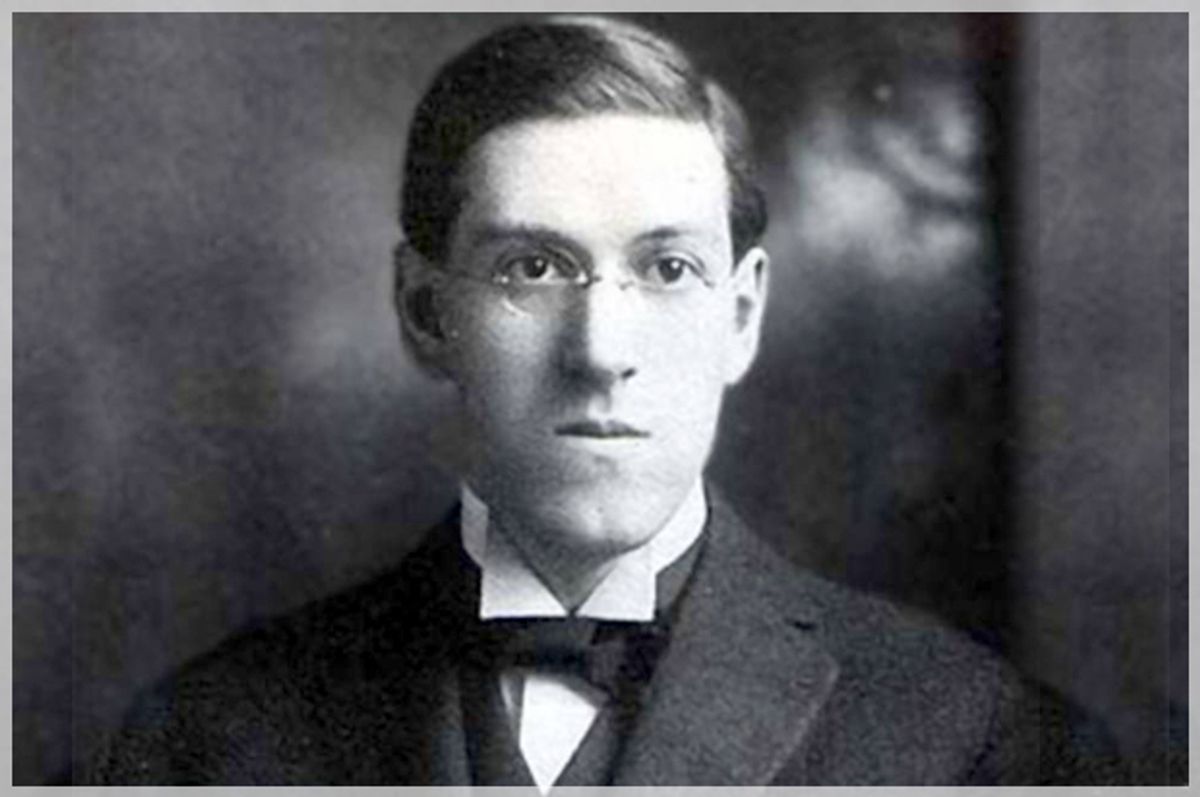

Howard Phillips Lovecraft will make you believe in ghosts.

The legendary “cosmic horror” author has been dead for 78 years, and yet he continues to get more controversial by the day.

The most recent flare-up began on November 8, in Saratoga Springs, New York, when organizers of the World Fantasy Convention announced that, after forty years, Lovecraft’s face will no longer appear on the World Fantasy Award trophy. 2015 is the last time writers will win a “Howard,” as the award is known.

Now if you’re just arriving to this conversation, there are two main things you need to know. First, Lovecraft – who wrote “The Call of Cthulhu,” “The Colour Out of Space” and other influential tales of madness and “sentient blob[s] of self-shaping gelatinous flesh” – is one of weird fiction’s most celebrated authors. He is enshrined in the Library of America. Stephen King calls him “the twentieth century's greatest practitioner of the classic horror tale.” The author of the novel "Psycho," Robert Bloch, once wrote, “Poe and Lovecraft are our two American geniuses of fantasy, comparable each to the other, but incomparably superior to all the rest who follow.”

Second, as Lovecraft’s letters – and, to a lesser extent, his stories – reveal, the guy harbored a fierce loathing for almost all non-WASPs. Blacks were “greasy chimpanzees,” in Lovecraft’s words. French-Canadians were a “clamorous plague.” New York’s Chinatown was “a bastard mess of stewing mongrel flesh.” And so on.

The tension between these two truths has gnawed at the World Fantasy Awards for years. In 2011, WFA-award-winning writer Nnedi Okorafor wrote a blog post ruminating on Lovecraft’s infamous poem “On the Creation of N***ers” and what it means to receive an honor bearing the author’s likeness. Last year, the Brooklyn-based writer Daniel Jose Older launched a petition demanding the WFA statuette be changed. When news of WFC’s decision broke, Older tweeted “WE DID IT. YOU DID IT. IT'S DONE. YESSSSSSSS.”

Not everyone was as thrilled. On his blog, Lovecraft biographer S.T. Joshi described the removal as a “ridiculous” move “meant to placate the shrill whining of a handful of social justice warriors.” He included a letter he’d written to the WFC board co-chair announcing he would return his WFA trophies and do “everything in my power to urge a boycott of the World Fantasy Convention among my many friends and colleagues.”

A much creepier response came from the “white nationalist” site counter-currents.com, which reminded readers of its recently-launched “H. P. Lovecraft Prize for Literature, to be awarded to literary artists of the highest caliber who transgress the boundaries of political correctness…[a]s the Left continues to hollow out and destroy institutions, corrupt minds and culture, and denigrate white greatness.” In the words of fantasy/sci-fi/horror writer Scott Edelman: “Whoa.”

