just sitting around with friends, and people will say, “Oh, you know, ‘Saturday Night Live’ is a really a Democratic show.” And then somebody will say, “Oh no, no, no. Its a really conservative show. Jim Downey’s a really big conservative, and you should see the way he skewered Hillary.”

In a way, the show’s been incredibly successful in the sense that you don’t think it’s an arm of MSNBC or Fox News, or something like that. I think that they’re an equal opportunity offender. They like messing around with everybody who’s on the stage. And I think that’s really important because if there was a de facto branding of their political philosophies, that would be really detrimental.

Do you think that Lorne has become more afraid to go after the left, or to do humor without thinking about the political consequences?

Somebody once tweeted to me: “I just saw Lorne at a restaurant with the Clintons. And you have to write about this, because how can he make fun of them now if he’s hanging out with them socially?” And I wrote back, “You don’t know Lorne.” Lorne’s got a big world, and there’s lots of interesting, famous people in there, but that doesn’t necessarily mean that you’re out of bounds.

There has always been this debate about the extent to which “SNL” actually influences politics on the ground. There are people who say that because Will Ferrell’s Bush was so lovable, that it turned the tide of the 2000 election. And there’s also the viewpoint that Tina Fey’s Sarah Palin impression is really what ruined her. How strong do you think “SNL’s” political impact is, ultimately?

I’m not sure if there’s somebody who goes into a voting booth and votes a certain way because of an “SNL” sketch. But I will say this. The Will Ferrell-George Bush thing was really interesting for me because my Republican friends said, “I can’t believe how ‘SNL’ is killing Bush. They’re making him out to be this idiot, and he’s so stupid, and he’s under Cheney’s control.” And my Democratic friends were saying, “I can’t believe how ‘SNL’ is helping Bush, because at the end of the day, they make him out to be the kind of guy you’d like to go out and have a beer with.” And studies show that that’s partly how [people] calculate who they’re going to vote for.

So I don’t think it’s directly linked to how somebody votes, but I think there’s a kind of subconscious branding you have in the back of your mind. I think that there were things with Sarah Palin that may have been more deleterious to her than Tina, like the Katie Couric thing.

Let’s talk a bit about the coming election: In your recent Vanity Fair piece, you point out that the Donald Trump impression is quite difficult because he’s already such a larger-than-life character, and someone in the book described Obama as an impression with a “10.10” degree of difficulty.

I think the Trump thing is like, when the Lord wants to punish you, he answers your prayers. Because there’s this unbelievable character in the race, right? So just to jump into the writers’ room: Everybody is throwing out ideas like, “What if Trump says something about Carly Fiorina’s face. Y’know, ’look at that face! You can’t be president with that face!’” And someone else will say, “No, he actually said that!” Or “What if he gets on a riff about John McCain, and just says like, ‘I don’t even think he’s a hero.’” “No, no, he already said that.” So it’s like, where do you get stuff? It’s a little tricky.

And Jay Pharaoh is back doing Obama. Can you talk a little about the notoriously difficult Obama impression?

This has been the case since 2007. Obama is, without a doubt, the most difficult president in the history of “Saturday Night Live,” in part because he doesn’t have tics. He doesn’t have — Jim Downey calls them ‘handles’ — almost like this port of entry where you get in there and mess around with his mind or his affectations.

One of the great defining sketches of the Bill Clinton era was Phil Hartman jogging and he makes a campaign stop at a McDonald’s. He’s talking to everybody about policy and he says, “Hey, can I have a bit of your burger? Can I have a sip of your shake?” You saw that Clinton boyish id there and it was just perfect. Obama doesn’t have something like that. It’s much harder for him.

In the update of the book, you write a lot about the new digital culture surrounding “SNL” — how everything gets picked up and dissected online nowadays. It seemed that a lot of the cast had trouble with the level of backlash they face online on a daily basis. In your experience, is the Internet making it harder for “SNL” to do its job?

There’s a great positive, which is that “SNL” doesn’t need to have people watch it on Saturday night at 11:30, like you used to, in order to appreciate it or see it. The next morning, you can get basically every single sketch online. The bad news is now there are really weird metrics attached to it. Before, the show would get a general rating. Now — Andy Samberg and Jorma and Akiva [from “The Lonely Island”] talk about this — like: Oh my gosh, look at the hits on “Lazy Sunday.” And you can do that with sketches, too. Like, the question of how viral does a sketch go?

