It was 50 years ago, in 1965, in Mademoiselle magazine, of all places, that Susan Sontag announced the existence of a “New Sensibility” afoot in American culture. By 1966, that phrase would reach a more intellectual audience with publication of her path-breaking collection of essays, "Against Interpretation."

Sontag, however, was not the only figure in 1965 to flip that phrase around. Tom Wolfe, in the introduction to his best-selling book "The Kandy-Kolored Tangerine-Flake Streamline Baby," had exclaimed: “The hell with Mondrian, whoever the hell he is ... Yah! lower orders. The new sensibility – Baby baby baby where did our love go? – the new world, submerged so long, invisible, and now arising.”

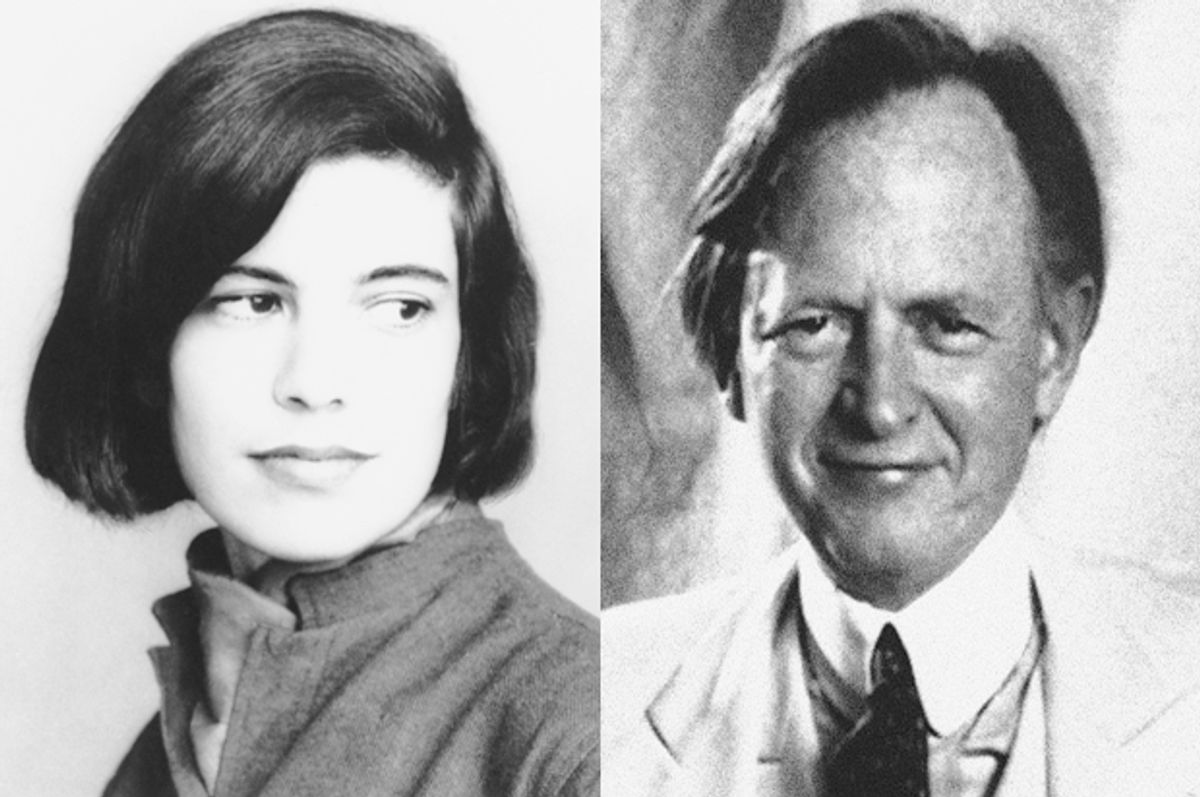

Wolfe and Sontag jointly staking out the territory of this new sensibility? Could a more unlikely pair be imagined? Wolfe was the newspaperman given to wearing a white suit, white spats and fedora; he was smart and cynical but capable of enthusiasm, especially if it went against the grain of the mavens of elite culture. His prose hit like a howitzer, full of capital letters and exclamation points. In contrast, Sontag was the emerging “dark lady” of American letters, decked out in black turtleneck and a torrent of dark hair. She was tall and commanding; there seemed to be nothing that she had not read. Her sentences, if not quite sensuous, were beguiling, full and subtle, with a fine eye for aphorism.

Which of the pair first came up with the phrase "the New Sensibility"? Probably Sontag, because Wolfe may have been slyly poking fun at Sontag when he quoted the words “Baby baby baby where did our love go?” They were from the song “Where Did Our Love Go?,” by the Motown Group the Supremes. It had been a No. 1 hit on the pop charts in August 1964. What’s the connection?

Although Wolfe might have appreciated the tune’s contemporary rhythm and energy, the group singing it had been singled out by Sontag in her own article on the New Sensibility. While Sontag’s roots were sunk deep in European modernism – and its most recent offshoots – she argued that elite American culture lacked a danceable beat. Why must everything be so heavy and brooding? Why must intellectuals crawl over every cultural expression like ants upon potato salad at a picnic? She famously announced that intellectuals and American culture needed to be liberated, to begin to enjoy the “sensuous surface of art without mucking about in it.” In sum, she finished the opening essay of her book with the words: “In place of a hermeneutics we need an erotics of art.”

In 1965, The Supremes were on her mind and record turntable. In a diary entry for November, she admitted to herself, “My biggest pleasure the last two years has come from pop music (The Beatles, Dionne Warwick, the Supremes).” In her book "Against Interpretation," in the essay “One Culture and the New Sensibility,” the Supremes popped up anew. What was wrong with intellectuals, such as Sontag, kicking off their shoes and dancing to such lively music? The edifice of high modernism would not tremble or tumble too badly. Maybe some of its imposing doors might even come ajar.

