Republican legislators and candidates responding to President Obama’s recent executive measures on gun control have openly and willfully distorted the president’s stated policies and ambitions. Thus, when Paul Ryan says “the president has never respected the right to safe and legal gun ownership,” it’s not because his listening and reading comprehension are so poor that he took the following words from Obama’s speech to mean their diametric opposite:

Now, I want to be absolutely clear at the start—and I’ve said this over and over again, this also becomes routine, there is a ritual about this whole thing that I have to do—I believe in the Second Amendment. It’s there written on the paper. It guarantees a right to bear arms. No matter how many times people try to twist my words around—I taught constitutional law, I know a little about this—I get it. But I also believe that we can find ways to reduce gun violence consistent with the Second Amendment.

Nor do we have evidence that Obama’s words are empty, that he’s only verbalized support for the Second Amendment while taking contrary actions. In fact, the Obama presidency has been a resounding success for gun sales and production. So how are we to understand Ryan’s statement and like statements by Republican politicians?

Ryan, like many politicians on both sides of the aisle, is being cynical. True, it’s particularly disconcerting when someone exercises that kind of cynicism in response to a president crying for the dead—the dead schoolchildren, the dead churchgoers, the dead on the streets of Chicago—and all other varieties of gun-murdered citizens—but Ryan and the Republicans are hardly our only detached cynics. They are, however, our most open and brazen ones, particularly on the issue of modest gun-control measures of the sort that—it’s a cliché at this point to state—a vast majority of Americans and Republicans support.

It’s simple enough to haul out the conventional analysis, which is really no analysis at all: per Federalist 51, to paraphrase: men aren’t angels. The gun lobby backs self-interested politicians like Ryan who in turn look out for the gun lobby’s interests. As Obama said in his recent speech, “the reason Congress blocks laws is because they want to win elections”; and they win elections with the aid of gun lobby money, even by legislating against the will and best interests of the American people.

While I think this is true, I also think the cynical response to gun control is telling us something else about the state of conservative politics more broadly, something worth learning from. Between responses to gun violence and the rhetoric of the 2016 crop of Republican presidential candidates, it’s clear that cynicism is itself a prevailing conservative value, deeply important to the present iteration of conservative politics.

For a long time we were told that the rupture between “values” and “fiscal” conservatives was holding conservatism back. Untenable distinctions between “values voters” and Randian champions of the free market have only been complicated by free-market forces that reward presidential candidates' faux-populism with media and book deals, then sell those products to “Tea Party” conservatives who technically aren’t supposed to lionize the 1-percenters whose books they’re buying. Donald Trump, Ben Carson and Carly Fiorina are all excellent examples of how to cynically package oneself as a populist while favoring policies devastating to low-income Americans, then profiting from the bait-and-switch.

