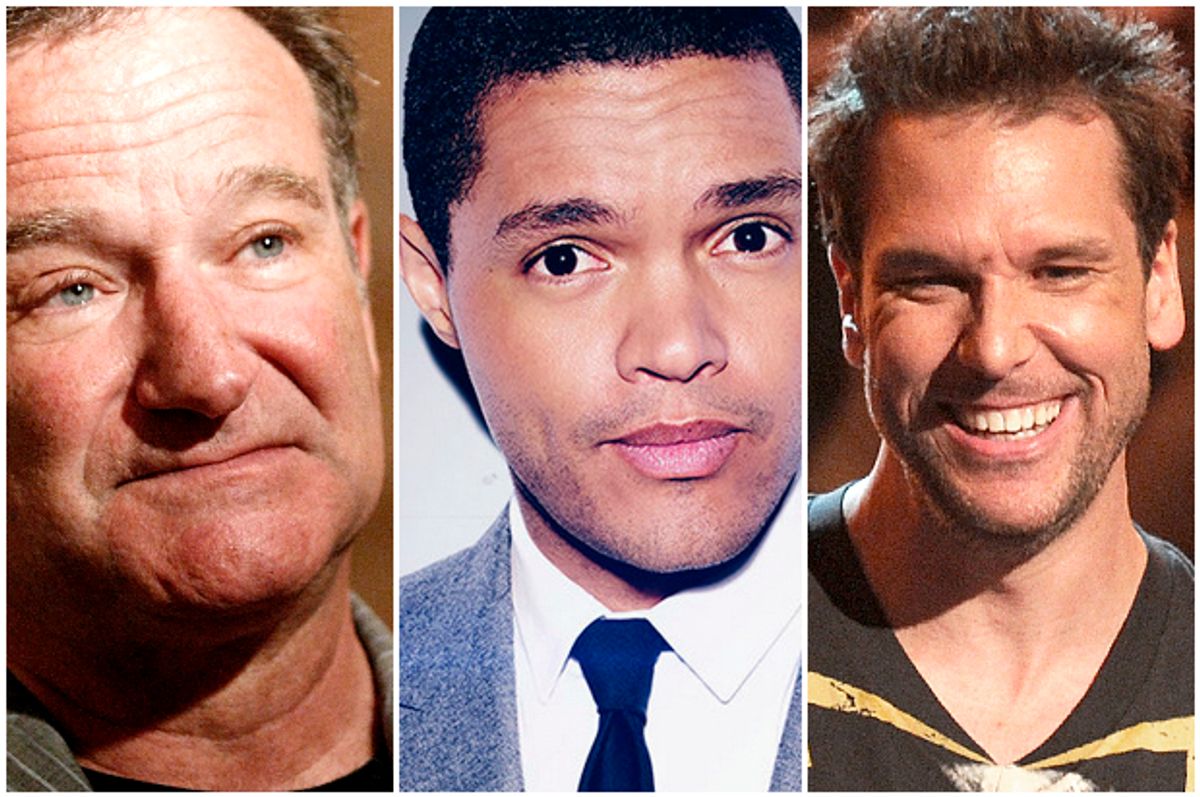

Since the announcement in March that up-and-coming South African comedian Trevor Noah would succeed Jon Stewart as host of the "Daily Show," Noah has come under his fair share of scrutiny for things like years-old tweets and drooping ratings. Last week, the Hollywood Reporter upped the ante with a report implying that Noah may be a joke thief. Noah’s 20-minute stand-up set at a political convention last weekend in L.A. included a bit quite similar to a joke from Dave Chappelle’s 1998 HBO special. Both jokes centered on differences in racism across cultures, and used the phrase “racism connoisseur” — a degree of similarity that raised speculation about whether Noah has sticky comedic fingers.

As THR and other outlets pointed out, Noah has faced other accusations of joke-theft in the past. But Noah is only the latest in a long line of comedians to face heat for stealing gags. Just as stand-up comedy has evolved as an art form since its 19th century beginnings, so too have the ethics and repercussions of poaching other peoples’ material. While these discussions typically unfolded within the comedy community in the past, social media makes it easier than ever for joke theft charges to go viral, but the impact that will have on would-be thieves remains to be seen.

