At six in the morning on Sunday, 12 March, a procession snaked toward the bronze doors of St. Peter’s. Swiss Guards led the line, followed by barefoot friars with belts of rope. Pius took his place at the end, borne on a portable throne. Ostrich plumes stirred silently to either side, like quotation marks.

Pius entered the basilica to a blare of silver trumpets and a burst of applause. Through pillars of incense he blessed the faces. At the High Altar, attendants placed on his shoulders a wool strip interwoven with black crosses.

Outside, police pushed back the crowds. People climbed onto ledges and balanced on chimneys, straining to see the palace balcony.

At noon Pius emerged. The cardinal deacon stood alongside him. Onto Pacelli’s dark head he lowered a crown of pearls, shaped like a beehive. “Receive this Tiara,” he said, “and know that you are the father of kings, the ruler of the world.”

Germany’s ambassador to the Holy See, Diego von Bergen, reportedly said of the ceremony: “Very moving and beautiful, but it will be the last.”

*

As Pacelli was crowned, Hitler at tended a state ceremony in Berlin. In a Memorial Day speech at the State Opera House, Grand Admiral Erich Raeder said, “Wherever we gain a foothold, we will maintain it! Wherever a gap appears, we will bridge it! . . . Germany strikes swiftly and strongly!” Hitler reviewed honor guards, then placed a wreath at a memorial to the Unknown Soldier. That same day, he issued orders for his soldiers to occupy Czechoslovakia.

On 15 March the German army entered Prague. Through snow and mist, on ice-bound roads, Hitler followed in his three-axel Mercedes, its bulletproof windows up. Himmler’s gang of 800 SS officers hunted undesirables. A papal agent cabled Rome, with “details obtained confidentially,” reporting the arrests of all who “had spoken and written against the Third Reich and its Führer.” Soon 487 Czech and Slovak Jesuits landed in prison camps, where it was “a common sight,” one witness said, “to see a priest dressed in rags, exhausted, pulling a car and behind him a youth in SA [Storm Troop] uniform, whip in hand.”

Hitler’s seizure of Czechoslovakia put Europe in crisis. He had scrapped his pledge to respect Czech integrity, made at Munich six months before, which British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain said guaranteed “peace in our time.” Now London condemned “Germany’s attempt to obtain world domination, which it was in the interest of all countries to resist.” Poland’s government, facing a German ultimatum over the disputed Danzig corridor, mobilized its troops. On 18 March, the papal agent in Warsaw reported “a state of tension” between the Reich and Poland “which could have the most serious consequences.” Another intelligence report reaching the Vatican called the situation “desperately grave.”

