In mid-December, Omnivore Records announced a reissue of Game Theory's 1987 double LP, "Lolita Nation." To say the news was long-awaited is an understatement: The album has been out of print and nearly impossible to find on CD for many years (unless you want to shell out big bucks on eBay), and it's considered by many to be the finest work produced by songwriter Scott Miller. Although known as a power-pop touchstone, the Mitch Easter-produced "Lolita Nation" is actually far denser and more complicated than that tag might imply: The collection leapfrogs through genres and sounds—theatrical synthrock, psych-torqued pop, swaggering jangle-rock, British Invasion exuberance, soul-jazz moodpieces—with fluid grace and ease.

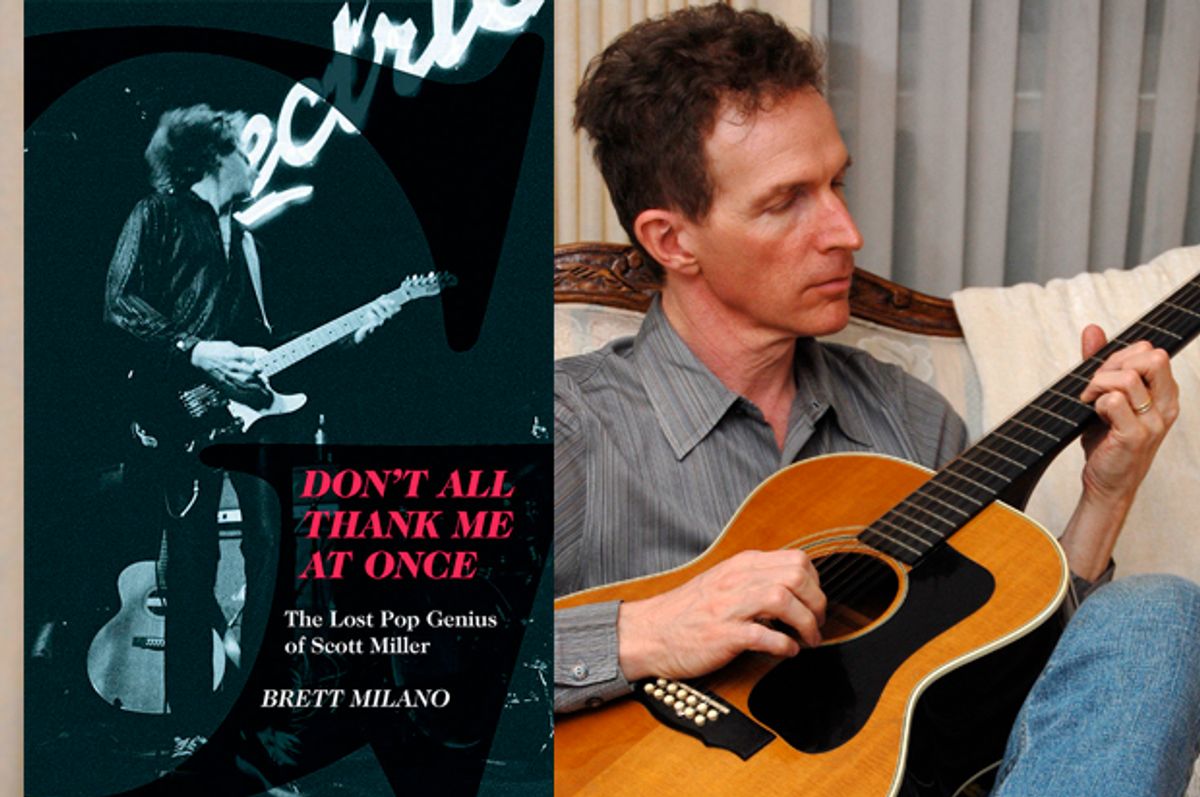

One of the more bittersweet aspects of the "Lolita Nation" reissue is that Miller isn't here to see it, as he took his own life in 2013. His unexpected death stunned fans, and spurred an outpouring of grief and admiration from musicians, journalists and fans alike. One such admirer was Boston-based journalist Brett Milano, who recently published a compelling, comprehensive biography of the musician, "Don't All Thank Me at Once: The Lost Pop Genius of Scott Miller." (More information and places to buy the book are here.)

Milano—a long-time fan of Game Theory and Miller's other band, the Loud Family—dates his fandom to hearing the former band's song "Here It Is Tomorrow" on the radio. "It was like, 'Oh my God, the way [Miller] hit you over the head with that hook,'" Milano recalls. "He keyed into a real exhilaration which at that time I was not feeling from enough music. He just made me remember that if somebody turns a hook a certain way, it can change the entire quality of your life for a few moments."

