Imagine yourself in a bland hotel room anywhere in the United States. You’re sitting on the edge of a bed with tightly tucked white sheets, flipping through TV channels without finding anything you can bear to watch. Out of lonely boredom, you open the top drawer of the nightstand. Instead of the requisite King James Bible, you find an English translation of the Quran inviting you to read its pages: “This is a message to all people, to whomever among you desire to take a straight path” (81:27–8).

Americans applauding Trump’s promise to ban all Muslims from U.S. borders might imagine the scenario above as a foreboding future brought on by the “browning of America” and a Muslim fifth column’s “Sharia creep.” Rather than as a sign of the destruction of America, painter Sandow Birk imagined this chance, cross-cultural encounter with the Quran as the conceptual launch of his nine-year journey of reading and reflecting on the Islamic scripture and the War on Terror. The result is his "American Qur’an," an illuminated manuscript published by W.W. Norton as a stunning coffee table art book, ideal as a Christmas or Hanukkah gift, perhaps for a friend or relative on your list persuaded by the fear-mongering of Donald Trump, who claims simply, “We have no choice.”

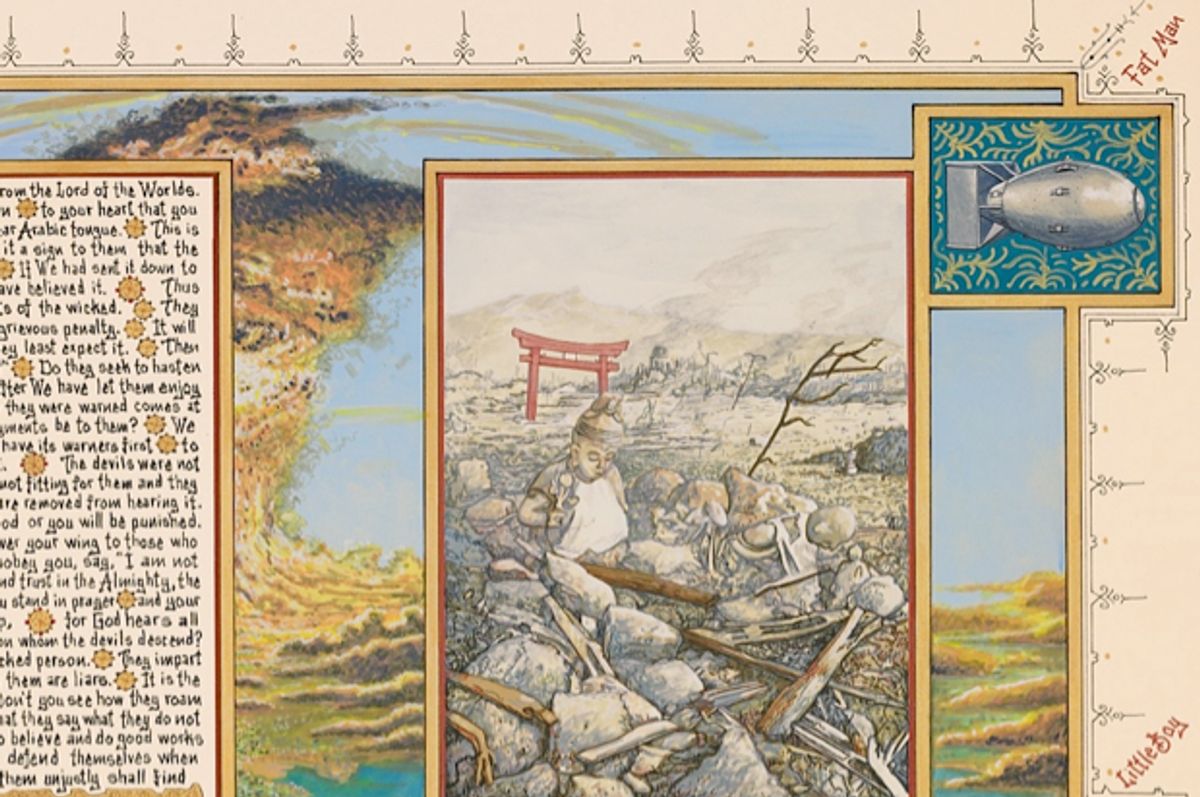

Birk’s "American Qur’an" intends to introduce the text to American audiences but he is neither inviting his readers to convert to Islam nor illustrating the history of Islam’s founding; the Quran struck him as far too poetic and abstract for such a literal approach. Birk eschewed the irony and satire that have become the knee-jerk impulse of so many Western artists who criticize the specter of Islam by representing the Prophet Muhammad as ugly, bloodthirsty, perverse and savage. In fact, Birk is unflinchingly neutral on the question of the reform of Islam. Contemplative and open-ended, Birk’s paintings collectively comprise a complete English transcription of the Quran bordered by narrative scenes of everyday life in the contemporary United States. In “Smoke,” Birk depicts the World Trade Center on Sept. 11 from the terrified pedestrians’ point of view. He critiques al-Qaida’s terrorism but also challenges the notion that contemporary Muslim political behavior was created and petrified in the seventh century text by analyzing contemporary jihadists alongside extreme forms of taken for granted state violence such as torture, capital punishment, warfare. Birk wants to provoke discussions, not riots, and while "American Qur’an" will likely strike many as controversial, his paintings reveal a welcome depth and seriousness lacking in so much of our national discourse about Islam.

Birk’s illuminated Quran is the first of its kind, not only because it is in English and its scenes are peopled, but also because Birk is not Muslim. For centuries, Muslim artists have created illuminated manuscripts of their sacred text out of faithful devotion. Birk’s relationship to the Quran is characterized by respect but not necessarily veneration. For example, Muslim artists have generally eschewed the human form in art that is explicitly religious and devotional in order to avoid graven images; Birk does not play by such Muslim rules. (Importantly, his paintings never received any Muslim backlash in the form of threats of violence despite years of media publicity and gallery shows.) Birk makes the Quran itself into a cultural criticism tool, a mirror, by making the exotic familiar and the familiar exotic, scrutinizing the beliefs and behaviors of ordinary Americans in much the same way as they typically scrutinize Muslim societies. Birk takes readers to each of the 50 states but also to places beyond the nation’s borders where the U.S. government exerts its power and force, often brutally: landscapes devastated by war in Japan and Iraq, the Guantánamo Bay prison camp in Cuba, and the militarized U.S.