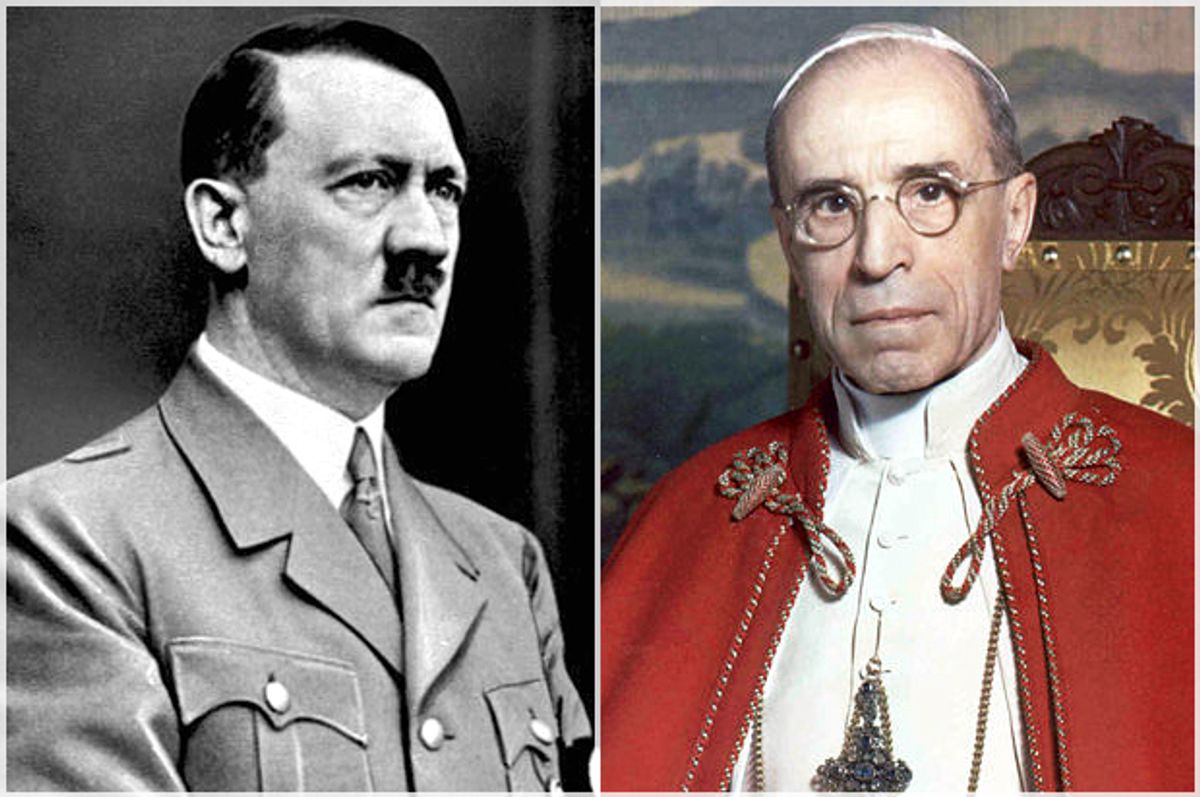

Perhaps no pope in nearly a millennium had taken power amid such general fear. The scene paralleled that in 1073, when Charlemagne’s old empire imploded, and Europe needed only a spark to burn. “Even the election of the pope stood in the shadow of the Swastika,” Nazi labor leader Robert Ley boasted. “I am sure they spoke of nothing else than how to find a candidate for the chair of St. Peter who was more or less up to dealing with Adolf Hitler.”

*

The political crisis had in fact produced a political pope. Amid the gathering storm, the cardinals had elected the candidate most skilled in statecraft, in the quickest conclave in four centuries. His long career in the papal foreign service made Pacelli the dean of Church diplomats. He had hunted on horseback with Prussian generals, endured at dinner parties the rants of exiled kings, faced down armed revolutionaries with just his jeweled cross. As cardinal secretary of state, he had discreetly aligned with friendly states, and won Catholic rights from hostile ones. Useful to every government, a lackey to none, he impressed one German diplomat as “a politician to the high extreme.”

Politics were in Pacelli’s blood. His grandfather had been interior minister of the Papal States, a belt of territories bigger than Denmark, which popes had ruled since the Dark Ages. Believing that these lands kept popes politically independent, the Pacellis fought to preserve them against Italian nationalists. The Pacellis lost. By 1870 the pope ruled only Vatican City, a diamond-shaped kingdom the size of a golf course. Born in Rome six years later, raised in the shadow of St. Peter’s, Eugenio Pacelli inherited a highly political sense of mission. As an altar boy, he prayed for the Papal States; in school essays, he protested secular claims; and as pope, he saw politics as religion by other means.

Some thought his priestly mixing in politics a contradiction. Pacelli contained many contradictions. He visited more countries, and spoke more languages, than any previous pope—yet remained a homebody, who lived with his mother until he was forty-one. Eager to meet children, unafraid to deal with dictators, he was timid with bishops and priests. He led one of the planet’s most public lives, and one of its loneliest. He was familiar to billions, but his best friend was a goldfinch. He was open with strangers, pensive with friends. His aides could not see into his soul. To some he did not seem “a human being with impulses, emotions, passions”—but others recalled him weeping over the fate of the Jews. One observer found him “pathetic and tremendous,” another “despotic and insecure.” Half of him, it seemed, was always counteracting the other half.

