The opening of the Chilean filmmaker Alejandro Jodorowsky’s proposed adaptation of Frank Herbert’s 1965 novel, Dune, would have been the most ambitious single shot in cinema.

It was to begin outside a spiral galaxy and then continuously track in, into the blazing light of billions of stars, past planets and wrecked spacecraft. The music was to be written and performed by Pink Floyd. The scene would have continued past convoys of mining trucks designed by the crème of European science fiction and surrealist artists, including Chris Foss, Moebius and H.R. Giger. We would see bands of space pirates attacking these craft and fighting to the death over their cargo, a life-giving drug known as Spice. Still the camera would continue forwards, past inhabited asteroids and the deep-space industrial complexes which refine the drug, until it found a small spacecraft carrying away the end result of this galactic economy: the dead bodies of those involved in the spice trade.

The shot would have been a couple of minutes long and would have established an entire universe. It was a wildly ambitious undertaking, especially in the pre-computer graphics days of cinema. But that wasn’t going to deter Jodorowsky.

This scale of Jodorowsky’s vision was a reflection of his philosophy of filmmaking. “What is the goal of life? It is to create yourself a soul. For me, movies are an art more than an industry. The search for the human soul as painting, as literature, as poetry: movies are that for me,” he said. From that perspective, there was no point in settling for anything small. “My ambition for Dune was for the film to be a Prophet, to change the young minds of all the world. For me Dune would be the coming of a God, an artistic and cinematic God.

"For me the aim was not to make a picture, it was something deeper. I wanted to make something sacred.”

The English maverick theatre director Ken Campbell, who formed the Science Fiction Theatre Company of Liverpool in 1976, also recognised that this level of ambition could arise from science fiction, even if he viewed it from a more grounded perspective. “When you think about it,” he explained, “the entire history of literature is nothing more than people coming in and out of doors. Science fiction is about everything else.”

Jodorowsky began putting a team together, one capable of realising his dream. He chose collaborators he believed to be “spiritual warriors.” The entire project seemed blessed by good fortune and synchronicity. When he decided that he needed superstars like Orson Welles, Salvador Dalí or Mick Jagger to play certain parts, he would somehow meet these people by happenstance and persuade them to agree. But when pre-production was complete, he went to pitch the film to the Hollywood studios.

Jodorowsky pitched Dune in the years before the success of Star Wars, when science fiction was still seen as strange and embarrassing. As impressive and groundbreaking as his pitch was, it was still a science fiction film. They all said “no.”

By the time this genre was first named, in the 1920s, it was already marginalised. It was fine for the kids, needless to say, but critics looked down upon it. In many ways this was a blessing. Away from the cultural centre, science fiction authors were free to explore and experiment. In this less pressured environment science fiction became, in the opinion of the English novelist J.G. Ballard, the last genre capable of adequately representing present-day reality. Science fiction was able to get under the skin of the times in a different way to more respected literature. A century of uncertainty, relative perspectives and endless technological revolutions was frequently invisible to mainstream culture, but was not ignored by science fiction.

