Bernie Sanders has made a pledge to abolish private prisons in the federal system a centerpiece of his criminal justice reform platform, expounding on it in speeches, tweets and a bill that he introduced in the Senate. “The profit motivation of private companies running prisons works at cross purposes with the goals of criminal justice,” Sanders said, according to USA Today. “Criminal justice and public safety are without a doubt the responsibility of the citizens of our country, not private corporations. They should be carried out by those who answer to voters, not those who answer to investors.”

What people, including Sanders, don’t mention about the bill is that it does something far more radical as well: It would reestablish federal parole, the abolition of which three decades ago was a key ingredient in fueling the explosive growth of the American prison system.

Two key factors have driven prison population growth since the 1980s. One is the length of sentences, which where were increased by measures like the passage of harsh mandatory minimums for drug offenses and tough sentencing guidelines imposed on judges. Another is the percentage of those sentences that a prisoner actually serves, which the abolition of parole greatly extended. Inmates would thenceforth serve the near entirety of their sentence—a so-called determinate sentence—aside from a maximum of 15-percent reduced for good behavior.

Parole eligibility was abolished for all those convicted of committing a federal crime on or after November 1, 1987 as a result of the Sentencing Reform Act of 1984. The impact was swift and severe. Those entering prison in 1996 could expect to serve 87 percent of their sentences behind bars, compared with 58 percent a decade earlier,” according to a study by The Pew Charitable Trusts.

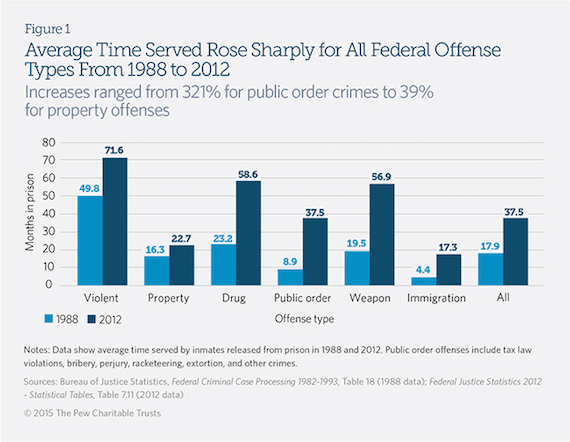

Mandatory minimums and determinate sentences combined drove the average time federal inmate served behind bars, which rose from 17.9 months in 1988 to 37.5 months in 2012, according Pew. During that time period, the federal prison population rose from 49,928 inmates to 217,815.

(Chart courtesy of The Pew Charitable Trusts.)

Today, the possibility of parole only exists for a vanishingly small portion of federal inmates—3 percent, according to a 2014 Congressional Research Service report—whose crimes are old enough to be grandfathered in. That select club includes spy-for-Israel Jonathan Pollard whose recent release, as I discussed last week, was only made possible because his crimes were committed before November 1, 1987. Last fiscal year, there were only 1,334 federal offenders on parole, according to a Government Accounting Office report. Total. The number of federal prisoners on parole or eligible for it, according to the GAO, plummeted by 67 percent between fiscal years 2002 and 2014.

“Mandatory minimum sentencing laws, the elimination of parole, and other policy choices helped drive this growth, which cost taxpayers an estimated $2.7 billion in 2012 alone,” the Pew report concludes. “Despite these expenditures, research shows that longer prison terms have had little or no effect as a crime prevention strategy—a finding supported by data showing that policymakers have safely reduced sentences for thousands of federal offenders in recent years.”

And so Bernie Sanders’ proposal to reinstate federal parole, if enacted, would be huge. If parole were to be reinstated, most federal prisoners would be eligible, according to a Congressional Research Service report.

“Data from the BOP indicate that nearly three-quarters of inmates have served at least 25 percent of their sentence, meaning that if Congress reinstated the old parole eligibility rules, a majority of federal inmates would be eligible for parole consideration,” the report finds.

And so: Why has this gotten so little attention? For one, criminal justice reform activism is understandably focused on police shootings, the most high-profile and spectacular form of domestic state violence. But reducing sentences is a key measure required to end mass incarceration, however mundane it might seem to be as a political cause. At the same time, parole can also be a potentially explosive issue for opponents of criminal justice reform: just one early-released prisoner who commits a heinous crime is enough to change the course of an election.

It was in 1988 when allies of George H.W. Bush released his infamous and racially-loaded Willie Horton ad, attacking Michael Dukakis for his state government letting Horton, serving life for murder, out on a weekend furlough—an opportunity he allegedly took to abscond and commit a gruesome rape and assault.

Nationwide, parole was eliminated or severely limited during the tough-on-crime era, and once-standard sentence commutations became politically-fraught rarities.

“Fourteen states and the federal government eliminated or severely restricted parole,” according to a Marshall Project investigation. “Boards that retained the ability to release people, meanwhile, became increasingly reluctant to do so.”

In Pennsylvania, Reginald McFadden’s life sentence for murder was commuted by Democratic Gov. Bob Casey in 1994. Shortly thereafter, he murdered two and brutally raped a third. Lt. Gov. Mark Singel was running to replace Casey. But Singel had presided over the Board of Pardons vote, and he had voted yes. Crime, and the release of dangerous criminals, dominated the campaign. Republican Tom Ridge won and quickly pushed through tough-on-crime measures. Commutations basically ground to a halt.

In 1995, the Pennsylvania Board of Probation and Parole paroled Robert “Mudman” Simon, a member of the Warlocks bike gang, who soon thereafter shot and killed a New Jersey police officer. The number of state prisoners paroled declined significantly. The only people who may have hated Mudman and McFadden more than the general public were his fellow prisoners who, on account of the two men’s horrible behavior, lost a shot at parole and, in the case of lifers, ever getting out of prison at all.

Pennsylvania’s prison population rose from 23,405 in 1991 to 51,638 in 2011, according to the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Last year, roughly 5,263 prisoners were serving life sentences in the state, just slightly more than the entire state prison population in 1968.

Reestablishing federal parole might still make many politicians nervous. For one, Hillary Clinton, whose campaign did not respond to requests for comment, does not include such a proposal in her criminal justice reform platform. She does, however, embrace the call to “end the privatization of prisons.” Probably, because that’s politically easier, and, as Sanders clearly understands, a more attractive soundbite.

Private prisons are no doubt objectionable. There is something rather unseemly about businesses making a profit from caging human beings, and it creates a dangerous political constituency with a business interest in protecting the status quo and fighting off efforts to end mass incarceration. There are not only private prisons but also companies that profit from imprisonment, like those that run price-gouging prison phone services, monitor people on probation and collect court debt. It would no doubt be a big deal if private prisons were abolished.

But in reality, private prisons housed just over 8-percent of all prisoners at the end of last year, according to Bureau of Justice Statistics data, though that includes a significant 19-percent of federal prisoners. Mass incarceration was built by the public sector, thanks to racist political sentiment, rising public fear of rising crime and many other complex factors. Closing private prisons is not enough because moving prisoners from private to public facilities will do little to nothing to dramatically reduce this country’s prison population.

The concept of the prison-industrial complex is seductive to many on the left because it corresponds to the idea that many bad things happen because of ruthless profit seeking. But mass incarceration remains at its core a public sector problem created by politicians. And political reforms, like Sanders’ proposal to reinstate parole, are the only way to end it.