“Politicians, like generals, have a tendency to fight the last war.” — John Bolton

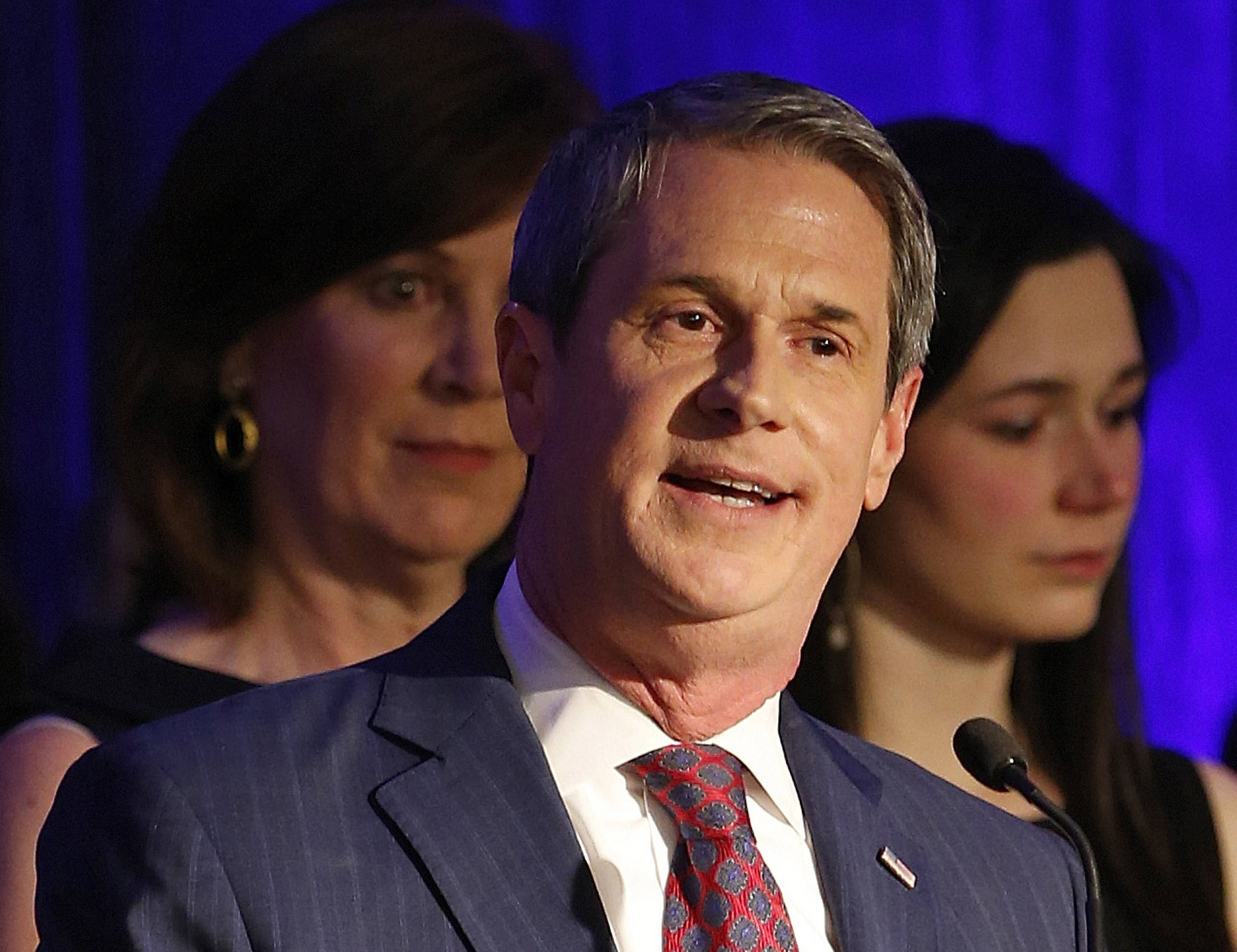

Perhaps it was latent disgust at U.S. Sen. David Vitter’s 2007 prostitution scandal. Maybe his vicious attacks against his Republican opponents backfired and split the Louisiana GOP. Perhaps Vitter finally ran up against a potent, well-funded Democratic opponent at exactly the wrong time.