–Mexico border. Politically and artistically, Birk is quietly transgressive, and "American Qur’an" is far more interesting and edgy than the formulaic satirical depictions of the Prophet Muhammad that grab headlines.

Birk is driven by a political dilemma that troubles him and could not be more timely: Why can’t Islam be an American religion? Seventy-six percent of Republicans and 43 percent of Democrats polled believe Islam is incompatible with the American way of life. If the Bible, a 2,000-year-old book from the Middle East, is embraced as the very essence of American national culture and identity, why is another 1,400-year-old book from the Middle East deemed incomprehensible, dangerous and irredeemably un-American by so many? Birk’s "American Qur’an" tests both Islam’s claims to universality and the universal citizenship promised by American democracy. Can a white man who is not Muslim accept the Quran’s invitation to read, reflect on and interpret its verses without being accused of cultural trespass? Does the Quran have anything to say to a 21st-century American? Birk’s pairing of an image of a foreclosed house with the chapter titled “The Cheaters” is an emphatic affirmative answer to that question: “Woe to the cheaters, who demand full measure when they take from others, but short them when they measure for them” (83:1–3). As for whether there is room for Muslims in America, Birk suggests that we cannot know who is or is not Muslim just by looking at the people who populate "American Qur’an"; the same holds true for the people who populate America.

In the wake of the gut-wrenching San Bernardino, California, shootings, anti-Muslim discrimination and hate crimes have spiked though they were already on the rise. American Muslims are suffering a backlash and I am painfully aware that my non-Arabic name and unconcealed hair make me less vulnerable than friends and family who “look Muslim.” It is exhausting, frightening and alienating living among so many people who are ready to indict not only my faith but to punish me and millions of Muslims like me for the crimes of a few, crimes that I find just as terrifying as they do.

Growing up in Detroit, my family’s Quran was a cheap, worn paperback that belonged to my maternal grandmother, brought to the U.S. by my mother 40 years ago. The family lore about my grandmother’s short life was a spare mix of sad and inspiring fragments. As a young woman, she lost two of her daughters and their family farm to the war in India before she made a new life as a refugee in Pakistan. In her 50s, and with a greater semblance of peace, she nurtured a new ambition: to learn to read. There was only one book that she wanted to read, and she wanted to read it in its original language, not her native Punjabi. That book was the Quran. So she learned to read Arabic, a language she did not speak or understand, from a tutor, a young girl who had committed the entire book to memory. One page at a time, she worked her way through the book and it was her proudest and final achievement.

