Over the past two decades, the phenomenon of climate denial has come into focus almost as much as climate change itself. We've now reached the point where the Republican Party is virtually the only conservative party in the world that's still playing ostrich when it comes to climate change. But is denialism alone enough to explain the psychological resistance to saving the planet?

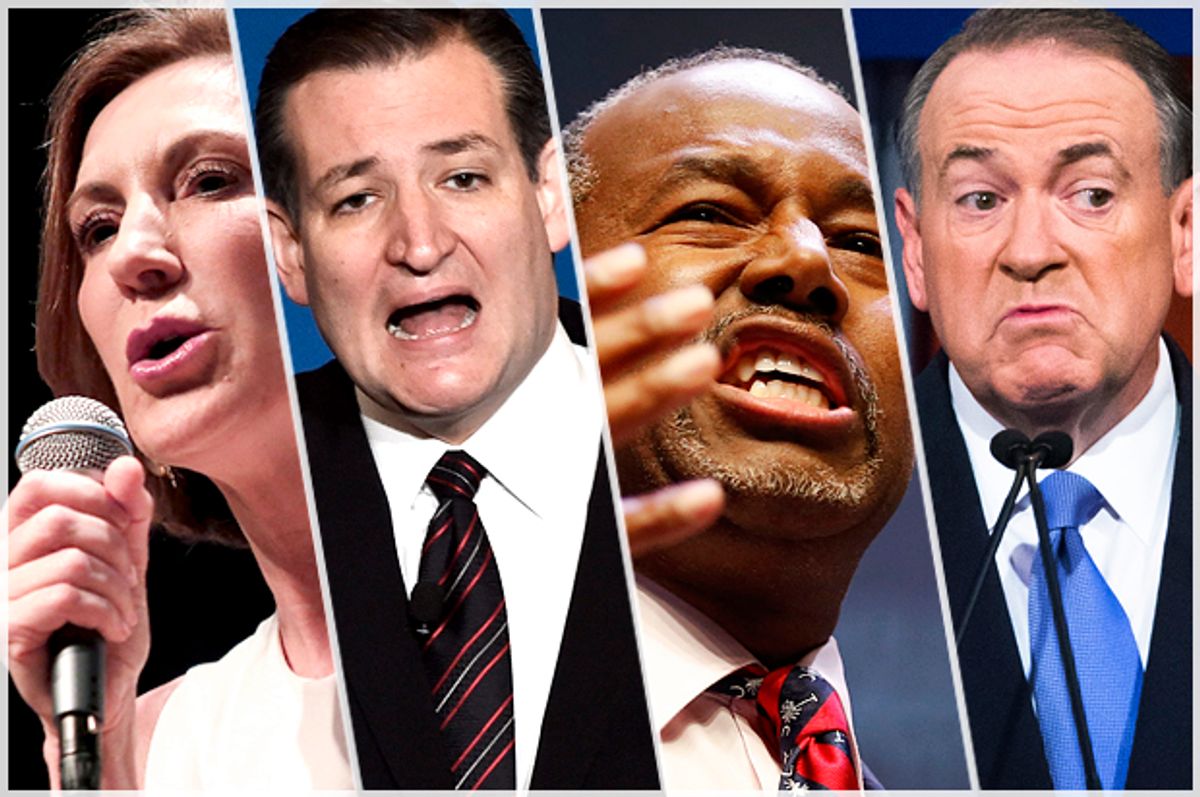

Canadian psychologist Robert Gifford, of the University of Victoria, doesn't think so. In fact, he's identified so many psychological barriers to action—what he calls “dragons of inaction”—that he's organized them into seven main categories, or, if each dragon represents a “species,” seven “genera” encompassing more than thirty separate “species” of dragons. In the current election cycle, even GOP presidential candidates seem to be drifting away from outright denialism, though still refusing to endorse doing anything. So the time may really be ripe for gaining a better understanding of the broader range of barriers out there (some of which may be getting more attention in the months and years to come) and what we can do about them.

Salon spoke with Gifford to explore this broader landscape. The transcript has been edited for clarity and space.

So, people are very familiar with climate denial. Thanks to Oprah Winfrey, people are very familiar with the concept of denial, and we know that there's been a lot of effort put into creating denial in the political realm. But you're taking a much broader view of the psychological barriers to doing something about climate change, both in people's everyday lives, and in terms of political action, from the local to the global level.

I wanted to start off by asking you a few basic questions: Where does this wider framework come from? How would you describe it as a whole? And what does it tell us? So those are the questions I'd like to start off with, if we could take them one by one, first, where does this broader framework come from?

