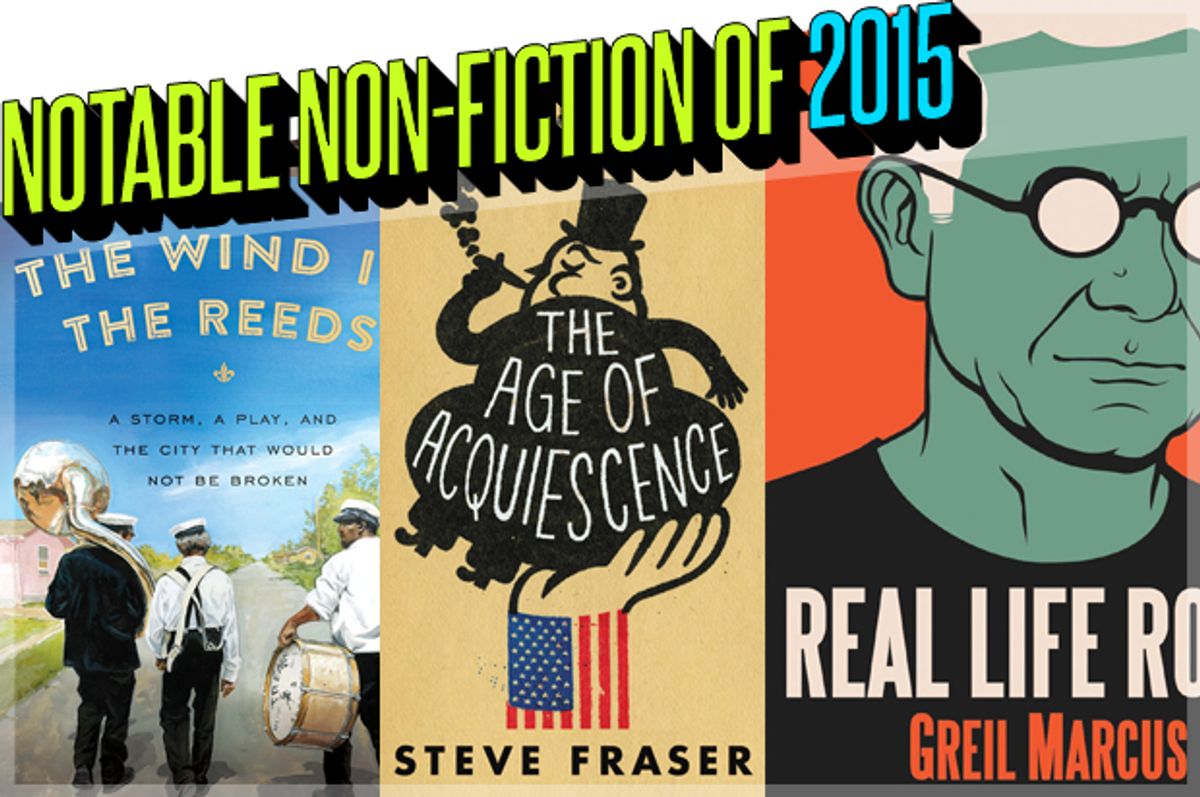

Te-Nehisi Coates’ “Between the World and Me” drew a huge amount of praise and controversy this year, and music memoirs by Carrie Brownstein, Elvis Costello and Patti Smith broke out as well. But nonfiction in 2015 was rich and wide, and asked a huge range of questions. What is the Internet doing to our ability to connect to each other? How did terrorist action shape the work of William Shakespeare? Why do celebrities keep telling us what to do and what to eat? I’ve not read every nonfiction book of the year, but here (alphabetical by author) are 10 idea-driven books that make their cases persuasively and accessibly.

"SPQR: A History of Ancient Rome" by Mary Beard

Beard is an intellectual celebrity in Britain who has broken out in the United States thanks to this engaging and awkwardly titled history. She writes about Rome from top to bottom, looking at Cicero and Augustus as well as slaves and women. Rome, she argues, gave us much of our contemporary ideas of citizenship. She’s worth reading for the bite of her prose alone.