A dual devotion to piety and politics clove him deeply. No one could call him a mere Machiavellian, a Medici-pope: he said Mass daily, communed with God for hours, reported visions of Jesus and Mary. Visitors remarked on his saintly appearance; one called him “a man like a ray of light.” Yet those who thought Pius not of this world were mistaken. Hyperspirituality, a withdrawal into the sphere of the purely religious, found no favor with him. A US intelligence officer in Rome noted how much time Pius devoted to politics and how closely he supervised all aspects of the Vatican Foreign Office. While writing an encyclical on the Mystical Body of Christ, he was also assessing the likely strategic impact of atomic weapons. He judged them a “useful means of defense.”

Even some who liked Pacelli disliked his concern with worldly power. “One is tempted to say that attention to the political is too much,” wrote Jacques Maritain, the French postwar ambassador to the Vatican, “considering the essential role of the Church.” The Church’s essential role, after all, was to save souls. But in practice, the spiritual purpose entailed a temporal one: the achievement of political conditions under which souls could be saved. Priests must baptize, say Mass, and consecrate marriages without interference from the state. A fear of state power structured Church thought: the Caesars had killed Peter and Paul, and Jesus.

The pope therefore did not have one role, but two. He had to render to God what was God’s, and keep Caesar at bay. Every pope was in part a politician; some led armies. The papacy Pacelli inherited was as bipolar as he was. He merely encompassed, in compressed form, the existential problem of the Church: how to be a spiritual institution in a physical and highly political world.

It was a problem that could not be solved, only managed. And if it was a dilemma which had caused twenty centuries of war between Church and state, climaxing just as Pacelli became pope, it was also a quandary that would, on his watch, put Catholicism in conflict with itself. For the tectonic pull of opposing tensions, of spiritual and temporal imperatives, opened a fissure in the foundations of the Church that could not be closed. Ideally, a pope’s spiritual function ought not clash with his political one. But if and when it did, which should take precedence? That was always a difficult question—but never more difficult than during the bloodiest years in history, when Pius the Twelfth would have to choose his answer.

*

On 1 September 1939, Pius awoke at around 6:00 a.m. at his summer residence, Castel Gandolfo, a medieval fortress straddling a dormant volcano. His housekeeper, Sister Pascalina, had just released his canaries from their cages when the bedside telephone rang. Answering in his usual manner, “E’qui Pacelli” (“Pacelli here”), he heard the trembling voice of Cardinal Luigi Maglione, relaying intelligence from the papal nuncio in Berlin: fifteen minutes earlier, the German Wehrmacht had surged into Poland.

At first Pius carried on normally, papally. He shuffled to his private chapel and bent in prayer. Then, after a cold shower and an electric shave, he celebrated Mass, attended by Bavarian nuns. But at breakfast, Sister Pascalina recalled, he probed his rolls and coffee warily, “as if opening a stack of bills in the mail.” He ate little for the next six years. By war’s end, although he stood six feet tall, he would weigh only 125 pounds. His nerves frayed from moral and political burdens, he would remind Pascalina of a “famished robin or an overdriven horse.” With the sigh of a great sadness, his undersecretary of state, Domenico Tardini, reflected: “This man, who was peace-loving by temperament, education, and conviction, was to have what might be called a pontificate of war.”

In war the Vatican tried to stay neutral. Because the pope represented Catholics in all nations, he had to appear unbiased. Taking sides would compel some Catholics to betray their country, and others their faith.

But Poland was special. For centuries, the Poles had been a Catholic bulwark between Protestant Prussia and Orthodox Russia. Pius would recognize the exiled Polish government, not the Nazi protectorate. “Neutrality” described his official stance, not his real one. As he told France’s ambassador when Warsaw fell: “You know which side my sympathies lie. But I cannot say so.”