The pundits will offer these and other plausible theories about how Louisiana Democratic Gov.-elect John Bel Edwards defied enormous odds in Saturday’s election and vanquished Vitter, a Republican and the once-prohibitive favorite.

Each theory is probably valid and a piece of the crazy puzzle that resulted in Edwards’ improbable victory. My analysis, however, is simple. It’s about how Vitter and his aides incorrectly analyzed the race more than a year ago.

I believe that Vitter lost to Edwards for the same reason the United States lost the Vietnam War to Ho Chi Minh’s Viet Cong. Like the hapless U.S. generals and their Pentagon bosses in the 1960s, Vitter made several fatal miscalculations: First, he underestimated and misunderstood his opponent. And he fought with once-successful, but now-outdated, strategies from previous campaigns. (Full disclosure: Last spring, I would not have disputed Vitter’s strategy. In fact, I wrote that it would probably work.)

In his book On War, the Prussian general and military theorist Carl von Clausewitz observed that the “first, the supreme, the most far-reaching act of judgment that the statesman and commander have to make is to establish . . . the kind of war on which they are embarking; neither mistaking it for, nor trying to turn it into, something that is alien to its true nature. This is the first of all strategic questions and the most comprehensive.”

Most Vietnam War historians agree that the U.S. military ignored Clausewitz’s wisdom. We badly misjudged the Vietcong, underestimated its strength and tenacity and misinterpreted the very nature of the war we were fighting. The U.S. confronted a well-armed insurgency with a conventional strategy of conquering and holding territory. Put simply, our generals employed World War II and Korean War-style tactics to fight an insurgency in South Vietnam that was not about territory but hearts and minds.

We lost because we did not know what kind of war we were fighting.

Clausewitz’s advice on war applies to politics, as well. Vitter did not know what kind of campaign he was running. In fighting his Democratic opponent, he made the same mistakes as the U.S. generals in Vietnam 50 years ago. He did not adapt to new circumstances. Simply put, Vitter fought “the last war.”

Based on earlier, successful campaigns, Vitter assumed he would easily win so long as he faced a Democrat in Saturday’s runoff (Louisiana has an open election system in which Democrats and Republicans are on the same ballot in a non-partisan primary). As he hoped, Vitter got Edwards as his runoff opponent, after he savagely attacked and eliminated his two Republican opponents.

Vitter’s experience told him that from there, victory was a simple matter of raising as much money as possible and using it to run spots attacking Edwards as an Obama clone. As he had done in the past, Vitter planned to make the election a simple referendum on Obama. Based upon his easy victory in 2010, Vitter also likely assumed that his prostitution scandal was no longer an issue.

If that’s what Vitter thought about this governor’s race (and all the available evidence suggests that he did), he badly miscalculated.

Hard as he tried this election, he never made the race about Obama. Instead, to his dismay, the campaign became a referendum on Vitter – his judgment, ethics and character. The prostitution scandal that Vitter assumed was resolved became, instead, a central theme of the race.

At every turn, Vitter’s assumptions about the race proved incorrect. Relying on experience – fighting the only way he knew – Vitter waged the wrong war, using the wrong strategy and the wrong tactics.

In his 2010 re-election against then-Democratic U.S. Rep. Charlie Melancon, Vitter masterfully turned the race into a referendum on President Obama, negating any damage from his prostitution scandal. In that race, Vitter ran several effective TV spots that turned Melancon into an Obama proxy.

That year, Vitter also aired an ugly, racist TV spot that attacked Melancon and vilified illegal aliens (he showed swarthy Mexican-looking men climbing through a fence and running toward a waiting limousine).

Vitter’s scorched-earth style worked. He won with 56.6 percent of the vote.

Last year, in a race managed by Vitter’s communications director, then-Republican U.S. Rep. Bill Cassidy handily defeated Sen. Mary Landrieu using the same playbook. Cassidy didn’t even need complete sentences to tie Landrieu to Obama. He said, simply, “Landrieu. Obama. 97 percent.” (In other words, Landrieu voted with Obama 97 percent of the time.) The attacks were effective and deadly. After three terms in the Senate, the more liberal Landrieu was a plausible proxy for Obama in the eyes of Louisiana voters. She never stood a chance against Cassidy.