"Is Gwyneth Paltrow Wrong About Everything?: How the Famous Sell Us Elixirs of Health, Beauty & Happiness" by Timothy Caulfield

An odd hybrid of gonzo first-person journalism, celebrity obsession and serious medical research, this book by a scholar at the University of Alberta considers claims made by famous people and their enablers in the media and the fringes of medicine. Solidly grounded in science and often hilarious, Caulfield’s book asks, What do these celebrity claims – and the whole worship of wealthy and beauty – do to us and our society?

"The Age of Acquiescence: The Life and Death of American Resistance to Organized Wealth and Power" by Steve Fraser

Besides very focused, and temporary, outbreaks of energy like the Occupy Movement, our era has seen most of us rolling for a new plutocracy, argues labor historian Steve Fraser in this forceful and at times wryly funny book. Compared to the 19th century’s Gilded Age, we’re sleepwalking; back then, a suspicion of the way unbridled capitalism distributed the spoils was widespread, across class and region.

"Love Songs: The Hidden History" by Ted Gioia

Known mostly for his books on jazz and the blues, the music historian goes back thousands of years, looking at an enormous range of love songs: Mesopotamian fertility rites, Sappho, opera, Frank Sinatra, punk rock and “American Idol.” Gioia finds that the love song has been assailed over the centuries, but has survived and reinvented itself. He also finds that some aspects of the love song -- and of the West’s notion of romantic love -- originate in the Muslim world. (Disclosure: Gioia is a friend. But “Love Songs” is so good I could not leave it off.)

"The Art of Memoir" by Mary Karr

All books about writing give a sense of the author’s taste. But “The Art of Memoir” is so ecstatic about Karr’s favorite books that it serves as a guide to reading as surely as it does to writing. Her descriptions of Vladimir Nabokov’s “Speak, Memory” are especially strong. Throughout, the book is as ornery and opinionated as Karr’s own memoirs.

"Real Life Rock: The Complete Top Ten Columns, 1986-2014" by Greil Marcus

Marcus is best known for making long, counterintuitive arguments about the way music, culture and politics overlap. But here he is in bite-size pieces driven by his passions for individual bands (TV on the Radio, the Mekons, Sleater-Kinney), an ad, a movie, an author or an art exhibit. You don’t get a sustained idea, but you do get Marcus’ eclecticism and ability to make quick connections. For most readers this collection of columns from the Believer, Salon and elsewhere is best read a small bit at a time. The book is only marred by his refusal to acknowledge the genius of Lucinda Williams.

"The Wind in the Reeds: A Storm, a Play, and the City That Would Not Be Broken" by Wendell Pierce

Samuel Beckett’s plays are rarely seen as beacons of hope. But Wendell Pierce, best known as an actor in “The Wire,” helped put on “Waiting for Godot” as a way to reinvigorate his hometown, New Orleans, after it was nearly washed away by Hurricane Katrina. This is not a celebrity memoir but a gracefully written book about a city’s history, an actor’s respect for his craft, and an idea that turns out not to be outdated, after all: the power of theater.

"The Year of Lear: Shakespeare in 1606" by James Shapiro

Shapiro’s vivid, richly detailed book looks at the way Catholic-Protestant tensions and a failed attack on the House of Lords shaped Shakespeare’s “King Lear,” “Macbeth” and “Antony and Cleopatra.” Shapiro is hardly the first to connect the playwright to politics and history, but he makes the story gripping.

"Reclaiming Conversation: The Power of Talk in a Digital Age" by Sherry Turkle

Turkle, an MIT psychologist, has been one of the sharpest observers of the Internet’s effect on our social lives for years now; her book “Alone Together” is a landmark. “Reclaiming Conversation” looks at the value of face-to-face connection and considers in great detail what happens to our social lives, our society, even our individual psyches, when digital devices get in the way.

"The Shifts and the Shocks: What We’ve Learned – and Have Still to Learn – From the Financial Crisis" by Martin Wolf

Wolf, an editor and commentator at the Financial Times, writes with anger and bitterness about how banks and governments failed to fix the mess of the Great Recession. A onetime anti-Communist and supporter of market-based solutions, Wolf has come to see that “faith in unfettered financial markets” can become deadly.

Shares