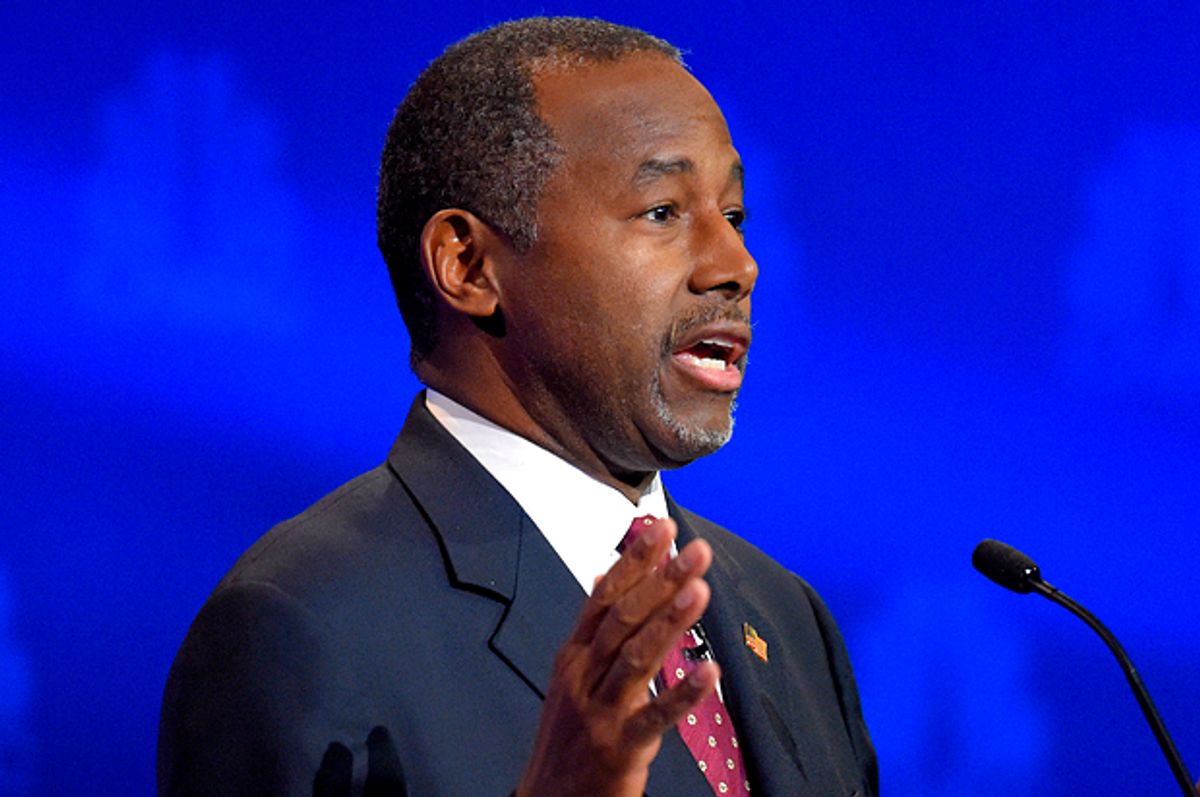

For months now, Ben Carson has been rising in the polls, but as long as the far more flamboyant Donald Trump was ahead of him, the chaos engendered by Trump focused almost all attention around him. Last week, all that changed as Carson clearly emerged to top Trump, and finally started getting a level of attention and scrutiny he's warranted for some time. It has not been pretty.

No one doubts the core truth of Carson's Horatio Alger narrative—a child of the underclass who became a world-renowned neurosurgeon. But that only makes the surrounding, objectively unnecessary lies all the more puzzling to many. Why lie about having been a violent youth—even stabbing someone—when no one else remembers him that way? Why lie about being offered a full West Point scholarship, when no such thing exists, and he went to Yale anyway? And when such questions are raised, why complain that “I do not remember this level of scrutiny for one President Barack Obama,” when, as Bill Moyers noted on April 25, 2008, “More than 3,000 news stories have been penned since early April about Jeremiah Wright and Barack Obama.”

As Kevin Drum explains, one reason Carson tells “unnecessary lies” is that for his evangelical base, they're anything but unnecessary, they're essential:

Serious evangelicals really, really want to hear a story about sin and redemption. That requires two things. First, Carson needs to have been a bad kid. Second, redemption needs to have truly turned his life around.

