This week, the Tax Policy Center examined Jeb Bush’s tax plan and found that it would increase the deficit by $8.1 trillion in the first 10 years. Earlier this year, Donald Trump released a new tax plan that included, among other proposals, cutting the top tax rate to 25 percent, cutting taxes on capital gains, reducing corporate taxes and entirely ending the estate tax. Though the plan was initially described as “populist,” later analysis suggests it is anything but. Other Republican plans have been similarly regressive, including Marco Rubio’s. Why can’t the GOP propose a plan that’s actually populist? My analysis suggests it’s because the donor class is disproportionately influential.

To see, I examined in depth how views between Republican voters and Republican donors are divided. In addition, I compared how nonvoters who are Republican differ from those who aren’t. I used the American National Elections Studies 2012 dataset, and examined three groups: individuals who donated to a Republican candidate, those who voted for Romney but did not donate and those who say they are or lean Republican, but didn’t vote. I examine the four questions in ANES that are most relevant to the tax policy debate. (All questions ask whether the individual is in favor of, opposed to, or neither favors nor opposes the policy in question.)

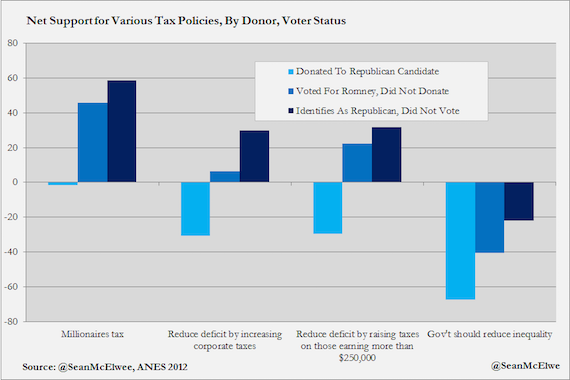

First, I examined support for a millionaires tax. Second, I examined two questions in the budget deficit section: whether individuals would support raising taxes on corporations and individuals earning more than $250,000 to reduce the deficit. Finally, I examined a question regarding inequality: whether individuals supported the government taking action to reduce inequality. The charts below show net support on each issue, meaning I subtracted the number opposed from the number in support.

As the first chart shows, there is a deep divide between the Republican donor class and other Republicans. It suggests that those who are inclined toward Republicans but don’t vote are also more likely than voters to accept higher taxes. The divides are stark, with donors on net opposing a millionaires tax (38 percent in favor, 40 percent opposed) but huge support among voters (65 percent in favor, 19 percent against) and nonvoters who lean Republican (70 percent in favor, 11 percent against). While Republican donors, voters and nonvoters are all skeptical of government intervention to reduce inequality, donors are far more skeptical (net opposition of 67 points, with 9 percent in favor and 76 percent opposed) than voters (net opposition of 41 points, with 17 percent in favor and 60 percent opposed) and nonvoters (net opposition of 22 points, with 22 percent in favor and 44 percent opposed).

To show the data another way, the chart below shows the percent of each group in favor of each policy proposal, and includes the percentage of all American in support. In each case the nonvoting Republicans are most in line with the general public, followed closely by Republican voters. But Republican donors are dramatically out of line with the general population. Less than a third of donors support decreasing the deficit by raising corporate taxes or taxes on those earning more than $250,000, but more than half of voters and nonvoters support the latter (as well as 68 percent of the general population).

These numbers show that Republican voters and nonvoters are also broadly in line, though obviously more conservative, than the general public on tax-related issues. As I’ve argued in my recent report, “Why Voting Matters,” voter turnout would force both parties to push for policies more in line with the preferences of average Americans. In this case, by making Republicans choose between their seat and the donor class, it may well reduce polarization and force a deal.

As Jonathan Chait noted when Trump’s plan was released,

“Actually running on a populist tax plan in a Republican primary has the benefit of appealing to a popular position, but at the cost of making Republican power brokers apoplectic, whereas merely pretending to have a populist plan has most of the same benefits and none of the costs.”

Jeb, who is closer to the donor class than any other candidate, has given them a plan that suits their preferences and interests. Republican voters are in favor of reducing the deficit by increasing taxes on the wealthy and on corporations. They also overwhelmingly favor a tax on millionaires. The problem is that those millionaires are running their party.