As news of Poland’s agony spread, however, Pius felt compelled to speak. By October, the Vatican had received reports of Jews shot in synagogues and buried in ditches. The Nazis, moreover, were targeting Polish Catholics as well. They would eventually murder perhaps 2.4 million Catholic Poles in “nonmilitary killing operations.” The persecution of Polish Gentiles fell far short of the industrialized genocide visited on Europe’s Jews. But it had near-genocidal traits and prepared the way for what followed.

On 20 October Pius issued a public statement. His encyclical Summi Pontificatus, known in English as Darkness over the Earth, began by denouncing attacks on Judaism. “Who among ‘the Soldiers of Christ’ does not feel himself incited to a more determined resistance, as he perceives Christ’s enemies wantonly break the Tables of God’s Commandments to substitute other tables and other standards stripped of the ethical content of the Revelation on Sinai?” Even at the cost of “torments or martyrdom,” he wrote, one “must confront such wickedness by saying: ‘Non licet; it is not allowed!’” Pius then stressed the “unity of the human race.” Underscoring that this unity refuted racism, he said he would consecrate bishops of twelve ethnicities in the Vatican crypt. He clinched the point by insisting that “the spirit, the teaching and the work of the Church can never be other than that which the Apostle of the Gentiles preached: ‘there is neither Gentile nor Jew.’”

The world judged the work an attack on Nazi Germany. “Pope Condemns Dictators, Treaty Violators, Racism,” the New York Times announced in a front-page banner headline. “The unqualified condemnation which Pope Pius XII heaped on totalitarian, racist and materialistic theories of government in his encyclical Summi Pontificatus caused a profound stir,” the Jewish Telegraphic Agency reported. “Although it had been expected that the Pope would attack ideologies hostile to the Catholic Church, few observers had expected so outspoken a document.” Pius even pledged to speak out again, if necessary. “We owe no greater debt to Our office and to Our time than to testify to the truth,” he wrote. “In the fulfillment of this, Our duty, we shall not let Ourselves be influenced by earthly considerations.”

It was a valiant vow, and a vain one. He would not use the word “Jew” in public again until 1945. Allied and Jewish press agencies still hailed him as anti-Nazi during the war. But in time, his silence strained Catholic-Jewish relations, and reduced the moral credibility of the faith. Debated into the next century, the causes and meaning of that silence would become the principal enigma in both the biography of Pius and the history of the modern Church.

Judging Pius by what he did not say, one could only damn him. With images of piles of skeletal corpses before his eyes; with women and young children compelled, by torture, to kill each other; with millions of innocents caged like criminals, butchered like cattle, and burned like trash—he should have spoken out. He had this duty, not only as pontiff, but as a person. After his first encyclical, he did reissue general distinctions between race-hatred and Christian love. Yet with the ethical coin of the Church, Pius proved frugal; toward what he privately termed “Satanic forces,” he showed public moderation; where no conscience could stay neutral, the Church seemed to be. During the world’s greatest moral crisis, its greatest moral leader seemed at a loss for words.

But the Vatican did not work by words alone. By 20 October, when Pius put his name to Summi Pontficatus, he was enmeshed in a war behind the war. Those who later explored the maze of his policies, without a clue to his secret actions, wondered why he seemed so hostile toward Nazism, and then fell so silent. But when his secret acts are mapped, and made to overlay his public words, a stark correlation emerges. The last day during the war when Pius publicly said the word “Jew” is also, in fact, the first day history can document his choice to help kill Adolf Hitler.

Excerpted from "Church of Spies: The Pope's Secret War Against Hitler" by Mark Riebling. Published by Basic Books, a division of the Perseus Book Group. Copyright 2015 by Mark Riebling. Reprinted with permission of the publisher. All rights reserved.

Shares