Which is the purpose of anecdotes such as his story about a professor giving him $10 when he was flat broke for being “the most honest student in the class" of 150 students—a story that now appears was based on a humor magazine's hoax. If such stories sound wildly implausible, well, they are—and that's a feature, not a bug:

No one who's not an evangelical Christian would believe it for a second. But evangelicals hear testimonies like this all the time. They expect testimonies like this, and the more improbable the better. So Carson gives them one. It's clumsy because he's not very good at inventing this kind of thing, but that doesn't matter much.

Indeed, Carson's clumsiness readily gets reinterpreted as “authenticity.”

But there's another suspect aspect of the Carson candidacy that deserves much more scrutiny: his role as the “some of my best friends are black” candidate, to help cover for the GOP's unrelenting racial hostility, as the nation grows more diverse, and the GOP grows increasingly antagonistic. Black commentators like Christopher Parker see this in terms of tokenism. Carson is “way too far out of his depth to be taken seriously as a political leader,” he writes, citing some of Carson's wilder claims. “By serving as tokens, Carson and other black Republican candidates allow racist whites to continue to hide from their racism,” he argues, and in the end:

By continuing to represent the GOP as a black man who is patently unqualified, his candidacy does more to perpetuate racism than undo it. His political incompetence is on public display for all to see.

It’s very much akin to a show in which black performers were complicit in their own degradation. And since blacks are almost never afforded the opportunity to be seen as individuals, the humiliation is often extended to blacks as a group.

But, of course, Carson's evangelical base does not see him as a political incompetent. Parker's sense of humiliation as a black professional is valid and real. But something more complicated is going on. The tokenism charge is accurate, but tokenism takes on many different forms, and since it overwhelmingly serves white needs, it helps to pay attention to the white side of the story, which, after all, is where Carson's political appeal lies. White supremacy, after all, is overwhelmingly a white problem. Funny how hard that is to remember.

When I was kid in the late 1950s, first encountering racial politics, I was exposed to two types of racists: those who proudly despised blacks, and those invariably prefaced their racist attitudes with the words, “Some of my best friends are negroes, but....” Given that I lived in Northern California communities with almost no blacks for miles around, it wasn't just my gut telling me that adults saying that had no such black friends, and every word they said was probably a lie—a fairly transparent one. I figured that deep down, they were every bit as racist as those who freely used the N-word, they just felt compelled to hide it—more from themselves than from anyone else.

I can't help but see the same sort of dynamic at work bolstering Ben Carson's candidacy today. After all, the primary purpose of imaginary black friends is to help defend against imaginary black devils, and for most of the GOP base, there has never been an imaginary black devil quite like President Obama, who has now become the very embodiment of the Democratic Party. It's no accident, then, that Carson first gained national attention for rudely attacking Obama directly at the National Prayer Breakfast, an explicitly non-partisan event where politics are supposed to be completely set aside. The Wall Street Journal immediately proposed him for president, and now the right-wing masses have followed suit.

But my take here is not just based on my own particular childhood experience. First, the notion that “some of my best friends are black,” or Jews, or gay, or whatever proves anything at all has long been a subject of ridicule. After all, George Zimmerman had a black friend who vouched for him, and four years ago the New Republic published a brief history of the defense, and how it's been mocked. It included mention of John Roach Straton, the Baptist preacher who popularized the notion that Al Smith, the 1928 Democratic presidential nominee, was “the candidate of rum, Romanism, and rebellion,” but who subsequently told the AP, “Understand I am not a foe of the Catholics. Some of my dearest friends are Catholic.” So, there's nothing new, unusual or idiosyncratic about my reaction to this particular lie.

Second, the whole history of white supremacy in America is shot through with numerous examples of similar face-saving strategies, whenever the core logic gets too ugly to be defended without apology. Any time blacks advance their own leadership, white supremacists look for black allies to substitute for them—allies they can claim as bosom buddies, who fully endorse their anti-black politics. When there were slave rebellions, it was docile, relatively privileged house slaves who were turned to, which helps explain why so many plantation owners felt betrayed after the Civil War, when freed slaves abandoned their plantations in droves—including those many slaveowners claimed were “like part of the family.”

