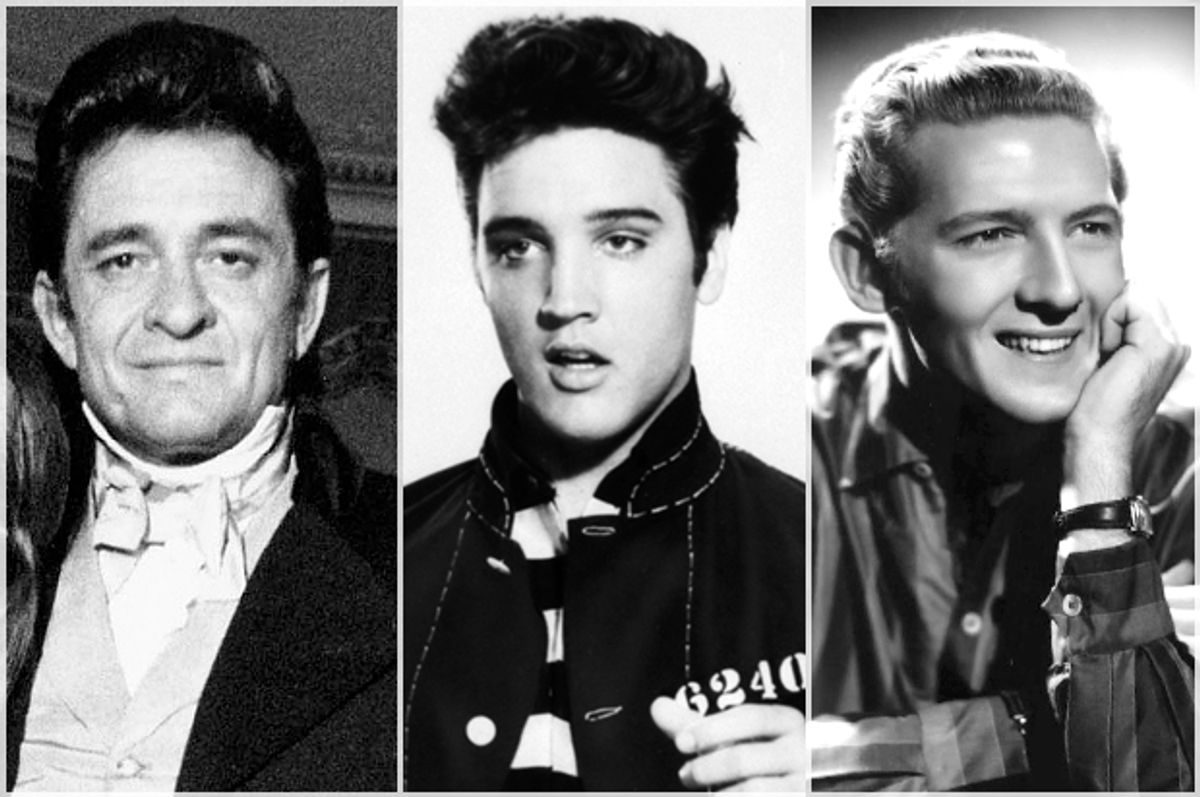

The music writer Peter Guralnick has spent his long and celebrated career warming up for his new book. The author of books about country, blues, soul, and a definitive, two-volume biography of Elvis Presley, he’s now turned to one of the great taproots of American music. “Sam Phillips: The Man Who Invented Rock 'n' Roll” describes the life and cultural context of the Sun Records founder. And it looks at Phillips’s relationships with Howlin’ Wolf, Ike Turner (whose “Rocket 88” is sometimes called the first rock song), Jerry Lee Lewis, Johnny Cash and Elvis Presley, all of whom he recorded.

“It’s worth pausing, for a moment, to consider how lucky it was that Presley walked into Phillips’s studio and not someone else’s,” Dwight Garner wrote in a rave New York Times review of the Guralnick book. “Another producer (that term had not yet come into use in the record industry) might have put him to work singing country-pop ditties with string sections. He might have been another Eddy Arnold.”

We’re also lucky that Guralnick – who wrote the script for a Phillips documentary made by A&E – tackled Phillips’s complex life and times. We spoke to him from his home near Boston. The interview has been lightly edited for clarity.

The subtitle of your book is “The Man Who Invented Rock ‘n’ Roll.” I don’t think you’re the first person to call him that, and the phrase served as the title for a documentary years ago. Overall, give us a sense of how important Phillips was to the birth and early evolution of the music.

What I think was remarkable about Sam, besides the fact that from a tiny little storefront studio in Memphis, so much music came out of such a tiny space, from something that was essentially a one-man operation. From Elvis to Carl Perkins to Johnny Cash to Jerry Lee Lewis, [he created] what was essentially the dominant strain of rock ‘n’ roll during the first few years of its existence.

What I think is extraordinary about Sam is that he had a vision for rock ‘n’ roll long before the music existed, long before he was even able to give expression to it… Years before he even conceived of building a recording studio, he conceived a music that could bridge all gaps, that could deny category… An African-American-based music that could leap across the chasms of race and social origin and class. And when he opened his studio, the first hit he had come out was [Ike Turner’s] “Rocket 88.” It doesn’t matter how you label it – the fact is, it was an extraordinary hit, it sold over 100,000 copies.