Now, there’s no quick answer to the question of how, exactly, we ought to approach a man talented enough to be the “King of Weird” and bigoted enough to casually describe his genocidal urges. (Lovecraft, on Jews: “I’ve easily felt able to slaughter a score or two when jammed in a N.Y. subway train.”) The conversation will – and should – continue long after this article.

But I do have a practical answer for the question of what to do with rejected or discarded “Howard” trophies: Send them to Providence, Rhode Island. Providence – founded in 1636; 2010 population: 178,038 – was Lovecraft’s hometown, and it’s where I’m currently teaching a semester-long class on the author at the Rhode Island School of Design. And no object better embodies the complexity of his legacy than these now-outdated trophies. They are the perfect teaching tool.

After all, Providence plays a major role in the Lovecraft story. It’s where he spent all but a couple years of his life. It’s a playground for the slithering, malevolent creatures he imagined. (See “The Shunned House” and “The Haunter of the Dark.”) And it’s a place that he loved with such fervency that he once declared in a letter “I Am Providence” – a quote now etched on his tombstone, in the city’s Swan Point Cemetery.

Lovecraft’s racial views are not irrelevant to his civic pride. In one letter, he wrote “New England is by far the best place for a white man to live.” In another, he added, “America has lost New York to the mongrels, but the sun shines just as brightly over Providence.”

For decades after his death, Lovecraft’s hometown love was mostly unrequited. But recent years have brought a long-delayed love-fest. Drive through Providence today and you’ll see “H.P. Lovecraft Memorial Square,” two plaques in his honor, and a Lovecraft bust in the city’s famed Athenaeum library. The city has Lovecraft-themed read-a-thons, walking tours, research fellowships, apps, writing contests, and bars that serve Lovecraft-inspired drinks like the “Bittersweet Tears of Cthulhu” and “Lovecraft’s Lament.”

On Halloween, at the recently opened “Lovecraft Arts & Sciences Council” store, I read an essay arguing that Lovecraft is now our city’s most famous citizen, past or present. And, in a sense, this is fitting – not despite the thorniness of his legacy, but because of it.

The 379-year-old saga of Providence swerves frequently from vice to virtue, achievement to embarrassment. Yes, we basically invented religious freedom, but we also headquartered the New England mafia. Yes, we once made everything from silverware to steam engines, but more recently, we’re known for the spectacular implosion of Curt Schilling’s publicly subsidized video game company.

Often the city’s contradictions are found in the same place. In the late 18th century, the Brown family – which included the abolitionist, Moses, and his slave-trading brother, John – was torn in two by the traffic of human beings, as the author Charles Rappleye illustrates in his award-winning book, "Sons of Providence: The Brown Brothers, the Slave Trade, and the American Revolution."

(A 2006 report confirms that Brown University’s signature building was constructed, in part, by slave labor.)

Centuries later, when Providence woke from its post-industrial coma with a much touted 1990s/2000s “renaissance,” the man who led the resurrection – the charismatic, yet violent and vengeful, mayor Vincent “Buddy” Cianci – was convicted of running the city as a criminal enterprise. “'I'm struck between the parallels between this case and the classic story of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde,'' a federal judge told Cianci in 2002, before sentencing him to prison.

And then there’s Lovecraft: our homegrown “Literary Copernicus” and outspoken white supremacist. The same guy who gave us the Internet’s favorite tentacled monster, Cthulhu, once wrote to a friend, “The only thing that makes life endurable where blacks abound is the Jim Crow principle, & I wish they’d apply it in N.Y. both to niggers & to the more Asiatic type of puffy, rat-faced Jew.”

(Both Cthulhu and that quote appear in a new Keith Knight political cartoon captioned “H.P. Hatecraft.”)

This unresolved – perhaps unresolvable – tension is exactly what an exhibit of discarded “Howard” trophies would emphasize. I haven’t figured out where, exactly, it would be. Maybe Brown University’s Lovecraft Collection? But I will suggest some readings to accompany the show.

It would be wise to include some of S.T. Joshi’s arguments against Lovecraft-pushback, like the June 2014 blog post in which he argues, “In the totality of Lovecraft’s surviving letters, I would be surprised if racial issues are addressed in more than 5 percent of the text—perhaps no more than 1 percent…[and] There are perhaps only five stories in Lovecraft’s entire corpus of 65 original tales (‘The Street’ ‘Arthur Jermyn,’ ‘The Horror at Red Hook,’ ‘He,’ and ‘The Shadow over Innsmouth’) that have racism as their central core.”

But there should also be testimonials from WFA-winning writers like Sofia Samatar, who, after winning a “Best Novel” WFA last year, wrote, “Everyone should be able to announce their awards with unadulterated joy! And unless the statue is changed, there will be a lot more posts like this.”

And of course we’d need some primary-source material from the man, himself. Lovecraft’s descriptions of Providence in the novella “The Case of Charles Dexter Ward” are some one of the most lyrical passages every written about the city. And yet he penned some of the most alarming passages, too.

Once, during an ill-fated stint living in New York City, Lovecraft described the horror of a trip to the Bronx where he encountered crowds where “nine of every ten [were] flabby, pungent, grinning, chattering n***ers!”

“Wilted by the sight,” he wrote, “we did no more than take a side path to the shore and back and reenter the subway for the long homeward ride – waiting to find a train not too reminiscent of the packed hold of one of John Brown’s Providence merchantmen on the middle passage from the Guinea coast to Antigua or the Barbadoes.”

Riffs like this make you wonder: what did Lovecraft mean when he wrote, “I Am Providence,” anyway?

Shares