This week’s elections featured a number of losses for progressive politics, but there was at least one silver lining: They showed that when voters have an opportunity to reject big donor politics, they overwhelmingly will. In both Maine and Seattle, voters approved ballot measures to implement or strengthen public financing, an important reform that can increase the diversity of the donor pool and reduce the power of big money in politics. In Maine, the ballot initiative would boost funds for qualifying candidates and require more disclosure of some political spending. In Seattle, Initiative 122 implements a first of its kind voucher program, which gives each voter $25 vouchers that they can give to their preferred candidate for mayor, city council and city attorney. The initiative also bars contribution from companies or individuals that have large contracts with the city.

Why do these programs matter? A recent study from the Institute for Southern Studies of North Carolina shows that the donor class is overwhelmingly white, far whiter than the general public. Alex Kotch, author of the report, writes, “95 percent of the largest North Carolina donors to key federal races in the 2014-2016 election cycles were white, while non-Hispanic whites make up 65 percent of the state population.” A study of Seattle’s 2013 election suggests that while Seattle is 67 percent non-Hispanic white, the neighborhoods from which more than half of contributions came from were 80 percent white.

There is evidence that public financing would increase the diversity of the donor base. A study of New York City’s 2009 municipal election finds that “donors giving $10 or less live in neighborhoods that are more racially diverse than the city as a whole.” Research suggests that the city’s public matching system (which uses public funds to match small donations) increased the diversity of the city’s donor pool. Other research suggests that the small donor pool tends to be more racially diverse than the large donor pool and that donors as a whole tend to be whiter than the general population.

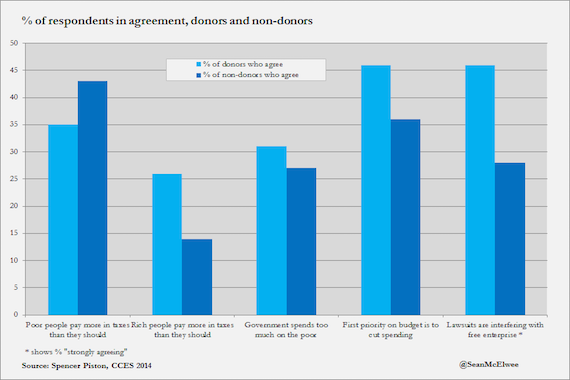

The donor pool also has differing preferences from the general population. As I’ve noted several times, there is ample evidence that donors are pulling the nation to the right on economic issues, exacerbating rising inequality. Donors of all stripes tend to be more economically conservative as the chart below, made with data from the 2014 Cooperative Congressional Election Study shows.

A study by Didi Kuo and Nolan McCarty finds, “Donors are also more supportive of low taxes and freer trade. Donors were slightly less supportive of the Affordable Care Act, which overhauled the American health care system to promote universal coverage.” One study by a group of scholars spearheaded by Wesley Joe of the Campaign Finance Institute finds, “Large donors are more likely than small donors to give in the interest of advancing their own narrow economic concerns, as distinct from a more general concern about the economy.” The chart below shows this. Large donors are far more likely to report donating for “material” reasons (advancing their own material interests), while small donors tend to donate for “purposive reasons” (ideological alignment and which candidate they feel would be better for the economy). Their study also finds that small donors are closer to the opinions of non-donors than large donors, with large donors being more economically conservative.

There is evidence that public financing frees politicians from the influence of the donor class. A study by Peter Francia and Paul Herrnson finds that candidates who are publicly financed spend less time raising money than privately funded counterparts. Miller finds that publicly financed candidates spend more time interacting with the general public. That matters, because as Connecticut Senator Chris Murphy has said of fundraising for his campaign, “I talked a lot more about carried interest inside of that call room than I did in the supermarket . . . [The people I’m calling] have fundamentally different problems than other people.”

A Demos study of public financing in Connecticut finds that, “In the short time since public financing has been in place, Connecticut has seen an increase in diversity in the legislature, a more substantive legislative process, and more freedom from big donor and special interests.”

The experience of one former legislator is telling. He tells Demos,

“Before public financing, during the session…there were ‘shakedowns’ where lobbyists and corporate sponsors had events and you as a legislator had to go. That’s no longer a part of the reality.”

There are other benefits of public financing. In his book, "Subsidizing Democracy," Michael Miller finds, that roll-off (when individuals vote for the most high-profile contests but don’t complete their ballot) appears to be lower when at least one candidate ran with public financing. If public financing does increase turnout, that would have further political benefits for Laws for political equality help increase economic equality. A study by Patrick Flavin finds that, “states with stricter campaign finance laws devote a larger proportion of their annual budget to public welfare spending in general and to cash assistance programs in particular.” Thus, by limiting big money in politics,

Public financing of elections is popular and, given the Supreme Court decisions over the last few decades, one of the few options left to reformers that want to make America live up to its democratic values. The ballot initiatives in Seattle and and Maine provide a glimmer of hope in the often bleak news about the increasing power of the donor class.

Shares