Documentarian Chris Whipple has some new bombshell revelations about how the Bush administration ignored the advance warnings of 9/11 in story for Politico, “‘The Attacks Will Be Spectacular,’” a spin-off of his documentary, "The Spymasters," set to air this month on Showtime, in which he interviews all 12 living former CIA directors.

Whipple’s most stunning revelations revolve around a July 10 meeting that’s been mentioned by others in books before—Bob Woodward, George Tenet, Condi Rice—but always in a manner that drastically underplays the urgency of CIA’s warnings, and how much they had to go on, according to Whipple’s new information:

By May of 2001, says Cofer Black, then chief of the CIA’s counterterrorism center, “it was very evident that we were going to be struck, we were gonna be struck hard and lots of Americans were going to die.” “There were real plots being manifested,” Cofer’s former boss, George Tenet, told me in his first interview in eight years. “The world felt like it was on the edge of eruption. In this time period of June and July, the threat continues to rise. Terrorists were disappearing [as if in hiding, in preparation for an attack]. Camps were closing. Threat reportings on the rise.”

Finally, things boiled over:

That morning of July 10, the head of the agency’s Al Qaeda unit, Richard Blee, burst into Black’s office. “And he says, ‘Chief, this is it. Roof's fallen in,’” recounts Black. “The information that we had compiled was absolutely compelling. It was multiple-sourced. And it was sort of the last straw.”

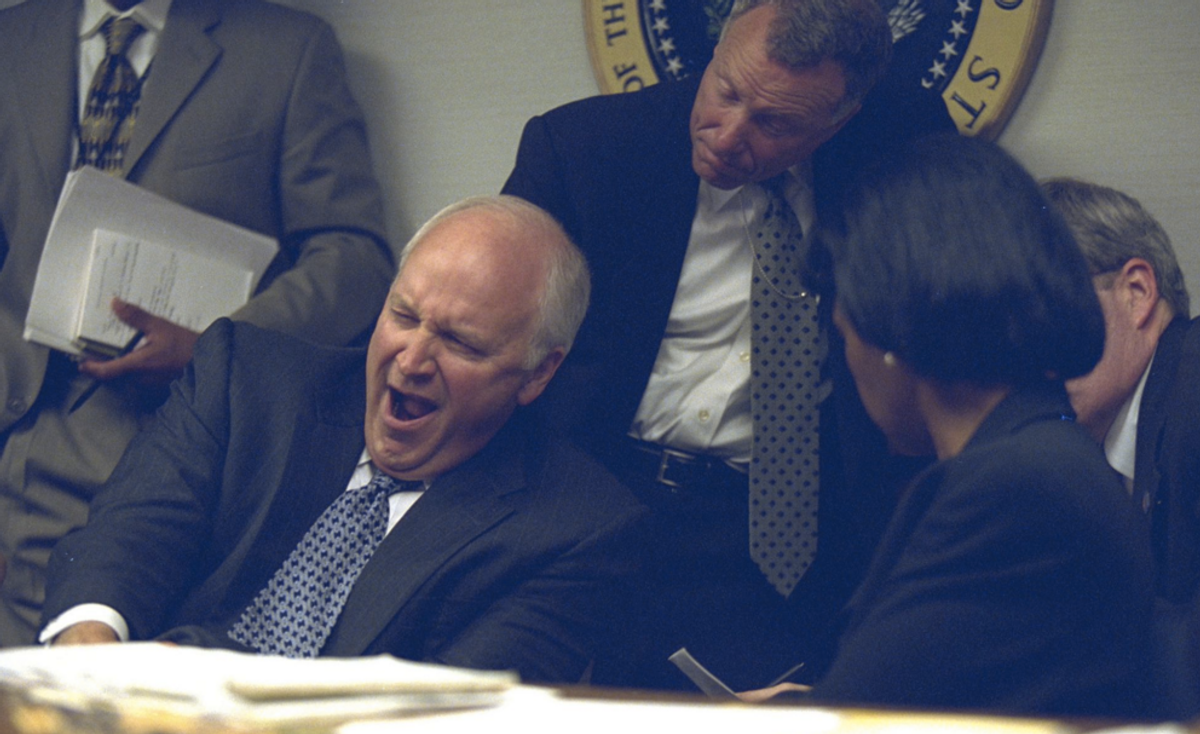

Tenet called Rice for an immediate meeting with her and her team—Bush was out of town:

“Rich [Blee] started by saying, ‘There will be significant terrorist attacks against the United States in the coming weeks or months. The attacks will be spectacular. They may be multiple. Al Qaeda's intention is the destruction of the United States.’" [Condi said:] ‘What do you think we need to do?’ Black responded by slamming his fist on the table, and saying, ‘We need to go on a wartime footing now!’”

But nothing happened. “To me it remains incomprehensible still,” Black told Whipple. “I mean, how is it that you could warn senior people so many times and nothing actually happened? It’s kind of like The Twilight Zone.”

