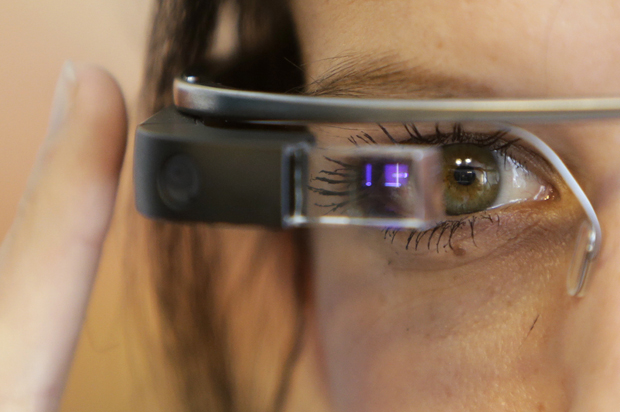

To the delight of geeks everywhere, and the chagrin of everyone else, Business Insider reported earlier this month that Google is resuscitating its much-maligned Glass project under the new name Project Aura. Glass, you might recall, was an ill-fated wearable technology device that some likened to a “dystopian skull accessory.” Promos had touted the benefits of augmented reality and quick access to photo and video capture. With a wink, nod or swipe of the finger, users could purportedly remain “in the here and now” by accessing the Web within their field of vision or seamlessly recording events for later viewing.

Both of these features spawned a tidal wave of parodies on YouTube and late-night comedy shows. Other responses were more serious, addressing the “creepy” factor of personal and corporate surveillance. Glass soon came to symbolize the excesses of Silicon Valley as a whole, and the backlash culminated in a small but well-publicized number of violent street and bar-stool skirmishes between angry bystanders and those who could afford the $1,500 price tag. One such victim, Sarah Slocum, described her experience as a “hate crime” — a comment that further infuriated those she called “Glass haters.” The #Glasshole hashtag emerged as a catch-all for what critics saw as Glass users’ attitude of entitlement and disregard for basic social etiquette. The return of Glass, by whatever name, thrusts these issues back into the spotlight.

The term “Glasshole” points to a much broader set of concerns at the heart of the digital economy. The street-level confrontations between Glass users and anti-gentrification activists in San Francisco are merely a microcosm of growing tensions stemming from privileged access to, and exploitation of, the benefits of digital media technologies. Wearable technologies are unsurprisingly a focal point for debate, since they raise important questions about the power of the social gaze: Who gets to see what? Who decides what is seen or unseen?

These questions are not new, and critics have long raised them with regard to commercial media and journalism. But as the news industry recalibrates, and as wearable devices, smartphones and image/video-sharing platforms proliferate, these questions demand renewed attention. They are, moreover, deeply moral questions of the sort that democracies neglect at their peril.

Unfortunately, the digital economy is still in its adolescence, if not its infancy, and as such it tempts us to act childishly. We have yet to develop appropriate norms, policies and protocols with regard to the use of wearable technologies or the images they record. Our situation is not unlike that of the Kalahari tribespeople in the 1980 film “The Gods Must be Crazy,” whose moral universe was forever disrupted when a thoughtless pilot dropped a Coke bottle from his plane. That strange new thing made a great tool for decorating clothing, but one boy found that it was also great for hitting someone on the head. As the narrator noted, “other new things came: anger, jealously, hate and violence.” But the tribe’s leader quickly found that he couldn’t simply throw the thing back up into the sky.

We like to think of ourselves as technically and culturally advanced, but we often act as if smartphones, webcams and Google Glass had dropped down from the sky to disrupt our moral universe. Dharun Ravi, the roommate of former Rutgers student Tyler Clementi, surely regrets wielding his webcam like a weapon, not unlike the boy with the Coke bottle. The consequences, of course, were more severe: Clementi committed suicide after Ravi used the webcam to spy on him, inviting others to the viewing party. It was an extreme invasion of privacy — a type uniquely afforded by networked digital cameras, wearable or otherwise. With due respect to Sarah Slocum, it was a hate crime worthy of the name. Such, at least, was the verdict from a jury of Ravi’s peers. It matters little that he wielded a different type of camera: Dharun Ravi acted like a Glasshole.