In his first public utterances, in the Memphis Commercial Appeal, he spoke of that same vision. Of “Rocket 88” being the kind of music that could appeal to all kinds, that could reach a mainstream audience, that could bridge that gap. While the record may not have fully realized what we envisioned for it, that was clearly what he was looking to achieve from the moment he started recording anyone.

He had the same vision for Howlin’ Wolf.

What was the racial situation like in the South when he was growing up? How much black music was he exposed to?

Anybody growing up in the South would be exposed to a lot of black music unless they were deaf to it, either for reasons of prejudice or because they couldn’t hear. The South has always been different from the North because while the legal system was always tangled in segregation, everything about day-to-day life argued against the formal practice. Whereas in the North, where segregation was not institutionalized, there was far greater separation.

So for Sam, growing up initially on that 323-acre farm outside of Florence, Alabama – his father rented the farm, but didn’t own it, and couldn’t hold onto it after the depression hit – he had sharecroppers, both black and white, working in the fields. Sam worked with them. What he was drawn to most of all was the sounds that were all around him – it could be a whippoorwill, it could be a hoe striking rock, it could be the music that came primarily from the black sharecroppers.

But he was also acutely aware of the racial disparities which existed. And we’re talking about a 6- or 7-year-old kid. When I spoke to his family… they weren’t altogether thrilled by the manner in which he expressed himself. Or the views he expressed.

He was drawn to this music; he was drawn to all sorts of music. H loved John Philip Sousa. He loved hillbilly music. He loved gospel music.

What he was most drawn to was black music of all kinds. After he went to church with his family, he would go to the black church, a block and a half from the church he attended… He described himself as being spellbound by the music coming out of there, particularly in the summer when the windows were open and you could hear every beat of the music.

So when he opened his studio it was explicitly to give some of “those great Negro singers of the South an opportunity to record” – I’m not getting the quote quite right – where previously they’d not had one.

How central was that to his ambition to open a studio?

That was entirely what he opened his studio for. This was the Memphis Recording Service, not Sun Records.

But he was stymied – how do you get some of these African-American artists to record? Joe Hill Louis, the great one-man-band who performed frequently on Beale Street, just wandered into the studio one day and asked him what he was doing. Sam said, Well, I’m opening a recording studio, and explained what his purpose was. And Lewis said, That’s just what Memphis needs. And Joe Hill Louis became Sam’s ambassador to the [black] community.

I’ve spoken about “Rocket 88.” Ike Turner bumped into a friend, Riley B. King [B.B. King], who told him, You should go up to Memphis – I’m making records with this man, Sam Phillips.

How did the rockabilly musicians find the place?

Elvis was the first, and it was really in the wake of Elvis that everybody else came in. Jerry Lee Lewis talks about reading an article in one of the fan magazines about Elvis Presley, that spoke about Sam Phillips and how he’d recorded B.B. King and Howlin’ Wolf. Most of the so-called rockabilly singers were well aware of B.B. King.

Elvis came into the studio – there’s no way of proving this – in the immediate aftermath of a story that ran in the Memphis Press-Scimitar, I think it was, about the Prisonaires, a group Sam had just recorded in July of 1953, who were incarcerated in the Tennessee State Penitentiary in Nashville. They recorded there and a reporter described Sam as a man open to talent of any kind, who was looking for original talent, would record people no one else would record.

I don’t think there’s any doubt, this is what emboldened Elvis to go in there. And his excuse for going in there was to cut a personal record – one side for three dollars and two sides for four dollars. He was trying to put himself in the way of discovery of this man he’d heard about. Elvis was such a walking encyclopedia of music of every type – he was an ethnomusicologist without a degree. And it was the openness of Mr. Phillips.

That drew him to the studio, and then he kept coming back again and again… Then Sam set up a rehearsal with Scotty Moore, and that’s what, on July 5, 1954, led to “That’s All Right.” It was a torturous process; it took a lot of patience from the man in the booth. It’s not that he didn’t recognize Elvis’s talent – he didn’t recognize the thing that best expressed Elvis’s talent, or had any hope of selling.

That’s a great song.

It was through the success that Elvis enjoyed throughout the South, particularly the mid-South – he was a star in the region – that led to everyone from Johnny Cash to Carl Perkins, to lesser-known talents, they were all drawn to the studio. It wasn’t just the success Elvis had – it was the original sound coming out of the studio.

You got to know Phillips a bit, starting in the ’70s. What was it like to be around him?

It was great – the most unexpected and biggest fun in the world. He was probably the most charismatic man I ever met. From the moment I met him in ’79. I was inspired by that first meeting. I had no idea that what he would talk about would so encapsulate a philosophy of the creative life. He’s talking about having the courage of your convictions, doing everything in your powers to realize your vision…. He was a person insistent on his originality; he wasn’t a rude person but he wasn’t interested in small talk. As he said, “I love chaos.” It was a remarkable experience knowing him over 25 years…. He kept his distance; he didn’t give himself over all at once.

He was a solitary person, like so many people who lived his life in public. There was nothing that could have been more challenging or more fun.

Shares