In "Don't All Thank Me at Once," Milano amplifies and explains those moments of exuberance via detailed analysis of the Game Theory and the Loud Family catalog, courtesy of interviews with band members and others around the group at the time. He weaves these tales into the story of Miller's life—how he grew from a teenage music fanatic into someone who, in the last decade, had nearly left music behind after becoming a father. The book also delves into the fact that Miller was in the early stages of working on a new Game Theory record when he passed, which would've been the first LP from that group since 1988. (This album is being completed by a slew of talented musicians and released under the name "I Love You All" in 2016.)

Milano started thinking about writing "Don't All Thank Me at Once" after Miller died. "A lot of us that knew him and knew his work were affected by that, and thought it was a bit of a crime that he had never really been recognized," he says. "The quality of his work was way out of sync with the amount of recognition he got." Milano decided to put together a proposal for the 33 1/3 series of books on "Lolita Nation," which he knew was going to be reissued. That ultimately wasn't successful, but he says he received enough encouragement.

"What the [33 1/3 series] editor finally said was, 'This is a little too non-commercial for us, but I love this proposal,' which I took as my cue to go a little further with it," Milano says. "I decided, 'Let's try and make this a real proper biography, and try to get a handle on who Scott was and how that played into the music he made. Let's get into his entire body of work.' A bunch of interviews later, that's where it wound up."

Milano spoke with Salon about the genesis and execution of "Don't All Thank Me at Once," as well as Miller's music and legacy.

What unique challenges did the book pose for you?

Well, it was my first foray into telling a personal story, not just talking about somebody's music. And in this case, you had somebody that isn't with us anymore. So I had to get as much of a handle on what his life had been as I could, which means that not just talking to people that he played with. I tried to talk to people that were important and intimate in his life, which wound up including his mother, who is 93, who I wasn't sure I'd ever get a chance to talk to, and his wife, his widow, who obviously was still quite bereaved. Her being willing to open up about things was a big help.

When you're writing a book about someone who isn't there anymore, the emotions are on the surface. I was really impressed how many people were willing to talk about him.

More than a couple of people became very teary when I interviewed them. His memory was very fresh to them. If Scott didn't feel that people really cared about him deeply, he should've heard some of the interviews I did.

You hate to hear that stuff now. It's kind of like with the reissue campaign—the "Lolita Nation" trailer came out this week. It's so exciting, and it's such a shame it took him passing to get all this stuff in motion.

That's the horrible, sad part. But on the other hand, it didn't have to go that way. One thing you can see in the book is he was planning to make another record, which would've come out under the name Game Theory. The deal to reissue the albums—it had not come to fruition in his lifetime, but it was already on the table anyway. So I think the end of the story could've been quite different, if he could've finished the record he was intending to make and have that come out around the same time as the "Lolita" reissue. I don't know if he would've ever gotten quite the stardom he deserved, but he certainly would've been a little more enshrined in the ranks of cult heroes who need to be paid attention to.

But the book wasn't sad. It was humorous at times, and it brought to life why his music was so compelling and smart.

To me, he wasn't "insert the name of somebody whose music is invariably depressing." He wasn't one of those people. I find a whole lot of joy in his music, and a whole lot of life-affirming stuff. My personal favorite album is "Plants and Birds and Rocks and Things," the first Loud Family album, which does include some incredibly despairing songs. But on the other hand, there's some songs that are completely exuberant and full of life. That's what Scott was all about. His music was really about absorbing your emotions and your psyche and your intellect into everything that there is to be found.

Which I think is important. There's a whole mythology when a musician passes away before he should or before his time—people tend to focus on the melancholy or the warning signs. But I listen back to so much of his music now, and it's like, "Why wasn't this a hit? This is wonderful." It's so upbeat; it's so smart. It's complicated and dense, in a really wonderful way.

Exactly. And it was never complicated and dense in a way that people wouldn't get. And I don't really think you can say, "Oh yeah, makes sense that people wouldn't listen to this, it's so out there." It never really was. Probably the biggest stumbling block people ever had with him is that he had a higher voice. But certainly by the time you get to the Loud Family, he was singing in a much different register, and it was a classic model pop voice. It was not one of those voices that would not have sounded good on the radio.

And now, there's dozens of indie rockers who sing in a similar high register!

I know! [Laughs.] You hear a record like "Plants and Birds and Rocks and Things" and it's like, "Where were all the Weezer fans when this record came out?" They would've heard the same qualities in this.

You were a huge Scott Miller fan for many years. What did you learn about him as a musician or a person from doing this book?