Historians peg the birth of stand-up comedy to the late-19th century vaudeville era, when a variety of acts including burlesque dancers, musicians, jugglers and sketch comedy duos toured theaters across the country. Vaudeville shows specifically catered to the sensibilities of the multiethnic working class, which meant the sets had to be fast-paced, fun and easy to understand. These criteria gave rise to slapstick based on simple tropes, as well as to the idea that performers could “borrow” and “build off of” other acts. This permissive attitude about joke theft was probably at least partially fatalist — it’s awfully tough to prove a joke’s origin when acts are constantly touring from town-to-town. But the nature of the shows likely encouraged this behavior as well, since comics who recycled familiar bits had a better chance of satisfying both censorious theaters and audiences who spoke limited English. The “pie in the face” gag began as a vaudeville go-to, as did “The Aristocrats,” the classic dirty joke comics still put their own spins on today.

As more and more comedic vaudevillians began to performing material “in one” — that is, standing alone on a stage — the free-wheeling rules of the past no longer fit. Then the rapid rise of moving pictures thoroughly disrupted the vaudeville industry: theatre after theatre closed, since they couldn't compete with bargain prices at the cinema. Comics were competing more and more for dwindling live-performance slots, as well as to be cast in film, and having highly original material was an obvious way to set oneself apart from the pack. By the time vaudeville finally flatlined in the early 1930s, comedians' bits were being filmed to be shown in pre-movie reels, making it slightly harder for aspiring copycats to simply smuggle ideas over to the next town.

The open source ethos of the early vaudeville days have led some to argue that joke theft is no big deal — and as cases like “The Aristocrats” illustrate, can even spark creative oneupmanship. But nearly all comedians reject this argument. Patton Oswalt even once reminded Time Magazine that even vaudeville legend W.C. Fields famously “beat the living s**t” out of anyone who copied his act. Besides — the vaudeville rules regulated an art form that was economically and creatively very different than modern stand-up. In a cut-throat industry where up-and-comers compete ferociously for five-minute TV spots, the stakes of a lifted joke are far higher than two similar slapstick acts getting paid in two different cities where no one has televisions.

If the advent of film helped to stigmatize joke theft, it certainly didn't stop it. The debuts of the first comedy album in 1958 and the first comedy club in 1963 both entrenched the idea that a stand-ups success would be determined not only by how good their material was, but how much of it they had. A vaudevillian could happily cash-in with the same 10 minute set in 50 different cities — but a stand-up would need a solid hour to headline a club or record an album. The quantity of material a given comic had was now directly tied to their livelihoods. This meant that a minute of stand-up was essentially commodified as comedic currency, to be safeguarded by those who have it, and snatched by those who don’t.

This can still be the case today. In one 2013 viral essay, Oswalt, perhaps the comedy world’s most outspoken voice against joke theft, described watching a young comedian passing off massive chunks of a buddy’s set as his own to score more lucrative feature gigs. When confronted, the thief insisted that he needed to steal, since he couldn't possibly clear 30 minutes using only his own material. Whatever pay boost he got as a feature instead of an opener was money made off the sweat of funnier brows. Frustration with that same entitled calculus sparked comedians’ high-profile clash with the “Fat Jew,” who earlier in 2015 made headlines for successfully monetizing an Instagram feed comprised solely of pilfered jokes. Many outlets characterized the controversy as being over proper attribution, but it was really over the fact that he was benefiting from a brand he didn't do anything to create. For most comedians, Fat Jew’s penance wouldn't just be attribution, it would be writing his own damn jokes.

Aside from economics, most comedians are moved by convictions of creative ownership over their own work. Stand-up has grown into a far more bonafide art form than its silly slapstick predecessor, further affirming the immorality of thievery. But even if stand-ups have long agreed that stealing jokes is wrong, they are still faced with an obvious problem. What exactly are they supposed to do about it?

While other fields may be governed by strict rules regarding plagiarism and can enforce copyright laws through the courts, stand-up comedians have little formal recourse when someone helps themselves to their big closer. The problems with copyright as related to stand-up comedy were succinctly explained by Slate: “Copyright law defends the expression of an idea, but not the idea itself. So even if somebody stole your joke about bad airline food, there’s little you can do if that person tells the same joke with slightly differently wording—no one owns the idea of mocking bad airline food. And even when a comedian does have a legal basis to accuse somebody of copyright infringement, it can be expensive to do anything about it.” (Indeed, it’s hard to imagine an open mic comic who makes ends meet waiting tables retaining a copyright lawyer to protect his Tinder joke.)