It depends how far you go back. Basically I am a collector of things. I collect posters from the 60s, I collect baseball cards, I collect other stuff. So it started with people like yourself saying “Why is it that there's people out there who say they're in favor of the environment, but they're just not doing that much about it?” I've done a lot of interviews and a lot of journalists, especially broadcast journalists, want a kind of 30-second sound bite as the answer to that question. So I would look around and say, “Well, here's one reason.” “Well, here's another one.” “Here's another one.” Pretty soon I was basically making a list—another collection—of reasons or justification, or excuses about why people don't transit their good intentions into actual actions.

Once you started down that road, are very anything other things would point to as having helped to inform you shape your direction?

Yes, two things happened. I began to give talks to academics about this, and then somebody would raise their hand in the back row and say, “Yes, but what about this?” “What about that?” And most time I would say, “Yeah, you're right, that's another idea.” So at one point there were seven such dragons, then there were 12 dragons, then it was 18 dragons, and there got to be more, until there was like 22 dragons. My partner said, “Twenty-two is not a very sexy number. I think you better start organizing a bit, and find a sexier number than 22.” So now there are seven categories, and seven is a pretty sexy number. They more or less fit into these seven categories fairly reasonably. And so, seven is better than 22 or 28 or 33 or 34 wherever we are right now. That's how it happened.

The second part of it was, back in 2007 or 2008 the American Psychological Association formed a task force on climate change, so that official psychology could say something about its position. I was the only Canadian asked to be on this panel. So we had to start thinking more formally about all this, and so there was a special issue of American Psychologist, which is the house organ of APA, we wrote articles for the special issue, and that was the first time that the dragons found a formal home, was in the 2011 special issue of American Psychologist, and it actually turned out to be the most cited article in that special issue. [Copy here.]

So how would you describe the framework as a whole?

The attempt is—and who knows what baby dragons might be born or hatched or whatever they do, from here on out—the goal is to create a comprehensive periodic table, like in chemistry, of all the justifications and reasons that people offer. And now, pretty much, when I give a talk and somebody says, “Yes, but my cousin says this,” I'm almost all the time able to translate that to one of the existing dragons, even if the words might be a bit different. So I think in terms of the seven genera, or 33 species, it's pretty hard for people come up with one that doesn't exist. So I think it's kind of like in chemistry the periodic table, where the first hundred elements or whatever, after that, it's getting really really hard, you have to have fancy ways to add a new one to the chemical periodic table.

What does this approach tell us? What kind of information does it give us?

Besides being a near complete list better characterization of the justifications, obstacle psychological barriers, whatever words you want to call it, besides that it opens the door to the phase I'm into now, which is self-diagnosis. So okay, why is it that you want to fly to Costa Rica to see the rain forest, when you know that flying down there is not such a good thing? So, check off which of these 33 reasons are you using to convince yourself that it's okay. And then, once you start, assuming you're making an honest effort, doing that, then you can begin to do something about it. So, it's like identifying, more specifically, what are the problems, and it's easier to attack those problems than having them be, for you, unclear, or ambiguous, or totally unknown.

What about feeding into organized social efforts to change policy or develop policies that people will adopt and buy into?

I'm not a political scientist, or policy person per se, but it seems to me that what somebody who works for a government agency of any kind, from the municipal level up to the federal level could do, is begin to, you know, greatest good for the greatest number, sort of John Stuart Mill a bit sideways, and say, which of these justifications is most often used by most people, for which of the heavy carbon actions—whether it's diet, or transportation, or home heating or whatever. And then we can formulate a policy which could include incentives, which I prefer to penalties, that deals with those as opposed to—and this has happened—lots of time, money and effort being spent on programs and policies that either are simply not going to change, because there to hardwired into the public DNA, or simply miss the target like shooting at a target and missing it, because it's wrong policy for the wrong behavior. So I think the dragons form the basis for the possibility of better targeting public funds and efforts—and it doesn't have to be government, [it could be] networks, social networks, among people who are trying to do this—so basically overall it's a way, the efficiency expert's way of the looking at things, so that the effort and time that we have to spend, which is always limited, is better targeted.

Okay I like to go through the seven genera with you, go through them one by one, talk about a couple of the dragons each category to illustrate what they're about. Let's start with limited cognition.

This is probably the most numerous genera terms of species. It includes something that we don't have much control over, that we have limited control over, the ancient brain. According to physiologists, the physical aspect of our brains hasn't changed much for 30,000 years. What we were doing back then was wandering around the savanna, those of us with African heritage, as opposed to the 5% who have a Neanderthal heritage, we're wandering around the savanna, mainly interested in the here and now, because that's all that counted for survival. And here and now for climate change doesn't work very well, because it's a more global thing, that's going to develop over time. So we're certainly able to think about other countries other places, the future, but it's doesn't come naturally, we're generally by default focused on the here and now.