Edwards, to Vitter’s complete surprise, was not so vulnerable.

Relying on his 2010 success, this year Vitter launched his runoff campaign in late October with a racist, Willie Horton-like spot that tried to tie Edwards to Obama’s plan to release 6,000 federal inmates jailed for non-violent crimes.

In the spot, photos of Obama and Edwards were juxtaposed as the announcer warned, “Voting for Edwards is like voting to make Obama Louisiana’s next governor. Want proof? Obama dangerously calls for releasing six thousand criminals from jail. Edwards joined Obama, promising at Southern University he’ll release fifty-five hundred in Louisiana alone,” the spot continued. “Fifty-five hundred dangerous thugs, drug dealers, back into our streets.”

The spot not only exposed Vitter as a panderer to racists, but it also didn’t work. Edwards’ lead in the polls grew in the days after the spot began airing.

Vitter wrongly assumed that simply because Edwards is a Democrat, tying him to Obama would be easy. What Vitter forgot, however, was that Edwards was no Washington politician (he has served in the state House for the past eight years).

Edwards is conservative. He’s pro-life, pro-gun and opposed to Common Core. Most important, Edwards is a West Point graduate, former Army Ranger and the grandson, son and brother of Louisiana sheriffs. In almost every way, Edwards was unassailable. In a race that unexpectedly turned on character (not ideology and policy, as Vitter anticipated), Edwards proved almost unbeatable.

Based on his effortless win in 2010, Vitter also wrongly assumed his prostitution scandal wouldn’t emerge in a way that would harm him. Perhaps he never counted on several super PACs raising significant sums to air spots reminding voters of what Vitter once called his “serious sin.” He probably also didn’t count on strong, effective attacks about prostitution coming from his Republican opponents and, in the runoff, from Edwards.

Vitter’s two Republican opponents, and several super PACs, attacked Vitter ruthlessly in the primary over the prostitution scandal. That took a toll, which is one reason Vitter received only 23 percent of the primary vote, compared to Edwards’ 40 percent. After Edwards ran a devastating spot in early November, suggesting that Vitter had missed a House vote in 2001 honoring fallen soldiers) while waiting on a call from a prostitute, the 2007 scandal was no longer old news. It suddenly became the election’s centerpiece.

Like Gen. William Westmoreland in Vietnam, Vitter badly misjudged the battlefield. He thought he commanded the high ground. Instead, Edwards occupied the more defensible terrain.

Vitter did not realize, until it was too late, that Louisiana voters have higher standards for who they elect as governor, compared to who they send to Washington. A West Point graduate and Army Ranger versus a prickly, career D.C. politician stained by a sex scandal? For many voters, the choice was not difficult.

In retrospect, Vitter is undoubtedly wishing he had held a press conference early in 2015 and invited journalists to ask him (and, possibly, his wife) every possible question about his prostitution scandal. It would have cleared the air and maybe put the scandal to rest.

If Vitter had anticipated his opponents’ attacks, instead of looking at the race through the lens of 2010, he might have blunted or negated them early. If he had those answered questions last year, attacks on him in the fall might have looked personal and cruel. They might have generated sympathy for Vitter.

Instead, by the time Vitter began running various apology spots late in the campaign, they only served to remind voters of questions he had never adequately addressed or answered. He looked defensive and desperate.

In his treatise on warfare, Sun Tzu wrote, “If you know the enemy and know yourself, you need not fear the result of a hundred battles. If you know yourself but not the enemy, for every victory gained you will also suffer a defeat. If you know neither the enemy nor yourself, you will succumb in every battle.”

Vitter once knew himself and his enemy, which is why he won a smashing victory in 2010 just three years after his prostitution scandal almost destroyed his political career. How ironic that concerns about his character – eight years old and thoroughly vetted by voters in a major election – brought him down on Saturday night.

It might have been different had Vitter known as much about military strategy as he did the game of politics. It is either ironic, or perhaps profound poetic justice, that in badly misjudging his enemy, Vitter was destroyed by a West Point graduate – a man well schooled in the art of war.