Industry professionals aren't very interested in defending the sanctity of comedy either, so the business of policing joke theft falls largely to comedians themselves. In 2007, researchers at University of Virginia Law School produced a report on strategies the comedy community implements to reduce theft and hold offenders accountable. While they found no examples of comic-on-comic copyright suits, they nonetheless concluded that stand-ups had managed to hone a well-functioning system to preserve their art. Punishments for joke thieves can range from badmouthing and tarnished reputations, to coordinated “blackballing,” to the rare-but-possible physical altercations in the style of W.C. Fields.

Examples of just how comedians’ interactions with thieves play out stretch back for decades, many of which were recounted by Larry Getlen in a 2007 feature for Radar Magazine. In the 1980s, comics at the Hollywood Improv reportedly devised a blinking light system to warn performers when known joke thieves showed up. (Among the most notorious was Robin Williams, who was even said to pay off comics who complained about stolen bits.)

At the L.A. Comedy Store in 2007, comedian Joe Rogan went so far as to interrupt Carlos Mencia onstage over his habit of rampant joke theft. Rogan also posted a video of the confrontation online, harkening an era in which discussions over joke theft frequently happen publicly online. It’s quite possible this degree of transparency applies pressure to industry gatekeepers, who kept hiring Carlos “Menstealia” for years until the public began to turn on him.

Of course, video can have a “gotcha” effect on stand-up beyond cases of premeditated, filmed ambushes of notorious thieves. Some people believe video may finally be having the effect hypothetically imagined back when film began edging out vaudeville. They contend that the fact that bits can be uploaded and watched online may convince potential thieves not to bother, or act as an insurance policy for comedians wishing to ward off vultures. If all else fails, side-by-side evidence can allow a wider audience to weigh in — like with the Hollywood Reporter story comparing Noah to Chapelle.

But objective truth isn't always so easy to come by. Joke theft has never been as straight-forward a crime as, say, jewelry theft, because accusations of “joke theft” can point to several different things. Certainly, there are deplorable instances of outright, consciously purloined material. But there are also many innocent cases of what comedians call “parallel thought,” when people simply happen to come up with the same gag independently. (Last week’s announcement that Playboy would cease publishing nudes, for example, sparked endless “now you can really read it for the articles!” quips on social media.) And then there’s an ambiguous “other” category that includes things like “unconscious plagiarism,” when comics subconsciously internalize someone else’s joke, or material born out of conversations between comics where the actual owner might be ambiguous. Art Markman, a psychology professor at University of Texas, confirmed in an email that this phenomenon exists when it comes to generating creative ideas.

Leveraging public opinion against joke theft can be effective in cases like Mencia’s, when it’s time to dole out comedy justice to those who really deserve it. But when it comes to the considerable grey area beyond the realm of copy-and-paste, the best judgment certainly lies with the people who have been negotiating these issues all along: the comedians themselves. Joke theft is a severe charge that impugns a person’s character and talent. Accusations have almost certainly branded some comics undeservedly — damage easier than ever to do in the age of social media. It’s impossible to say what happened in Noah’s case, but parallel thought or unconscious plagiarism seems likely.

Perhaps the most interesting rumination on joke theft in the digital era unfolded in a 2011 episode of "Louie" that featured Dane Cook, whom Louis CK had been accusing of joke theft since 2005. In the episode, the two men hash out a barely fictionalized version of the issue in a way that feels honest and cathartic. When Louis asks Dane to help score concert tickets for his daughter, Dane agrees on the condition that Louis publicly admit Dane never stole his bits. When Louis protests that Dane did steal, Dane retorts: “Dude! Why would I steal three jokes from you when I have hours of material. Why? Why! Why would I do that? Risk my reputation! […] The one thing that, like, really just, gets to me, is the whole thing about people saying that I stole the joke about the itchy asshole. Because I get an itchy asshole. A lot. So for you to think you're the only person who got an itchy asshole in America? I mean, that's bullshit.”

In doing so, CK added nuance to a narrative that had all but condemned Cook. Whatever happened between the two comedians, the episode made it clear just how much their art and community means to them, and how difficult a firm resolution can be.

Shares