Right, they’re already competing to get airtime. Then they’re competing to be aggregated on Twitter.

This is stuff that 90 percent of the earlier cast never even imagined they had to deal with. I can’t tell you how many cast members said “I had to stop Googling myself. I stopped looking at whether or not a sketch was picked up by Deadline or HuffPo or Slate or Salon.”

“SNL” has been criticized a lot for its lack of diversity, and you cover that a lot in the book, including the casting call for black female cast members that took place last year. What was the mood like from the staff around this issue? It seemed like there was a split of opinions.

Clearly, there were people who were bothered by it. When that whole controversy started up, I know some people were surprised by the extent of the conversation and how much it became a national conversation. I think it was just one of those reminders that “SNL” is a pretty big blip on our cultural radar. It wasn’t an insignificant conversation or controversy or debate.

That said, Sasheer [Zamata] is just amazing and I think she’s been a terrific addition to the cast. She’s incredibly talented. There’s no one in the world who could say — or if they do feel that way, have them call me — that she doesn’t belong in that cast. I also think they were really smart about how they brought her along, the first night. She is very methodical about how involved she got. It was really smart. And so that’s behind them now.

A number of female writers and cast members you interview — Nora Dunn, Janeane Garofalo — talk about the historical notion that “SNL” is bad for women. How has that changed over the years, and do you think the assessment of “SNL” as a boys’ club is a fair one, or has it been overblown?

When someone says that they feel something about their workplace, I try never to sit and judge and say, “Oh wow, that’s overblown.” I’m not a woman, I wasn’t in the room when a guy may have been somewhat demeaning. I can’t say. What I do know is that your question is rooted in truth, which is that a lot of people felt the way that they did. And I think that you can’t be on the air for 40 years and not go through changes. I think that Lorne is not the type of person to understand a problem of that magnitude and then ignore it. I will say this, that from the time Tina [Fey] became head writer, I did not hear that once from anyone, about Tina. Not once.

Julia Louis-Dreyfus has a nice segment in the book where she talks about going back to host in 2006, and observing this newfound sense of camaraderie on staff, which she credits to the women on the show at the time, like Amy, Tina and Maya, and how they really changed the attitude there.

Maya was terrific on this subject. When Maya talks about the sisterhood that exists in the “SNL” biosphere, it’s actually beautiful. She’s so freaking articulate. It’s crazy. I could have done 40 pages just on her.

I think I’ve interviewed 570 people for “SNL,” and Julia Louis-Dreyfus is on my Mount Rushmore. She was part of the earlier days and she was really candid about that. And I was so glad to interview her now for the new volume because she did come back and host and she’s just so unbelievably smart and has this keen sense. Her radar is amazing.

Who else is on your Mount Rushmore?

Maya. She doesn’t have the visibility that Tina and Amy have. It’s easy to love Tina and Amy, because we know them so well and they are smart, they are gracious. When I interviewed Amy, she was in the middle of production and even though her reps said she had limited time, she was like, “Do you need anything more? What else can I help you with?” That’s a window into somebody’s character.

One of the reasons why I felt that this had to be an oral history was because each of these people have such distinct sensibilities and they’re really interesting to listen to. There’s no way — I don’t care if you’re Hemingway — you can write prose that will capture the uniqueness of all of them. There were days when I would have four unbelievable conversations. I mean, they’re really, really smart and they’re candid and they really care. I know “really care” sounds like a saccharine phrase, but here’s the thing — and Kristen Wiig was so great about this — you don’t sleep and you don’t see daylight and it’s not really glamorous. But they’re committed.

When you’re on “SNL,” you’re swimming in the deep end of the pool. You cannot fake it. If you fake it, then Lorne and the writers and the rest of the cast will see it and then on Saturday night, the audience will see it. There’s just no margin for error. You gotta come through. So, it requires a lot of commitment. I actually had many of the cast members talk about the fact that their work life was much more demanding on “SNL” than it was on a TV show or a movie, and I think that says a lot.