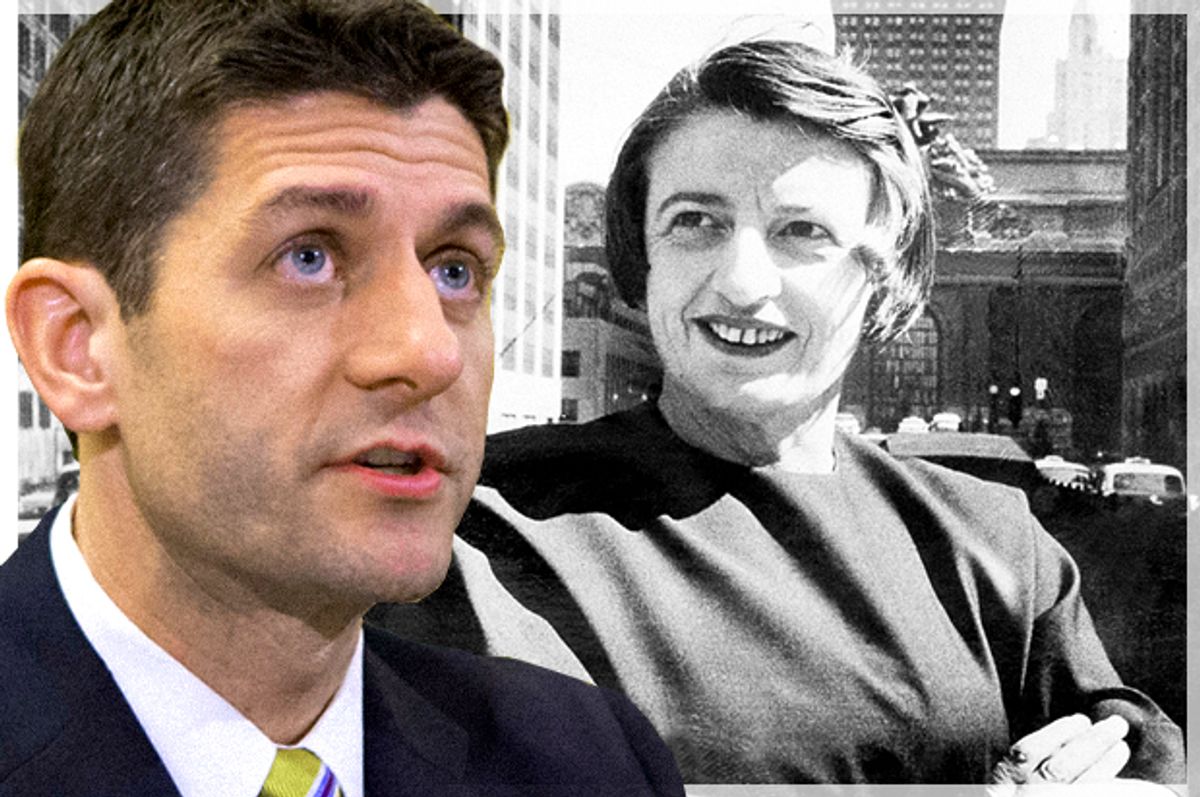

This is to suggest—hardly for the first time—that professional politics on the Republican side has become even more explicitly a training ground for cynics, political figures with low chances of election who are thriving in the shamefully lucrative business of American politics not after they’ve been elected and served in office (like the Clintons), but before. Meanwhile, those actually tasked to govern—like Paul Ryan, and John Boehner before him—are hamstrung by the kind of cynicism that, thanks in part to the show of cynicism and self-aggrandizement that the presidential candidates are putting on, conservative voters mistake for virtue.

If you prod a little, it becomes clear that cynicism is not merely at the root, but at the surface of conservative politics and policy. The conservative notion of freedom itself has become cynical. It’s no longer the libertarian credo “your freedom to swing ends where my nose begins,” but “if you can get away with it, do it.” If you can get reelected while backing the interests of the gun lobby above those of 90 percent of Americans (and those of the roughly 30,000 a year who die from gun suicide and gun murder), do it. If you can get reelected by making it more difficult for poor, young or minority citizens to vote, do it. If you can increase profits by keeping wages so low that taxpayers have to pick up food and healthcare expenses of the working Americans you employ, do it. If you can “monetize” public education at the expense of the most socioeconomically disadvantaged children, do it. And if you can scapegoat an entire world religion in the process to take the heat off yourself, do it.

Each of these positions is an example of cynicism as a values copout, a refusal to take a moral stand within a flawed system, be it an amoral “free market” or a compromised electoral process that quite possibly no longer constitutes democracy. “Economic” and “political” decisions quite obviously can’t be extricated from their moral import; it’s impossible to pretend that holding wages low is a business decision only, or that blocking a bill aimed at preventing terrorists from buying guns—in other words, “politics as usual”—has no moral implications. Yet cynicism of this sort is something we tolerate, even excuse, far too readily.

The distinction political analysts should pay more attention to, then, is not between “values” conservatives and “fiscal” conservatives, or the “Tea Party base” versus the “establishment.” Rather, we should differentiate—across parties, by all means—between the cynics and the people who have enough moral courage to set value boundaries beyond “what can I get away with?” Recourse to the laws of a market or an electoral system is not moral reasoning. Cynicism—“what can I get away with?”—is an insufficient morality. The price of cynicism on gun control has a dollar value, to be sure. Need we ask about the cost?

Shares