There's ignorance, there's having heard the message too often, there's some uncertainty, there's optimism bias which is, certainly optimism is a good thing but optimism bias, when it's faulty optimism is not such a good thing, there's problems with feeling that one doesn't have much control, the voters or voting problem. So there's a lot of these limited cognition issues that mean we don't spend enough time and effort thinking about the problem.

Is there anything you can say about how we can begin overcoming them? You do say that it dragons can be slain so what was promising and way of combating them in that genera?

The biggest thing, I call it “making climate here and now.” So when people think it's polar bears, or they think it's in the Sahara, or they think it's the future. It's almost everywhere now, there is some sign of it, so when people see that it's in their backyard, and they see that it's now they're more open to change, because it's the ancient brain, it's here and now, instead of off with the polar bears or the Sahara. So, that's the job of messengers, is to show everybody wherever they live the signs of it happening now.

Well, living in California that's been pretty easy to do this summer.

Yes, there's 750 people, 750 houses, plus all the associated buildings [burned in Northern California wildfires], it's crazy. Yeah, those people are seeing it. Yes, I grew up in California, in the cultural armpit of California, sometimes known as Sacramento.

Okay, so on to the next genera of dragons, then: ideology. What you have to say about that those?

Ideologies are problem because they're very broad umbrellas of ideas and all fit together, like a puzzle it's been assembled, you know a jigsaw puzzle has been assembled into a big picture. And so usually it covers lot more territory than climate change, climate change is one of the pieces of the puzzle. And so the difficulty with the ideology is that if the rest of the ideology fits climate change in a skeptical or denialist way, then it's very hard, because it's like taking trying to move the whole puzzle around. Between you and me I've never used this analogy before, but it seems to fit, but the obvious one is generally conservative politics. It's hard, but not impossible, to move that one puzzle piece with the rest of, you know, big business—“business is good,” “more and more,” “grow or die capitalism,” etc., it's hard to square that– that's not the right word with a puzzle piece–it's hard to fit that in with climate change. Although, I have to say that recently I've read some pieces that the real change some people think, is going to come when top business leaders see that it's actually going to hurt their business. And apparently there is a fair amount of movement among big business CEOs to say, “Yeah, it doesn't fit with my traditional views, but I'm convinced that this going to have a negative impact on my shareholders, and my shares.” So this is a bit strange, and a bit new, but this is great, because those people do have a lot of power. So that's one,

System justification is more about the average middle-class person, who says, “Well, does this mean my lifestyle is going to change? I don't really want to do anything because I don't want this boat to rock, I got two cars in the driveway, and a nice house here in the suburbs, I don't really want that to change.”

And then you have people who were kind of engineer-oriented, I know a lot of engineers who are on board, but some engineers, or some people who think engineers can solve every problem, have a techno-salvation problem, and in my view and think, well, it's not my job to do anything, the engineers will fix it.

Okay, then the next category the next genera of dragons is “comparisons with others.”

Yes, other people. For all of us, the people around us, our significant others, either that we admire at a distance, virtually on TV, or the people who are right in our lives, have probably more influence on us than we would like to admit. We want to think we're kind of independent, especially in the States – an individualistic society as opposed to a collective society – but even in the individualist society, and especially in the collectivist societies, what other people around us think or say or do is particularly important, both in terms of, “I feel like I need to dress like, act like, think like these people,” or in terms of comparison of equities—so “If she's not going to do it, if they're not going to do it, if that country's not going to do it, then why should we do it?” is the equity part.

So, broadly speaking, as much as we may not want to admit it, the other people around us are very important, and if they—it can work both ways, as I think I've said before—it can work negatively, if they're all telling us we don't need to, can't, or the other people ought to do something about it instead of us, and it can work positively, if we can create networks of families and organizations and cultures that are on board with the idea that we need to mitigate much more than we are now, then other people can be a positive as well.

The next category, or genera, was sunk costs...

Well, actually that category is called investment. Sunk costs are the financial side. Investments includes finance is, but it also includes other things, so it's not only financial. But sunk costs is buying a car, and then being told that you should take public transportation—it doesn't make sense. Or having resource stocks, and then be being told that you should be against resource stocks. So that creates what traditionally psychologists have called cognitive dissonance, or tension between what we think, and what we do. Smoking was a big one, a classic: it's not good for you but I do it, so what do I do? I either stop smoking or stop thinking it's bad for me. For sunk costs we have to either divest, get rid of the car, or just have an old clunker when we need it, and get on board, or it's hard to do both.

Sunk costs is just one thing. Habit, behavioral momentum is what I call it, is difficult to change. We've got jobs to do, we've got children to look after, grandchildren to look after, our health, whatever. So we tend to just keep doing today what we did yesterday, and a lot of his actions are not mitigative in nature.