Indeed, as the essays in "Against Interpretation" indicated, the saturnine spirit of serious art existed nicely alongside the rhythms of the Supremes. Sontag, as a critic, craved both high and low art. But the films and plays, literature and art that attracted her were not quite popular. She was drawn to works that interrogated madness, bewitched with silence. She adored foreign films, cast in the Nouvelle Vague manner, that were often resistant to understanding, self-referential and anchored in the history of the medium. Her taste in fiction (present in her own novel "The Benefactor") was for prose without metaphor, a flat narrative voice, plots that were more dreamlike than logical.

Wolfe’s admiration was for quite a different world of culture, one that Sontag had never experienced – nor sought out. While they might both dig rock 'n' roll, he wanted a culture of energy, bright lights and ha cha cha. He loved the garish and outsized, hence his attraction to Las Vegas. It had “The wheeps, beeps, freeps, electronic lulus, Boomerang Modern and Flash Gordon sunbursts.” Hardly the type of expression associated with some of Sontag’s heroes, such as Samuel Beckett or Simone Weil. Wolfe traveled the United States in search of grass-roots cultural expression. He found it in the unlikeliest of venues, at least as he presumed for a typical New York intellectual. He wrote knowingly, and sympathetically, about Junior Johnson, a race-car driver, “a modern hero.” He marveled at the craftsmanship and culture of auto detailers. He readily stooped to consider the instant celebrity of one Baby Jane Holzer, whose key attribute was tonsorial: “Her hair rises up from her head in a huge hairy corona, a huge tan mane around a narrow face . . . all that hair flowing down over a coat made of ... zebra!”

No black turtlenecks for Tom Wolfe.

The tastes of Sontag and Wolfe, in that magical year of 1965, rarely overlapped. But each of them was open to a new sensibility that was open to extremes – to pushing things, willing to go too far, ready to offend by over-expression (think here of folks gallivanting around onstage, scantily clad, engaged in some ritual with pieces of meat and fish, as in Carolee Schneemann’s performance piece “Meat Joy,” or Andy Warhol statically filming a friend sleeping, hour after hour). Such strange, shocking performances were popping up everywhere, also found in the confrontational theatrical experimentation of the Living Theatre, the performative work of Yoko Ono, the creative egoism of Norman Mailer, and the intense fascination in art with madness, breaking boundaries and violence. (Think here of the aesthetics of the bullet-ridden scene in "Bonnie and Clyde.")

Sontag and Wolfe named but did not create the culture that was suddenly swirling about them in the mid-1960s. Its roots could be found easily in the work of John Cage, who during a magical summer in 1952, not only debuted his piece of radical composing, "4’33”," with its silence allowing new sounds to be heard, but also orchestrated at Black Mountain College the first happening, a chaotic event that combined poetry reading, snake-dancing, artwork, music and more, all occurring at the same moment. The excesses, the cultural liberation that Sontag and Wolfe were celebrating existed throughout the 1960s, although it ran up frequently against censorship laws (which were slowly but surely losing the campaign) and conservative notions of what constituted art. But the new sensibility, in everything but name, was emerging in the 1950s, in the poetry of Allen Ginsberg, the photography of Robert Frank, the amoral novels of Patricia Highsmith, the smoldering and ambiguous sexuality of Brando, the artistic mingling of forms and methods in the art of Robert Rauschenberg, and in early sexual energy of rock 'n' roll. It had simply blossomed by the mid-1960s, hardly needing the British invasion of the Beatles and other groups to strike the chords of cultural freedom and fun.

For Sontag, the New Sensibility was a battering ram against academic stodginess and purity. While this drew her to Camp culture (she had first hit the headlines with an essay about this phenomenon in 1964), she did not throw the baby out with the bathwater. She wanted all that culture had to offer, however outrageous. Hence, she wrote with uncharacteristic enthusiasm about the film "Flaming Creatures," with its blurred scenes of nude performers and transvestites in motion – and no discernible plot or raison d’être. But, as she had made clear in her “Notes on Camp,” Sontag was both “drawn” to Camp -- and “offended by it.” Wolfe invariably opted, at least in print, for the outrageous, especially when it allowed him further opportunity to poke fun at the self-inflated egos and pretensions of cultural worthies. Whether he identified with the old or new culture remained unclear, hidden behind his inscrutable smile.

Looking back 30 years later, Sontag admitted that her enthusiasm for the excesses of the New Sensibility had a strong element of the “evangelical zeal” of a recent convert. Yet, she remained adamant that the tired distinction between high and low culture needed to be cast aside. She had put her finger on the pulse of the emerging sensibility.

The New Sensibility, now 50 years after being labeled by Sontag and Wolfe, remains our cultural configuration. We live is a culture of excess. Divisions between high and low have been largely obliterated, limitations on violence erased, and distance between performer and audience crossed, the division between the mad and sane broached. Sontag had worried in the 1960s that once an analyst applied a name to a phenomenon such as Camp, that entity was in danger of being contained, somehow crushed of energy. Such has hardly been the case for the New Sensibility. The distance from "Flaming Creatures" and the celebrity culture of Baby Jane Holzer to Kim Kardashian and the twerking of Miley Cyrus seem more of a piece than of a different entity entirely.

George Cotkin is Emeritus Professor of History, California Polytechnic University, and author of the forthcoming book "Feast of Excess: A Cultural History of the New Sensibility" (Oxford University Press).

Shares