To be clear, I’m not opposed to digital technology in general or wearable gadgets in particular. We can’t throw them back up into the sky, so to speak. But we do face important decisions in terms of design, production, use and regulation. So far, we’ve failed to take these issues seriously. As it stands, we are a nation of Glassholes.

* * *

Let’s get specific. I’m suggesting that the term “Glasshole” warrants much wider application than it has recently enjoyed. In this broader, metaphorical sense, a Glasshole is someone who does one or more of the following:

1) Demonstrates a sense of entitlement to the power afforded by privileged access to digital media technologies and information networks.

2) Rationalizes the privileged use of such technologies, and the disruptions they cause, by appealing to myths of technological neutrality, objectivity, inevitability, or utopianism.

3) Treats the concerns and demands of those impacted by disruptive technologies with dismissiveness, contempt, or disdain.

With this broad definition in mind, there are a few key groups who fit the bill. Consider the three criteria above with regard to the following examples.

First Group: Silicon Valley Executives

Technology executives have a flair for rationalizing their exploitation of user data and treating users’ concerns with contempt. In 1999, Sun Microsystems’ CEO Scott McNealy stated flatly, “You have zero privacy anyway… Get over it.” Ten years later, little had changed. A year before Clementi’s suicide, Google CEO Eric Schmidt suggested, “If you have something that you don’t want anyone to know, maybe you shouldn’t be doing it in the first place.” In perhaps the most egregious example Craig Brittain, a rogue entrepreneur in the “revenge porn” industry,justified his non-consensual release of explicit images as “part of a progressive cause” that would eliminate the “stigma” of public nudity.

More recently, privileged access to user data has sparked a backlash against Facebook and OkCupid. Mark Zuckerberg’s disdain for user concerns had already been cited, including his description of early Facebook users as “dumb fucks” for their willingness to share personal information. Facebook’s attempts to manipulate user sentiment, and its patent allowing lenders to “discriminate against borrowers based on social connections,” have added fuel to the fire.

OkCupid’s Christian Rudder faced a similar backlash after revelations that the company had conducted real-time experiments on users. He voiced no regrets. In fact, in a message addressed to OkCupid’s users, Rudder included an image of a guinea pig on which he had scrawled the word “You.” “Guess what, everybody,” he pronounced, “That’s how websites work.”

Actually, that’s how capitalism works. Google Glass street skirmishes, and Twitter-enabled webcam spying, are micro-level examples of a larger tension between the “Big Data rich” and the “Big Data poor,” to borrow a phrase from scholars dana boyd and Kate Crawford. The former rationalize access to, and exploitation of, data in ways that side-step user concerns. But if users feel violated, it matters little if these tactics might help to serve them with more “relevant” ads for shoes or, as the case may be, a spouse.

The Web could be otherwise. To the extent that developers, users and legislators accept the myth of inevitability, commercial platforms will continue to buttress what I have described as architectures of contempt. In other words, tech executives will continue to act like Glassholes, regardless of whether they wear the device.

Second Group: Opportunists, Political or Otherwise

In recent months, citizens have attempted to harness the power of wearable cameras to turn our collective gaze toward the abuses of law enforcement officers. Those efforts include both hand-held (smartphone) cameras and police body cameras. Unfortunately, the backlash against the #BlackLivesMatter movement demonstrates how racially charged ways of seeing are not necessarily overcome—and may in fact be augmented by—the proliferation of wearable technologies.

The presence of police body cameras is no guarantee of oversight or accountability. Local authorities may refuse to release footage, as happened after a shooting death in Cincinnati. In that case, a lawsuit led by the Associated Press eventually forced release of the video. The ACLU argues additionally that law enforcement could selectively exploit its data sets to target citizens. Rather than using data to find a needle in a haystack (i.e., searching for a known criminal), law enforcement agencies could begin to compile what media scholar Josh Meyrowitz calls “haystacks about needles.” An agency could, for example, opportunistically exploit its reservoir of data (including, but not limited to video footage) to target activists. Despite these possibilities — or perhaps in light of them — many officers have described body cameras as “the future of policing” and “inevitable.”