Lorne is this really fascinating, almost mythical figure who seems to inspire fear and love in equal measure. People describe him as a father figure, a mentor, Obi-Wan Kenobi, all sorts of things. How would you characterize Lorne’s relationship with his cast and how that has changed over the years?

The thing I really appreciate about Lorne is, in some ways, as much as he didn’t like old Hollywood and how he’s been a chief architect of a new era, he’s a throwback. He’s iconic, like Louis B. Mayer, Samuel Goldwyn and Irving Thalberg. When you say Lorne, it’s like Cher. The least-used word in the world is Michaels, because you don’t need to say it.

I think the fact that he’s been doing it for 40 years is obviously noteworthy, but more importantly he has a very complex relationship with staff and with writers. And I think what’s been interesting to document under the rubric of cultural anthropology is Lorne’s growth through the years and how it has manifest with the staff. Because person after person [has said] he has been, particularly since having children, much more benevolent. He’s been a little less mysterious.

The first twenty years of the show, people were absolutely terrified of him. Not everyone, but there was no doubt that he was the head raccoon. And people always were trying to figure out “is he mad at me, does he love me, does he like me?” And I think that nowadays there’s less anxiety about that. He’s much more of a father figure. He’s much more involved. Cast member after cast member talked about how he’s great with career guidance and he’s been a real mentor. That’s been really interesting to write about.

And now Lorne doesn’t just have “SNL,” he also has “The Tonight Show” and “Late Night,” and he recently had “30 Rock.” NBC late nights are entirely his domain. Has that changed the dynamic on the show at all?

If I were to say to you, Lorne Michaels has “30 Rock,” an Emmy-winning primetime show, he’s got late night shows — I’m conflating eras here — and he’s got “Saturday Night Live,” one might think, okay, he’s been doing “SNL” a long time, he’s kind of on autopilot, he’s going to devote his energies to “30 Rock” and launching Jimmy Fallon and someone else is going to be the de-facto head of “SNL.” And you’d be totally wrong. Because “SNL” is still the center of his universe. He’s never missed a show. Never. So in terms of the hierarchy of needs, I’m sure Jimmy Fallon and Seth and Tina, when they needed him, that’s fine. But he has always been wedded to the fact that on those 20 [“SNL”] shows a season he’s going to do everything he can that week to make it the best show possible. And that’s pretty extraordinary.

You referred to “SNL’s” trajectory as being like an EKG machine. What are we in now, a peak or a valley?

Last year there was a lot of attention because of the 40th anniversary and the special itself was so spectacular. It was kind of like a tsunami that washed over individual episodes. I do think last year and the year before, one of the things we saw is that the show has the tendency to be a little host-dependent. So what’s happening from a ratings perspective is people aren’t sitting down because it’s Saturday at 11:30, they’re saying “Oh, Justin Timberlake is on, let’s watch that.” So that puts a lot of pressure on the booking department in the sense that you’ve got to make sure the hosts are a certain caliber.

I think one of the things the political year may do for “SNL” is that people will not pay so much attention to who the host is and they’ll want to just come and see all this great political humor.

I was excited when I heard Taran Killam was going to play Trump, because I think he’s such a huge talent. Is there anyone that you are particularly excited about on the show right now?

I would watch Kate McKinnon read the Yellow Pages. She’s out of this world, crazy talented. Unbelievable. And I think Aidy [Bryant] has grown so much. But in terms of the political stuff, Kate is doing Hillary this year. And she’s off-the-charts talented.

Other than Kate McKinnon, which cast members do you hold a soft spot for?

I’m really glad Kenan came back; there was a rumor he was going to leave. And that would have been sad. I understand everybody has their own shelf life at “SNL” but I’m really glad he’s back. There’s a bunch of really talented people. I’m always going to root for “SNL.” Not just because of its great history, but because I think it occupies a really special and important place in the culture and in television. Wherever I give a speech or a book signing, people say “Oh god, ‘SNL,’ it used to be so great.” Come on. It’s such a lazy way of looking at things.

A lot of these people haven’t even seen the show in four or five years. So I’m rooting for it. I know it’s cooler to be cynical, but I’m kind of burnt out on cynicism. I tell my kids, I think we live in a world where good news travels too slow. So I’m happy to say I’m rooting for it. I hope they have a great year.