Tellingly, Condi Rice has no clear recollection of the meeting. For her, it was all a blur. As Whipple quotes from her memoir, “My recollection of the meeting is not very crisp because we were discussing the threat every day.” But no one could have foreseen it?

It was not just a failure to respond to warnings, however. There was a broader refusal to even consider thinking proactively. Along these lines, Whipple writes more broadly about Tenet and Black’s plan to “end the al Qaeda threat” with a combined military/CIA campaign “getting into the Afghan sanctuary, launching a paramilitary operation, creating a bridge with Uzbekistan.” They pitched the plan in spring of 2001, according to Whipple, “‘And the word back,’ says Tenet, ‘was “we’re not quite ready to consider this. We don’t want the clock to start ticking.”’ (Translation: they did not want a paper trail to show that they’d been warned.)”

Black chalks this up to the Bush team being stuck in the past, thinking of terrorists as “Euro-lefties,” but there was a deeper story, with more to the state of denial than Whipple discusses, since the Bush team was also actively fending off dealing with the recommendations of bipartisan Hart-Rudman Commission (officially the “U.S. Commission on National Security/21st Century”). It had warned that “Americans will likely die on American soil, possibly in large numbers."

Hart-Rudman released a series of three reports, first an overview of the challenges, “New World Coming: American Security in the 21st Century,” released in September 1999, then a strategy report, “Seeking a National Strategy: A Concert for Preserving Security and Promoting Freedom,” released in April 2000, and finally, a recommendation report, “Roadmap for National Security: Imperative for Change,” released at the end of January 2001, just after Bush took office. Not only did Hart-Rudman see terrorist attacks as a possibility, it highlighted five key areas for reform, the first of which was “ensuring the security of the American homeland.” It regarded a 9/11-style attack as so likely that defending against it should be a top priority in rethinking our entire approach to national security.

Congress members were interested in holding hearings on the commission findings, but the Bush administration discouraged them. As Molly Ivins later recalled:

Of the various institutions, Congress deserves some credit for trying to pick up on the report, which clearly would have moved us ahead by six months on terrorism planning.

Donald Rumsfeld, not one of my favorites, also deserves credit for vigorously backing the report. Congress scheduled hearing for May 7, 2001, but according to reports at the time, the White House stifled the move because it did not want Congress out in front on the issue.

“remember, EIGHT Benghazi investigations yet Bush WH sat on its hands while bin Laden got ready to kill 3K Americans,” Media Matters’ Eric Boehlert tweeted. “if this story were abt Benghazi, GOP would introduce Obama impeachment proceedings today,” he followed up. Boehlert’s point is obviously valid, but even more troubling is how the lack of accountability has made things so much worse, actually crippling our ability to win the war on terror.

The failure to hold anyone accountable for 9/11 is inextricably intertwined with the broader failure to go back and rethink fundamental questions on all aspects of national security—something that was obviously needed at the time, and that remains imperative still. The Hart-Rudman Commission was an effort to do that, albeit an imperfect one. It was the first such broad-ranging review since the early Cold War, yet it made no real attempt to make sense of what had worked and (most important) what hadn’t across all those decades. It did try to grapple with how threats were changing, however, and it defined the question of national security quite broadly. Hence, the second area identified for fundamental reform was “recapitalizing America's strengths in science and education.”

What 9/11 should have done was inspire a much more sweeping, much more thorough rethinking of what national security means in the 21st century, and how to maintain it. Instead, the knee-jerk defensiveness of the Bush administration short-circuited everything we needed to do in the way of rethinking, leaving a host of unanswered questions that bedevil us still, and cripple our ability to even understand how we can make the world a safer place. Regrettably, the Obama administration has never had the stomach to take up what Bush ran away from.

Whipple reports that the former CIA chiefs remain divided over torture, troubled by their muddled role in drone assassinations, and confused over the agency's mission "Is it a spy agency? Or a secret army?" The paramilitary focus on immediate action not only undermines the intelligence function, it undermines the war on terror itself. “An awful lot of what we now call analysis in the American intelligence community is really targeting,” Michael Hayden told Whipple. “Frankly, that has been at the expense of the broader, more global view.”

The CIA focus on winning battles may actually be losing the war, as even Hayden seems willing to admit, though there’s never been a national debate about what to do instead. “Some of the things we do to keep us safe for the close fight—for instance, targeted killings—can make it more difficult to resolve the deep fight, the ideological fight,” he said. “We feed the jihadi recruitment video that these Americans are heartless killers.”

The dilemma is clear; we are “winning” by losing:

Who’s winning? The CIA—or radical Islam? “The big picture,” says Morell, the two-time acting director, “is a great victory for us and a great victory for them. Our great victory has been the degradation, decimation, near-defeat of the Al Qaeda core that brought tragedy to our shores on 9/11. But their great victory has been the spread of their ideology across a huge geographic area. What we haven’t done a good job of is stopping new terrorists from being created. And until we get our arms around that, this war is not going away.”

In fact, it’s only getting much, much worse. Until we’re finally ready to rethink everything we think we know.

Shares