Commercial news media exacerbates these problems. Rarely in the past several months has news coverage highlighted how discriminatory post-WWII housing policies fed into the crises in Ferguson or Baltimore. To their credit, some news sources like the Washington Post and the New Yorker connected those dots. But most did not, and in any case such after-the-fact coverage cannot make up for the cultural ignorance resulting from decades of journalistic neglect of such issues. Much broadcast coverage gravitated toward the spectacle of protests and riots—highly valuable news hooks, which, in the context of that historical ignorance, only serve to reinforce long-standing racial stereotypes. That problem is further compounded as such footage circulates through online echo-chambers.

Not surprisingly, some have manipulated this media environment for personal advantage, by falsely accusing #BlackLivesMatter activists of violence. In Whitney, Texas, a veteran named Scott Lattin vandalized his own truck and blamed #BlackLivesMatter for the damage. His story was retold on local stations Fox 4 News and KWTX, and circulated through right-wing blogs like Breitbart.com and TheRightScoop.com. With the help of conservative social media, he raised $6,000 through an online GoFundMe campaign before the Whitney Police became suspicious. While in custody, Lattin admitted to vandalizing his own truck. He was arrested on misdemeanor charges for filing a false police report.

Lattin’s hoax, initially a financial success, was an exercise in white privilege. It played directly into the stereotype that whites are honest while blacks are deceptive and violent. Local news media assumed he was telling the truth, and the conservative blogosphere was more than happy to have evidence supporting its narrative that #BlackLivesMatter is not a civil rights group in the spirit of Martin Luther King Jr. but a “hate group.”

Incidentally, these are the same stereotypes that drove coverage of President Obama and his former pastor, Rev. Jeremiah Wright, during the 2008 campaign. Pundits like Sean Hannity portrayed video footage of Wright’s post-9/11 sermons as evidence that Obama’s post-racial rhetoric was merely a mask for his true identity as a black radical. According to the Pew Research Center, the Wright issue became “the single largest press narrative in the campaign, religious or otherwise.” It could have cost Obama the election if John McCain had not forbidden his campaign staff from pressing the issue.

Much like the 2008 campaign against Obama, the backlash against #BlackLivesMatter leverages media access and racial stereotypes to maintain the cultural status quo. The abandonment of truth and accuracy is accepted as collateral damage. Through contemptuous ploys that manipulate what and how the public see, opportunists of Sean Hannity or Scott Lattin’s ilk—not to mention the willfully deceptive editors of those recent Planned Parenthood faux-expose videos—are worthy of the title: they acted like Glassholes.

Third Group: Overzealous Hacktivists

The problem works both ways, ideologically speaking, since it’s relatively easy to leverage out-of-context video to score political points. Footage of George W. Bush playfully flashing his middle finger at a local television cameraman circulated widely for years in left-leaning circles. But the playing field is more dangerous today, as vigilante hacktivists dig up video, audio, and personal data against perceived offenders.

To be sure, there is a certain gut-level satisfaction in seeing the Church of Scientology or the Westboro Baptist Church get doxxed or otherwise hacked. It’s the same type of rush many felt on seeing the video of Iraqi journalist Muntadhar al-Zaidi throwing his shoes at George W. Bush during a 2008 Baghdad press conference. We sympathize, and cheer, when someone who has been wronged lashes out.

But when the urge to lash out usurps the virtues of prudence and judgment, our actions can backfire. As impatience grew in the wake of Michael Brown’s death in Ferguson, hacktivists circulated two police officers’ names—both of which were incorrect. In that case, it’s possible that hacktivists had been nudged by federal agents in an attempt to discredit them. But in other cases it’s clear that hacktivists sometimes act with malicious intent, for example releasing personal e-mails of CEOs or harassing and threatening critics and their families.

Often donning the Guy Fawkes mask, such hacktivists appear as a Jungian trickster figure, playing malicious jokes in a spirited attempt to nudge a slacking culture toward action or understanding. But as Jung himself noted, the trickster’s moral position is precarious. As more experienced hacktivists acknowledge, risky tactics can backfire and undermine a group’s more noble goals. It’s easy to backslide on that slippery slope from vigilante savior to vengeful prankster. The hacktivists most worthy of praise are those who resist the urge to act like a Glasshole.