Then, as I was hinting about with health, we have a lot of other things to worry about, health, being fit, making money, having a better house, lots of other goals that are legitimate, giving money to charity, so climate isn't always at the top of this list, or maybe even sometimes even close to the top, so sometimes it doesn't get the attention it deserves. We don't translate our intention into behavior, because we have these other things that we want to do, and that's a hard one because we do we all do have conflicting goals and aspirations, which is that one. So, those are the main investments: financial, habit, and other goals.

Let's move onto the next genera of dragons. Discredence is what you called it.

Yes, I'm happy with this word, I discovered it in some obscure place., I mean it's pretty obvious if you know something about English, the root is trust, with credence. So, this is just not trusting scientists, not trusting the government, as a kind of a cover for not doing anything. Or deciding that some program the government offers, is misplaced money or misspent effort, which it can be of course sometimes, of course. And then you have reactants, which is the kind of two-year-old mentality: “You can't make me do it,” “I'm a free person,” “I can kill people with his gun up I want to” -- joking, but not totally, as we've seen daily.

So, the next genera is perceived risks.

I teach consumer psychology sometimes. I always, of course, give it a very green spin, as opposed to how some people might teach it. One of the principles of consumer psychology has to do with—if you want to bring something new product to market, or get people to change—that people find the change risky. Should I go from this brand of razor blade to this one? Or this that fast food to the other one? So they list off these six kinds of risk, and when I was lecturing about it, I said, “Oh? Hey, those also apply to climate change!” Because people in general—except for the few people who fly off of cliffs with wings and kill themselves—most people are risk-averse. There's a lot of evidence that most people are risk-averse.

So there's functional risk, is this electric car going to work? There's physical risk, of riding bikes, I broke my arm a couple times riding bike. Financial risk, in putting solar panels up, will it pay for itself? Social risk, are people going to make fun of me? Psychological risk, are people actually going to bully me if I'm really different? Temporal risk is one about if I spent a lot of time researching this change, is to be worth the time? So all these really mean that people hesitate. Yes, I intend to put solar panels on the roof, but the financial side, but the temporal side, but the functional side. Are they get a fall off? Are they going to break? So I hesitate. So risk about hesitation. It puts break on the intention, and that's the whole idea of this basic category, this genera of dragons. It puts a damper on intentions.

Okay, so then the last one, the last genera of dragons you had was limited behavior.

Limited behavior is about not doing enough, and then saying, “I've done enough.” So, tokenism is “I recycled, therefore I'm done.” Or some small behavior which nobody is going to condemn, especially me, but to say that I've done my part when it's not enough in terms of... we need find way to get people to do a bit more in terms of what they think is enough.

The Jevons Paradox, or the rebound effect is an interesting one, because that's about being virtuous, in say recycling, and then saying, “Well, that gives me permission to do this other stuff,” which may be worse than the recycling was [helpful]. I throw out my old desktop, and that gives me the permission to buy three laptops, or whatever. Or it's like in the gym, I spent the hour the gym, so I can drink three beers. Or the one I like to say in my talk is “I bought a Prius, honey, let's drive to New York!” And there's actually evidence for that one. A guy in Japan found that people who bought fuel-efficient cars did drive more than people who bought fuel-inefficient cars, the year after they bought the car. So the rebound effect of the real thing, and it's psychologically like, you want to reward yourself for doing the right thing, but if that means spending more carbon than you did before, there's a net loss there.

Looking at all these things, all seven genera of dragons as a whole, what are other people able to do this with this? You mentioned some of this before you went through the list, but now that you've laid the list out, can you look back and cite anything more specific that activists, organizers, politicians or policymakers can take advantage of?

The big thing I think is the social factor, and that is getting people together, whether it's at the block level or the municipality level, and people feed off each other, they give each other ideas, it's creating social norms, which is “other people” in a positive direction instead of a negative direction. What we have up here in Vancouver is called the Blue Box program, that's when recycling started at the doorstep level in the 70s. That started with some women in North Vancouver having coffee together and saying, “What the hell, we're throwing out all this paper, what can we do?” And they got the municipality to spend money, because there's a capital cost of starting up those kinds of programs. And where did it start, though? With people meeting and having coffee together, and saying “Let's figure this out.” So that's one thing.

The second thing is, I always tell people if you're not at the table, you're not in the policy, and that can be at the organizational level, in the school or the workplace, it can be at the local counsel or municipal level, it could be at the state level, the federal level. What's your comfort level in terms of talking to other people? It could be just within an office, and so it's to create the table, and then to be at the table, and that's where it starts. So it's the social thing, I think, that's the most important.

But I could talk about a lot of other things. There's a big movement in Canada for universities to divest their pension plans, that's another kind of thing, there's certainly getting more information about there, that's the ignorance, and there's a fresh message idea, to counteract the same “Oh, I've heard about climate change before,” and I guess that's your job, the fresh message idea. I think every one of these has some kind of solution or direction connected with it.

Shares