During the civil rights and black power era, the relentless hostility toward black leadership was paired with attempts to prop up alternative “representatives” to strike deals with. In fact, a crucial part of the behind-the-scenes work in desegregating Birmingham, for example, consisted of countering such efforts to split the black community. It took many months to lay the groundwork for the necessary unity, and even then that unity was sorely tested in the battle. Indeed, Martin Luther King's famous “Letter From Birmingham Jail” was written in response to a public letter from eight local clergymen who called the demonstrations he led “unwise and untimely,” and went on to say, “We agree rather with certain local Negro leadership which has called for honest and open negotiation of racial issues in our area.”

With this in mind, there's little surprising in how Republicans have reacted to Barack Obama, going back to when he first ran for U.S. Senate, in 2004. Obama won the Democratic primary with a clear majority, 52.8 percent, more than double the second place candidate, while the Republican candidate, Jack Ryan, won the GOP primary with just 35.5 percent, ahead of two other strong contenders in the 20s. Yet, when Ryan unexpectedly dropped out for personal reasons (the release of divorce proceedings alleging he had taken his wife to public sex clubs), the state party leaders ignored both of them, and instead took six weeks of precious campaign time to select and secure Alan Keyes, a carpetbagger from Maryland, for no other apparent reason than that he was black, and would attack Obama in an all-out manner that no white candidate would dream of doing in the 21st century. As the L.A. Times reported:

Desperate to find someone to compete against Harvard-educated Obama, the Republicans "needed to find another Harvard-educated African American who had some experience on the national political scene," said Republican state Sen. Steven J. Rauschenberger. "We need that because the Democrats have made an icon out of Barack Obama. The only way to fight back is to find your own icon, and that is not an easy thing to do."

Like Carson, and Herman Cain (Remember him? 9-9-9?), Keyes had no experience in elected office—though, in his case, not for lack of trying. The Times noted that Keyes had lost badly in two previous Senate runs in Maryland. "In 1988, he got 38% of the vote; in 1992, he got 29%." Some icon! But he had managed to make a decent career out of being a black conservative, as have many others as well. In fact, the Times reported:

In 1992, Keyes was criticized for using campaign funds to pay himself a monthly salary of $8,500 -- an unusual, though legal, strategy at the time.

Illinois GOP officials said that Keyes had assured them he wouldn't do that during this campaign.

Not only was Keyes a carpetbagger, he was a carpetbagger with a record of denouncing carpetbagging. When Hillary Clinton first ran for Senate in New York, Keyes said, "I deeply resent the destruction of federalism represented by Hillary Clinton's willingness to go into a state she doesn't even live in and pretend to represent the people there. So I certainly wouldn't imitate it."

What Keyes did have (foreshadowing Carson) was a religious conservative message—and the claim that he, not Obama, represented the authentic African-American experience, since Obama's ancestors hadn't been slaves. "Barack Obama claims an African American heritage, yet stands against the very things that were the basis for [stopping] the oppression of my ancestors," Keyes told George Stephanopoulos, going all-in on the religious right effort to equate abortion with slavery—a popular position among white evangelicals, that tends to make many black religious conservatives a good deal more uneasy, just as religiously conservative Jews tend to denounce, not embrace, antiabortion "holocaust" rhetoric.

Carson entertains some of the same confluence of attitudes. His notorious claim that Obamacare “is slavery, in a way” appears to be partially rooted in the same sense that he, Carson, is the authentic African-American, descended from slaves, instinctively freedom-loving, as opposed to Obama, who is an imposter, an interloper—which ties in with birtherism as well. This isn't to claim that Carson himself is a birther, only that his questioning of Obama's authenticity synergizes with that coming from the broader, white right-wing base.

Similarly, a white conservative casually equating Obamacare with slavery would be savagely condemned in a way that Carson was spared, simply because he is black. There is a back-and-forth exchange of “likely stories” that facilitates the creation of an elaborate shared fantasy, in which, among other things, all the outrageous things Carson says are true, and white conservatives defending him prove that liberals, Democrats and the vast majority of blacks are the “real racists” after all. And if Carson can help them to really believe that fantasy, well, maybe he really is one of their best friends after all.

At least that's what today's GOP would like to believe.

Shares