There were some things I took that were true about him already. I actually worked with him somewhat, because I was at the Alias label when he was submitting "Plants and Birds," and he would send track lists to us before the songs were even recorded and may not have even been written. Fully conceptualized track lists, ideas for what the cover was going to look like. I definitely got it that he was one of those people that comes up with fully formed, incredibly complex ideas in his head. The whole idea of him being a brainiac was pretty much true.

And I also figured out that he was pretty emotionally complex. It turned out to be even moreso than I had imagined, because even his closest friends did not really fathom what was going on in his head. Even his family really didn't have an inkling of what was going on with him. I mean, why he took his life still puzzles and disturbs a whole lot of people. He was really good at holding things close to his chest, which is tragic. But I did not quite realize how advanced he was in terms of that.

Throughout the book, there is a thread that he is enigmatic, and you don’t really know him. But it's almost like people didn't realize how much they didn't know him until he passed. That stood out to me when you read some of the quotes people gave, and their observations.

He was famously self-deprecating, and he was self-deprecating in a really funny way, particularly about his lack of success. But I don't think people realized that maybe there was a lot of actual pain behind that self-deprecation. I do think he felt the rejection, I think, that his records weren't doing better than they were.

You wish you had another day to ask him.

I still have Facebook messages from him in my inbox. And one time, I was reading over the online column that he did, "Ask Scott," and I was looking at his answer to a question, and I thought, "Well, this is really nice he framed it this way." And then I saw that I had actually asked the question. [Laughs.] Here's Scott here and now, guiding me along, answering a question for this book. It's like, "Wow."

As much of a mastermind as he is, it bore out to me that the music was really a product of a lot of other people as well. It brought some of the life back to that music to reconnect with people like [Game Theory drummer] Gil Ray and [Game Theory guitarist/vocalist] Donette Thayer, [Loud Family guitarist] Zachary Smith and all the people that were collaborators and parts of his vision in those different bands.

And the book was as much an analysis of the music as it was about Scott.

That's why we care about this guy, really, is that he was so good at doing this. We can't quite understand what made him so good at doing this, but we can get a sense of how he approached it. He wrote a lot of his lyrics in a notebook on the train on the way to work, because he didn't drive. [It's like] "Okay, I've got an hour before I have to check in at the office; here comes a pop masterpiece."

When you started doing interviews with everyone in his life, did the book take any unexpected turns? Did your approach or the structure change at all depending on the answers and information you took in?

I was presented with some material I had to treat a bit sensitively. He did have a first marriage that fell apart. And then there was the issue of his death and how to present that, which I knew were going to be the hardest parts of the book. I knew that there would be a lot to balance in terms of my responsibilities as a biographer versus being a bit sensitive to the people involved. Those were the biggest challenges, having to absorb all the information around that and figure out what exactly to do with it. The way that Scott actually died, the specifics of that, I was asked not to present that. And because the information isn't actually public anywhere, I thought that the family was justified in having the call on that one.

His band members, fans and friends have been really protective of his family and legacy. People aren't being salacious about it; they've been really supportive. I think that speaks to the quality of the character of the people he had around him, and the character of his fans.

It really does. It says that he reached a lot of the people he wanted to reach, people that would think a little more deeply about the music they were listening to.

What makes Scott Miller compelling as a person and as a musician and as a book subject?

What makes him compelling as a musician is that his stuff did have all these allusions and all this complexity to it, and yet it was Beatles-level catchy. You hear these songs—whatever makes you fall in love with a pop song and have this glorious hook ringing inside of your head for days and days, he did that. What makes him interesting as a person is he was a real anomaly in terms of who made pop music. He wasn't into sex and drugs particularly. He was monogamous in his relationships. He had this ability on the road to go to events where the entire band was partying, drag a mattress in the middle of the floor, and fall asleep. He was somebody that was really purposeful and really single-minded about wanting to create music. He didn't get into it for any lifestyle reasons.

I think people relate to him, because he truly was a romantic. When he fell in love, he fell in love really deeply. He got really hurt by his relationships, and he got really exhilarated when the relationships worked out. [And] the template for a pop song is capturing that kind of thing. That's who he was. In a lot of ways, he was the kind of person that his music appealed to—people that were a bit more sensitive than the norm, and that had a bit more hunger for musical experiences than most people did.

When people read the book, what kind of takeaways do you want them to get from it?

"Oh my God, why didn't I listen to this guy? I'd better start right now!" [Laughs.] People have said they've cried after reading the book, which I didn't really intend that. I think for some people it was more of a healing thing to read it. It was to write it, for sure.

Shares