* * *

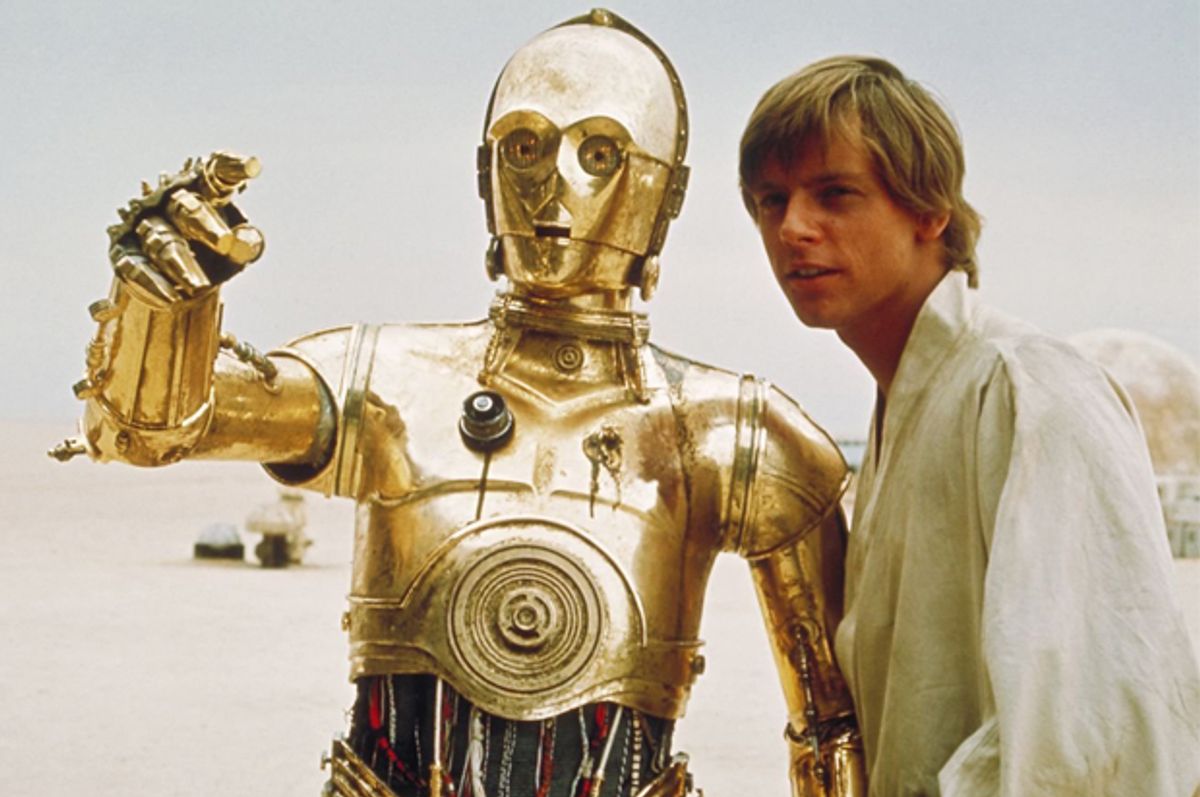

The script for George Lucas’s 1977 movie Star Wars was influenced by The Hero with a Thousand Faces, a 1949 book by the American mythologist Joseph Campbell. Campbell believed that at the heart of all the wild and varied myths and stories which mankind has dreamt lies one single archetypal story of profound psychological importance. He called this the monomyth. As Campbell saw it, the myths and legends of the world were all imperfect variations on this one, pure story structure. As Campbell summarised the monomyth, “A hero ventures forth from the world of common day into a region of supernatural wonder: fabulous forces are there encountered and a decisive victory is won: the hero comes back from this mysterious adventure with the power to bestow boons on his fellow man.”

Campbell found echoes of this story wherever he looked; myths as diverse as those of Ulysses, Osiris or Prometheus, the lives of religious figures such as Moses, Christ or Buddha, and in plays and stories ranging from Ancient Greece to Shakespeare and Dickens. This story is now known as “The Hero’s Journey.” It is a story that begins with an ordinary man (it is almost always a man) in a recognisable world. That man typically receives a call to adventure, encounters an older patriarchal mentor, undergoes many trials in his journey to confront and destroy a great evil, and returns to his previous life rewarded and transformed. George Lucas was always open about the fact that he consciously shaped the original Star Wars film into a modern expression of Campbell’s monomyth, and has done much to raise the profile of Campbell and his work.

Star Wars was so successful that the American film industry has never really recovered. Together with the films of Lucas’s friend Steven Spielberg, it changed Hollywood into an industry of blockbusters, tent-pole releases and high-concept pitches. American film was always a democratic affair which gave the audience what it wanted, and the audience demonstrated what they wanted by the purchase of tickets. The shock with which Hollywood reacted to Star Wars was as much about recognising how out of step with the audience’s interests it had become as it was about how much money was up for grabs. Had it realised this a few years earlier, it might have green-lit Jodorowsky’s Dune.

The fact that Lucas had used Campbell’s monomyth as his tool for bottling magic did not go unnoticed. As far as Hollywood was concerned, The Hero’s Journey was the goose that laid the golden eggs. Studio script-readers used it to analyse submitted scripts and determine whether or not they should be rejected. Screenwriting theorists and professionals internalised it, until they were unable to produce stories that differed from its basic structure. Readers and writers alike all knew at exactly which point in the script the hero needed their inciting incident, their reversal into their darkest hour and their third-act resolution. In an industry dominated by the bottom line and massive job insecurity, Campbell’s monomyth gained a stranglehold over the structure of cinema.

Campbell’s monomyth has been criticised for being Eurocentric and patriarchal. But it has a more significant problem, in that Campbell was wrong. There is not one pure archetypal story at the heart of human storytelling. The monomyth was not a treasure he discovered at the heart of myth, but an invention of his own that he projected onto the stories of the ages. It’s unarguably a good story, but it is most definitely not the only one we have. As the American media critic Philip Sandifer notes, Campbell “identified one story he liked about death and resurrection and proceeded to find every instance of it he could in world mythology. Having discovered a vast expanse of nails for his newfound hammer he declared that it was a fundamental aspect of human existence, ignoring the fact that there were a thousand other ‘fundamental stories’ that you could also find in world mythology.”

Campbell’s story revolves around one single individual, a lowly born person with whom the audience identifies. This hero is the single most important person in the world of the story, a fact understood not just by the hero, but by everyone else in that world. A triumph is only a triumph if the hero is responsible, and a tragedy is only a tragedy if it affects the hero personally. Supporting characters cheer or weep for the hero in ways they do not for other people. The death of a character the hero did not know is presented in a manner emotionally far removed from the death of someone the hero loved. Clearly, this was a story structure ideally suited to the prevailing culture. Out of all the potential monomyths that he could have run with, Campbell, a twentieth-century American, chose perhaps the most individualistic one possible.

The success of this monomyth in the later decades of the twentieth century is an indication of how firmly entrenched the individualism became. Yet in the early twenty-first century, there are signs that this magic formula may be waning. The truly absorbing and successful narratives of our age are moving beyond the limited, individual perspective of The Hero’s Journey. Critically applauded series like The Wire and mainstream commercial hit series such as Game of Thrones are loved for the complexity of their politics and group relationships. These are stories told not from the point of view of one person, but from many interrelated perspectives, and the relationships between a complex network of different characters can engage us more than the story of a single man being brave.

In the twenty-first century audiences are drawn to complicated, lengthy engagements with characters, from their own long-term avatar in World of Warcraft and other online gameworlds to characters like Doctor Who who have a fifty-years-plus history. The superhero films in the “Marvel Cinematic Universe” are all connected, because Marvel understands that the sum is greater than the parts. A simple Hero’s Journey story such as J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Hobbit becomes, when adapted for a twenty-first-century cinema audience, a lengthy trilogy of films far more complex than the original book. We now seem to look for stories of greater complexity than can be offered by a single perspective.

If science fiction is our cultural early-warning system, its move away from individualism tells us something about the direction we are headed. This should grab our attention, especially when, in the years after the Second World War, it became apparent just how dark the cult of the self could get.

Excerpted from "Stranger Than We Can Imagine: Making Sense of the Twentieth Century" by John Higgs. Copyright © 2015 by John Higgs. Reprinted by permission of Counterpoint.

Shares