How Not to Be a Glasshole: A Primer

Wearable gadgets, and digital technologies in general, are powerful tools that disrupt our moral universe. It takes time to translate long-standing social norms—not to mention laws—into rapidly shifting technical environments. To their credit, groups like WikiLeaks and Anonymous appear to be slowly (perhaps stumblingly) building an ethic of online activism, while companies like Google have developed transparency reports to address user concerns about consumer and government surveillance. But too often hacktivist newcomers, dyed-in-the-wool culture warriors, audience-pandering pundits, and would-be tech monopolists have no qualms about side-stepping ethics in pursuit of short-term political and economic victories. Call me old-fashioned, but this is a recipe for disaster no matter whose side you are on.

In the context of the emerging digital economy, the nonviolent philosophy of Martin Luther King Jr. remains relevant and worth translating into today’s technical environments. In his 1961 speech “Love, Law and Civil Disobedience,” King articulated an approach that is based on a basic commitment to human dignity, self-respect, compassion, and hope. In summary, here are the six guiding principles he outlines in that speech:

- The end doesn’t justify the means. The means “must be as pure as the end.”

- Follow “a consistent principle of non-injury” by avoiding both physical violence and “internal violence of spirit.”

- The “ethic of love,” which means understanding and good will for all, must be the foundation of all action.

- Target “the unjust system, rather than individuals who are caught in that system.”

- Accept the suffering that results from your resistance, as it “may serve to transform the social situation.”

- Appeal to the “amazing potential for goodness” that exists in all people.

Consider how each of the groups described above—Silicon Valley executives, opportunists of various stripes, overzealous hacktivists—consistently violate one or more of these foundational principles. In some cases, I would argue, all six of King’s principles are up-ended.

The benefits of ad personalization, or more effective social networking services, do not justify tech executives’ violations of user privacy and basic norms of consent. When terms of service and user policies are written as cryptic tomes intended to protect corporate interests, the spirit of understanding and good will is displaced by architectures of contempt.

By claiming to be victims of hate crimes, gadget geeks and small-time opportunists belittle the history of discrimination in the U.S., and belittle themselves in the process. Whether by law enforcement officials or media pundits, the selective use of data or video footage for ideological or personal gain violates basic norms of professional integrity. Such actions amount to an “internal violence of spirit” that cynically degrades public discourse.

Hackers damage their own campaigns by maliciously targeting individuals rather than unjust systems. Online anonymity contains a temptation toward vengeance that can cause the pursuit of justice to backfire. It is worth noting that King’s civil rights marchers managed to “transform the social situation” by willingly facing jail time (or worse)—not by donning masks.

None of this is to say that wearable gadgets, body cameras, social networks or other digital media are inherently problematic. On the contrary: each holds tremendous potential for revitalizing basic democratic ideals—transparency and accountability in government and business, for example. Research on police body cameras is promising. Wearable cameras have clear potential for use in medicine and other fields.

Technology can augment human dignity and strengthen our hope for the future. By no means should we try to throw these gadgets into the sky, hoping that the gods will reclaim them for our own good. Ironically, we are the gods who (sometimes willfully and sometimes unwittingly) toss the tools of disruption into the hands of our own unready tribe. Which tools we build, who designs them and for what purpose, and how we use and regulate them—these are questions that must not be glossed over by myths of technical beneficence and inevitability. They are questions of morality and ethics, not of engineering. But we have barely begun to address them seriously.

While he could not have anticipated the types of issues we face today, King’s principles provide a framework for that much-needed discussion. The conversation will not be devoid of conflict since, as King himself noted, it requires that we distinguish the “negative peace” of complacency from the “positive peace” that must be earned through collective struggle. Sometimes a hidden camera will justly blow the whistle, and sometimes it will mislead. Sometimes a police body camera will implicate an officer, and sometimes it will exonerate him. But this does not mean that technologies are morally neutral. To the extent that we indulge them, the temptations toward vengeance, opportunism, and privilege afforded by digital technologies will detract from the universal human drive toward dignity. Until such time as we embrace non-violent principles in every aspect of technical development—design, fabrication, regulation and use—we will continue to be a nation of Glassholes.