As a child, I learned to read Arabic the same way my grandmother did, phonetically, with only a vague sense of what the words meant. While I made my way through children’s primers with large blocky print, my grandmother’s Quran sat on a high shelf, wrapped in a neon pink stretchy material that reminded me of a bathing suit, complete with a single, long spaghetti strap my mother untied when she found a few spare minutes to read to herself. I felt the visceral power of the Quran’s words not in their translated meaning but in their ability to absorb my mother’s attention in a way nothing else could. Sometimes I would call her and she would not hear me, lost in fine black Arabic letters curling across thin, mint green paper.

That’s not to say I grew up in a strict, religious family. My mother taught piety by her example, not lectures. My family practiced Islamic rituals loosely and debated theology hotly. Fatwas were treated for what they were, mere religious opinions that one could take or leave, as numerous and varied as the guests at our dinner table arguing over them. Then one day an old turbaned man on television transformed the word "fatwa" into a license to kill. The world turned upside down over a novel that posited that the real author of the Quran was Satan. My teacher told our class the problem was that Muslims did not understand fiction as an art. He did not seem to understand that art could also be a racial insult. I did not say anything in class or to the teenage boys who called my Muslim friend a fundamentalist and threatened her with a knife at the bus stop. I wanted to share the Islam I knew intimately but all that stumbled out of my mouth was an embarrassed confession that my grandfather bore a striking resemblance to the Ayatollah Khomeini.

Now, as an adult and an Ivy League religion professor, I am far more prepared to field questions about Islam and the so-called clash of civilizations from friends and strangers, students and journalists. Many want me to disown the violence of jihadists as impurities polluting Islam’s peaceful essence; I disappoint them when I explain that interpreting the Quran incorrectly is not enough to put someone beyond the pale of the faith. Others want me to confirm that no institution has caused more bloodshed than religion and that a world without religion would be a peaceful one; I remind them that the 20th century may have been the most violent in history, with its world wars, colonial conquests, revolutions and counterrevolutions—much of the blood spilled in the name of nation-states, and not God. Others want to separate the ugliness of religion from a beautiful set of shared values that they call spirituality. They want me to confirm that Muslims believe in peace, compassion, forgiveness, generosity, and that once we boil religions down to their spiritual “essence,” we are all the same. They are surprised when I challenge the invisible line they have drawn between this thing they call spirituality and this thing they call religion. What if the rules and the martyrdom and the glorified suffering and the desire for power and the regimes of self-discipline blur right into the love and the light? Aren’t we surrounded by secular forms of all of the things we love and hate about religion?

Birk’s transcribed pages force us to confront our fears about how different and similar we might be. Some are frightened by Islam because even “moderate Muslims” believe the Quran is “the literal word of God.” When many Americans hear the expression “the literal word of God,” they misunderstand it to mean that Muslims only read the Quran literally or are only allowed to do so. In fact, a literal reading of the seventh verse of chapter 3 reveals that the Quran contains verses that are self-evident in meaning, as well as allegorical passages and mysteries beyond the comprehension of the human intellect. “[God] has sent down the Book for you. Some of its signs are decisive—they are the basis of the Book—and others allegorical” (3:7). Since the Quran never specifies which verses to take literally or allegorically, Muslims must rely on their communities of interpretation, often led by religious scholars such as jurists and theologians. Muslims have always argued over the Quran’s meanings. After the Prophet Muhammad’s death, an early community of Muslims challenged what they saw as the excessive interpretive liberties of the Caliph Ali, the Prophet's cousin. They accused the caliph, in his capacity as ruler, of trespassing over the bounds of human interpretation and encroaching on the dominion of God’s law. In response, Caliph Ali brought a Quran to a large crowd. Touching the book, he instructed it to speak and to explain God’s law. Alarmed and surprised, the onlookers protested, “The Quran cannot speak, for it is not human!" This, the caliph explained, was precisely his point. As mere ink and paper, the Quran does not speak for itself. It is human beings who give the book its consequence by reading, reflecting, drawing out meanings and lessons, constructing arguments, all contingent on their recognition of the inevitable limits of human understanding and the limitlessness of the book’s divine truth.

Birk remains unconvinced of any claims of divinity; however, he is seeking answers to big questions. Why are we here? What happens after we die? Why do bad things happen to good people? By virtue of its format, with text boxes partially obscuring scenes, Birk forces us to confront our own biases. In forcing us to try (metaphorically) to peer around the Quran’s words to see what is happening in his scenes, Birk highlights our always partial (in both senses of the word) understanding. His "American Qur’an" teaches us to look with humility, to remember that none of us has a God’s-eye view of our world.

Imagine that the English translation of the Quran you discovered in the top drawer of that hotel nightstand or under your Christmas tree was Sandow Birk’s "American Qur’an."

Shares